What Hurricane Ida just taught us about how the US economy really works

Also: Here’s how we might power a Roaring Twenty-First Century . . . from space

“I am not at all impressed with people who tell me [landing on the Moon] is useless. It is only useless if we do not know how to use the experience.” - Jacob Bronowski, British scientist, historian, and the writer/narrator of the BBC series The Ascent of Man (as quoted in One Giant Leap by Charles Fishman).

In This Issue

The Micro Reads: Work from home, disruptive tech and jobs, English monasteries and the Industrial Revolution, and more . . .

The Short Read: Here’s how we might power a Roaring Twenty-First Century . . . from space

The Long Read: What Hurricane Ida just taught us about infrastructure and connectivity economics

The Micro Reads

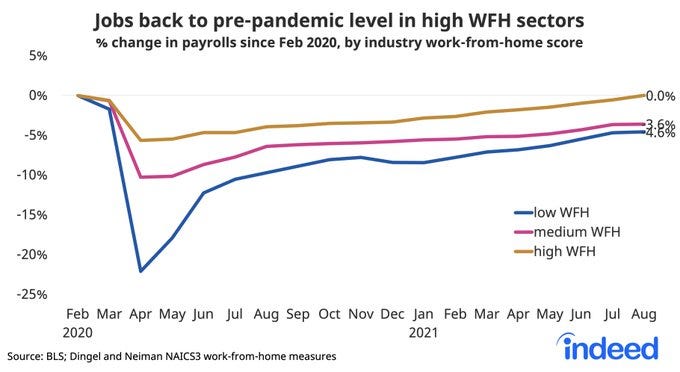

👷♂️ U.S. Payroll Growth Slowed in August - WSJ | One interesting aspect of this disappointingly weak report is how the tech-enabled WFH issue played out. The main weakness was in retail employment. And as Capital Economics noted, that “drop-off in high contact services employment growth suggests that, even though few states have re-imposed restrictions beyond mask mandates, the Delta variant is nevertheless weighing on activity by scaring off customers.” Likewise, JPMorgan pointed out that “the number of persons who teleworked last month increased for the first time since December.”

🤖 How Do Workers Adjust When Firms Adopt New Technologies? - Institute of Labor Economics | Econ 101 continues to absolutely crush it. This from researchers Sabrina Genz, Terry Gregory, Markus Janser, Florian Lehmer , and Britta Matthes: “We investigate how workers adjust to firms' investments into new digital technologies, including artificial intelligence, augmented reality, or 3D printing. . . . Depending on the type of technology, we find evidence for improved employment stability, higher wage growth, and increased cumulative earnings in response to digital technology adoption.” A tough beat here for those expecting trucker riots this decade.

🚀 NASA’s big rocket misses another deadline, now won’t fly until 2022 - Eric Berger, Ars Technica | The expensive comedy of errors continues. Meanwhile, over at SpaceX and Blue Origin …

✝ The Long-Run Impact of the Dissolution of the English Monasteries - The Quarterly Journal of Economics | It wasn’t just better science and technology that caused the Industrial Revolution. The great acceleration in progress and human welfare required a commercially-minded civilization in which to flourish as a precondition. This from researchers Leander Heldring, James A. Robinson, and Sebastian Vollmer:

We use the impact of the Dissolution of the English monasteries in 1535 to test the commercialization hypothesis about the roots of long-run English economic development. Before the Dissolution, monastic lands were relatively unencumbered by inefficient feudal land tenure, but could not be sold. The Dissolution created a market for formerly monastic lands, which could now be more effectively commercialized relative to nonmonastic lands, where feudal tenure persisted until the 20th century. We show that parishes impacted by the Dissolution subsequently experienced a ‘rise of the Gentry’, had higher innovation and yields in agriculture, a greater share of the population working outside of agriculture, and ultimately higher levels of industrialization.

