Quote of the Issue

“From Hayek’s perspective, a socialist economy could not realize its potential for innovation, since diverse entrepreneurs are not free to compete with one another for market share through new products and methods, diverse financiers are not free to bet on their private judgments in deciding which new ideas to back, and diverse creative types are not free to compete with one another for an entrepreneur to help develop their new ideas.” - Edmund S. Phelps, Mass Flourishing: How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge, and Change

The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised

“With groundbreaking ideas and sharp analysis, Pethokoukis provides a detailed roadmap to a fantastic future filled with incredible progress and prosperity that is both optimistic and realistic.”

The Essay

👽 What the '3 Body Problem' teaches about stagnation

Warning: This essay contains significant spoilers about The Three-Body Problem, the best-selling science-fiction novel by Cixon Liu, also now a Netflix series.

The mysterious Trisolaran aliens in The Three Body Problem want to invade Earth and seize the planet for themselves. The rub? Although Trisolarans are a much older civilization and far more advanced than Earth’s dominant species, humans are way better at generating continuous technological progress. (One likely reason: Trisolaris, a planet in the Alpha Centauri star system, has a catastrophically unstable climate that causes repeated collapses of the aliens’ civilization. They’re constantly starting over, while humanity — blessed by a comparatively stable climate — continues to advance.) By the time the Trisolaran warfleet completes its 400-year journey to Earth at one-hundredth the speed of light, humanity will have far eclipsed its tech capabilities. In the book, a Trisolaran scientist explains to its superior the harsh reality of its herky-jerky linear progress versus human exponential progress:

Let’s observe the facts: Humans took more than a hundred thousand Earth years to progress from the Hunter-Gatherer Age to the Agricultural Age. To get from the Agricultural Age to the Industrial Age took a few thousand Earth years. But to go from the Industrial Age to the Atomic Age took only two hundred Earth years. Thereafter, in only a few Earth decades, they entered the Information Age. This civilization possesses the terrifying ability to accelerate their progress. On Trisolaris, of the more than two hundred civilizations, including our own, none has ever experienced such accelerating development. The progress of science and technology in all Trisolaran civilizations has been at a constant or decelerating pace. In our world, each technology age requires approximately the same amount of time for steady, slow development.”

The princeps nodded. “The fact is that four million and five hundred thousand hours from now, when the Trisolaran Fleet has reached the Earth, that civilization’s technology level will have long surpassed ours, due to their accelerating development. The journey of the Trisolaran Fleet is long and arduous, and the fleet must pass through two interstellar dust belts. It’s very likely that only half of the ships will reach the Earth’s solar system, while the rest perish along the way. And then, the Trisolaran Fleet will be at the mercy of a much more powerful Earth civilization. This is not an expedition, but a funeral procession!”

The Trisolarans, however, have devised a solution: slow humanity down. To do this, they create and send two protons to Earth — as subatomic particles, the protons can move at light speed — which then unfold into two-dimensional forms to create Sophons. These are essentially quantum computers capable of incredible feats, including the ability to interfere with Earth's scientific experiments (such as cutting-physics conducted by particle accelerators), monitor all human communication in real time, and spread misinformation — all happening with some help of human collaborators who treat Trisolarans as divine.

Beyond direct interference in scientific progress, Trisolarans hope the mere knowledge of Sophons and their capabilities can demoralize scientists, policymakers, and the general public. Knowing that any technological breakthrough could be monitored or thwarted by Trisolarans will create a sense of futility and despair in humanity, potentially slowing innovation through a decrease in effort and investment in research and development. People will lose hope in science, specifically, and progress, generally.

The Trisolaran plan is so diabolically clever, it almost makes me wonder if the true explanation for America’s Great Downshift — the surprise slowdown in tech progress and productivity growth since the early 1970s that I write about in The Conservative Futurist — is, well, aliens! I mean, if there were a couple of Sophons bopping around the planet and messing with us, how would the results be any different than what we’ve experienced for the past half century?