📱 Regulators and Reality - Ben Thompson, Stratechery | “. . . in a perfect world with perfect regulators I still think the Instagram acquisition shouldn’t have happened, but you can no longer plausibly argue that Facebook has any sort of monopoly power; look no further than recent tech earnings, where the prevailing story was how company after advertising-supported company was absolutely crushing it, in stark contrast to six years ago when Facebook really did look unstoppable. The market worked.”

The Short Read

☀ Here’s how we might power a Roaring Twenty-First Century

This decade isn’t going to merit the New Roaring Twenties nickname if all we get is better social media functionality and moderation. I might even argue that returning to the Moon wouldn’t be enough, although it would be awesome. Been there, done that — even if it’s been 50 years since being there and doing that.

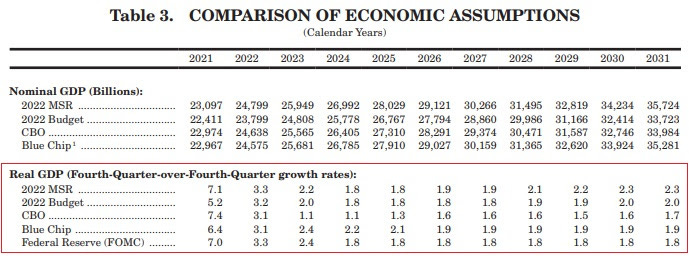

I think a New Roaring Twenties would require at least two things: First, a significant acceleration in productivity and economic growth. On this front, I would note that the new White House economic forecast, which tries to calculate the impact of President Biden’s economic agenda, does anticipate a better economy than we’ve seen since the years just before the Global Financial Crisis. Fingers crossed. Of course, I would also note that this rosy forecast is rosier than outside forecasts (likely because of a rosier productivity forecast):

Second, I think we need some advance in energy production that suggests a future where energy won’t just be cleaner, but also more abundant. Maybe that’s nuclear fission/fusion. Maybe that’s geothermal. Or maybe it’s the kind of solar that wouldn’t have to deal with NIMBY things like this:

The push to transition from carbon-emitting fuel sources to renewable energy is hitting a roadblock in Nevada, where solar power developers are abandoning plans to build what would have been the United States’ largest array of solar panels in the desert north of Las Vegas. . . . California-based Arevia Power [contended] that its solar panels would be set far enough back on Mormon Mesa to not be visible from the valley. But a group of residents organized as “Save Our Mesa” argued such a large installation would be an eyesore and could curtail the area’s popular recreational activities — biking, ATVs and skydiving — and deter tourists from visiting sculptor Michael Heizer’s land installation, “Double Negative.”