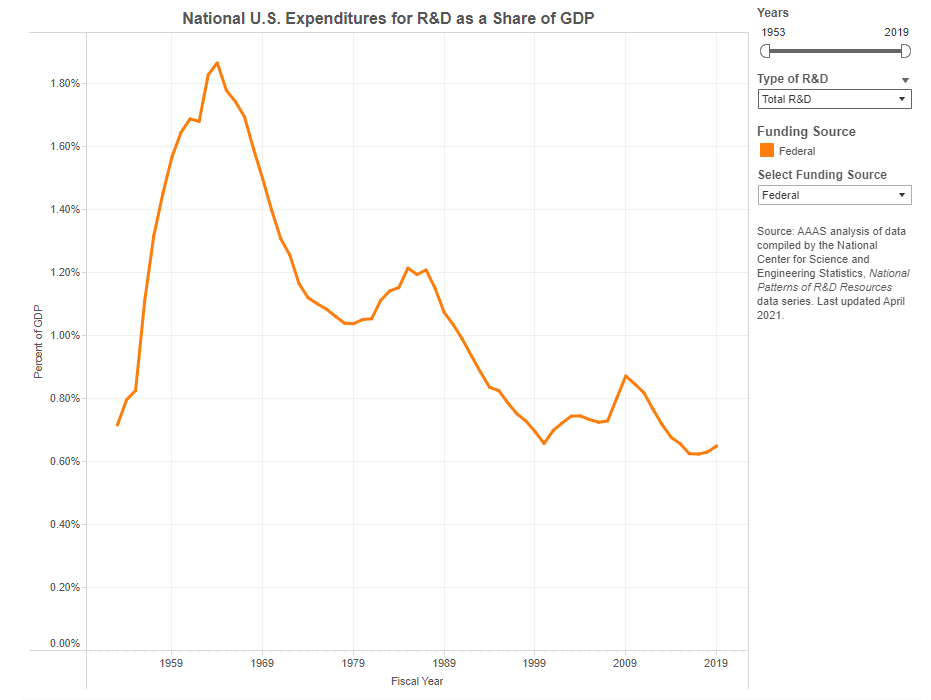

Think about it: Less frontier-pushing scientific effort? We can sure check that box. Federal R&D spending has declined by two-thirds as a share of GDP since 1964, according to the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

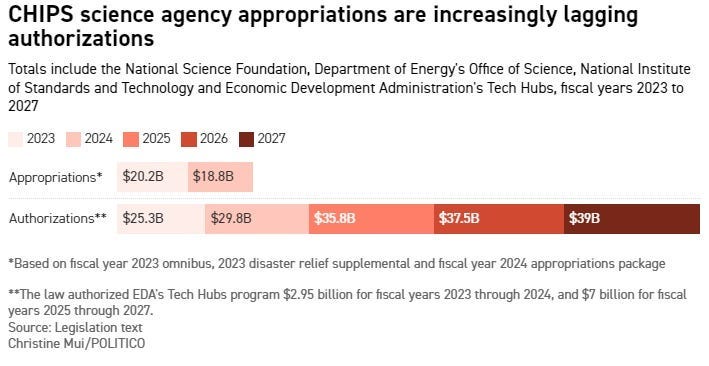

What’s more, perhaps these hypothetical aliens are right now continuing their dirty work and messing with our heads. That would sure explain how despite a) five decades of disappointing tech-driven productivity growth, b) the existence of a geopolitical competitor that wants to be the global tech and economic leader, and c) loads of research showing the growth impact of government science investment, Washington still won’t give a massive boost to R&D spending. The 2022 CHIPS and Science Act was supposed to provide a huge funding boost, but Congress has significantly underfunded key agencies and programs as intended.

As Politico reports:

While nearly $53 billion is going into reviving a homegrown semiconductor industry, Congress has gnawed away at the law’s ambitions on fundamental research and development aimed at staying ahead of China and other rivals in competitive fields like artificial intelligence. The latest example is the spending package lawmakers advanced over the past week: Biden’s signature enacts deep cuts to the National Science Foundation and stalls key offices in the Commerce and Energy departments that are supposed to deploy CHIPS money, turning a promised cash infusion of $200 billion over a decade into a humiliating haircut. And while it’s hardly the first time Congress has reneged on promised funds, it threatens an important pillar of Biden’s industrial policy. … The National Science Foundation offers a window onto the broader challenge, as the agency that expected to gain the most from CHIPS. The law authorized NSF to receive $81 billion over a five-year period that would ultimately double the agency’s budget by 2027. This year, the NSF should have gotten $15.64 billion, according to the CHIPS Act. Under the latest spending deal, lawmakers provided NSF with $9.06 billion — 42 percent short of the CHIPS target and an 8 percent cut to its current budget.

The Trisolarans are an impressive bunch, so it makes sense that some humans would be so dazzled that they would treat them as gods and be happy to do their bidding — including sabotaging their fellow humans. In our world, such a role is played by environmentalists and NIMBYs. These are folks who, over the past half century, have acted as Sophons in slowing tech progress.

For example: You can thank them for 1970s-era environmental regulations that make it maddeningly hard to build big projects in America, either quickly or cheaply. And you can thank them for continuing to use such regulations today. These are just a few of the headlines from the past month or so:

Tribes, environmental groups ask US court to block $10B energy transmission project in Arizona

Lawsuit challenges lithium project at California’s Salton Sea

More Sophons: Those in Hollywood who continue their public demoralization campaign about technology — AI will kill us, cancer cures will turn us into zombies — and the future. Next week, American moviegoers can watch the new film Civil War:

In the near future, a team of journalists travel across the United States during the rapidly escalating Second American Civil War that has engulfed the entire nation, between the American government, the separatist Western Forces of Texas and California, the Florida Alliance, and the New People's Army. The film documents the journalists struggling to survive during a time when the U.S. government has become a dystopian dictatorship and partisan extremist militias regularly commit war crimes

In my book, I highlight a study by Yale University economist Ray Fair that finds an interesting historical coincidence. First, US infrastructure spending as a percent of GDP began a steady decline around 1970, a pattern seen in no other rich country. (“The United States appears to be a special case in this regard,” Fair writes.) And at roughly the same time that America started ignoring its roads and bridges, Washington started running big budget deficits. As Fair sees it, the two trends provide evidence of a sustained change in national attitude: “The overall results suggest that the United States became less future-oriented beginning around 1970. This change has persisted.”

What’s more, Fair is “doubtful” the sustained shift can really be explained, not that he doesn’t float some possible explanations:

The years 1968, 1969, and 1970 had many noticeable events: the early baby boomers moving into their 20s; the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy; the beginning of the women’s movement; the draft, the bombing of Cambodia, and unrest on college campuses; Woodstock; Stonewall. Did any of these increase the impatience of the country in a permanent way? There are likely stories that could be woven, undoubtedly more than one, but it is unclear whether anything could be tested. The question is probably too big, but the fact is interesting.

In The Conservative Futurist, I float my own explanations for the Down Wing shift that underlay the Great Downshift in tech progress and growth. I try to explain why various macroeconomic headwinds (such as important breakthroughs requiring more resources than in the past) nor our policy mistakes (such as less R&D spending, more anti-growth regulation) provide a complete explanation of our current predicament.

From the book:

Yes, progress was harder than almost anyone imagined. But when progress failed to happen as expected, decade after decade—especially when it became clear our interventions weren’t working as well as hoped—why didn’t we work harder and smarter to make those Up Wing dreams come true anyway? Why did we let ourselves lose the future?

My answer is multi-causal:

The Vietnam War drove many, especially environmentalists and intellectuals, to see modern technology and large technological systems as inherently destructive forces.

Rising nuclear fears after WWII and incidents like the 1950s Castle Bravo test contaminating a Japanese fishing boat planted seeds of doubt about nuclear power and technological progress in general.

High-profile environmental disasters like the Santa Barbara oil spill and Cuyahoga River fire reinforced concerns about humans damaging the planet.

Influential books like Rachel Carson's Silent Spring and The Limits to Growth argued that unrestrained economic growth and technological development would lead to catastrophic pollution, resource depletion, and overpopulation.

The decline of optimistic Up Wing futurism in the 1960s, replaced by dystopian and apocalyptic visions in popular culture, deprived society of positive images of the future.

Sorry, it wasn’t aliens or Sophons. It was us.

Micro Reads

Business and Economics

Elon Musk Boosts AI Engineer Pay in ‘Craziest Talent War’ - WSJ

The Creativity Decline: Evidence from US Patents - St. louis Fed

Amazon's AI Stores Seemed Too Magical. And They Were. - Bberg Opinion

Chip Startup Raises $70 Million to Quicken AI on Cars and Robots - Bberg

The energy transition: Technology versus political backlash - VoxEU

Why Aren’t More Patents Leading to More Productivity? - Timothy Taylor

Plastic Recycling Is Broken. Capitalism Can Fix It. - Bberg Opinion

Investors are still underestimating the long-term impact of AI - FT Opinion

Venture capital reckons with the end of ‘megafund’ era - FT

Google Is More Resilient Than Its AI Stumbles Imply - WSJ

Business Schools Are Going All In on AI - WSJ

Can Africa one day help feed the world’s growing population? - FT

Policy

Sorry, But Joe Biden Can’t Build Your EV Charger - Bberg Opinion

California Turns Fast Food Into Higher-Skilled Work - Bberg Opinion

Collaboratively adding context to social media posts reduces the sharing of false news - Arxiv

Copyright policy options for generative artificial intelligence - Joshua Gans

AI

AI and personalized learning: bridging the gap with modern educational goals - Arxiv

An A.I. Researcher Takes On Election Deepfakes - NYT

Showing AI just 1000 extra images reduced AI-generated stereotypes - NS

The fine art of human prompt engineering: How to talk to a person like ChatGPT - Ars

Artificial Intelligence-Augmented Brainstorming: How Humans and Ai Beat Humans Alone - SSRN

Health

Artificial intelligence is taking over drug development - The Economist

Can 23andMe reinvent itself as a drug discovery company? - FT Opinion

Diabetes drug slows development of Parkinson’s disease - Nature

mRNA drug offers hope for treating a devastating childhood disease - Nature

Clean Energy

The hard lessons of Harvard’s failed geoengineering experiment - MIT Tech Review

How to Accelerate Wind Turbine Technology - IEEE

Robotics

Chinese robot maker says protectionism will not stop its march - FT

Space/Transportation

How will astronauts cruise around the Moon? NASA narrows choice to three options - Ars

NASA Picks 3 Companies to Help Astronauts Drive Around the Moon - NYT

Space experts foresee an “operational need” for nuclear power on the Moon - Ars

The race to fix space-weather forecasting before next big solar storm hits - MIT Tech Review

Up Wing/Down Wing

3 Body Problem stars on the show’s big question: would you push the button? - Verge

The Doomscroll Generation - Washington Monthly