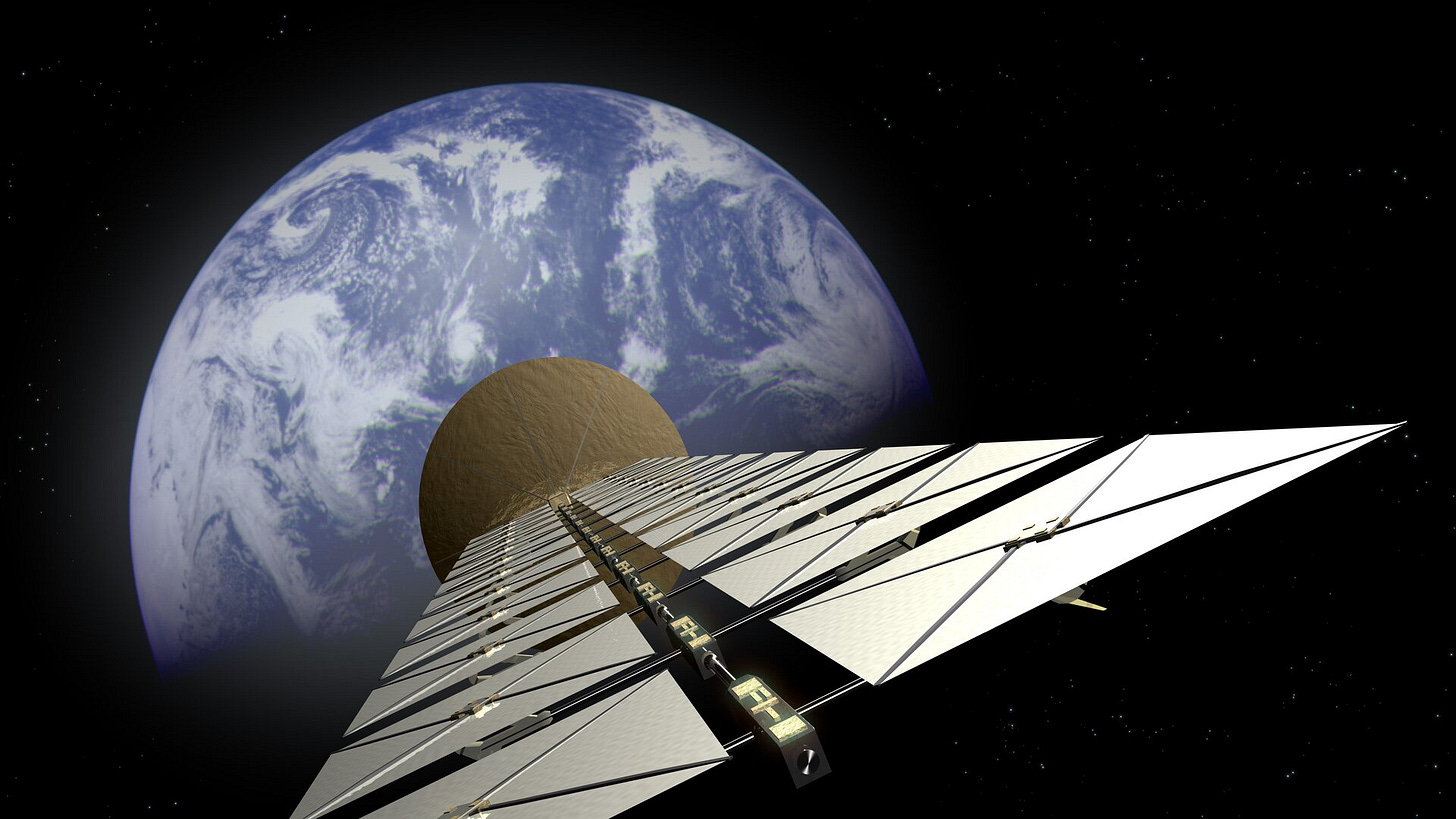

So how about putting those solar panels up in orbit away from green activists and then beaming the energy down to Earth? The idea of space-based solar power has been around since at least 1941 when science fiction writer and futurist Isaac Asimov wrote about the idea in his short story, Reason. But satellite miniaturization and the sharp drop in launch costs means fiction is closer than ever to becoming fact.

From the Financial Times:

China, the US, Europe and Japan are all developing projects. Beijing even plans to have a working system by the 2030s, according to reports from China-based media. In September, the UK government will signal it too wants to explore the technology’s potential. It will publish findings of a new study examining how space solar might help Britain achieve a net zero economy by 2050. The report, prepared by consultants Frazer-Nash with input from European companies such as Airbus and Thales Alenia Space, concludes that space-based solar power is not only technologically possible, it argues that the lifetime cost per megawatt hour could be half that of nuclear power.

By the way, that Chinese effort envisions a space-based power station capable of generating at least a megawatt of electricity by 2030, and a commercial-scale solar power plant in space by 2050. Let’s go, America! Faster, please!

The Long Read

🌀What Hurricane Ida just taught us about infrastructure and connectivity economics

“The New York area awoke to a flood-ravaged and largely paralyzed landscape on Thursday,” is how the New York Times described the impact of record-breaking rains from the stormy remnants of Hurricane Ida. So given flood-related transit difficulties and plenty of cleanup to do, it’s probably not been a record-breaking week for business productivity in the greater metropolitan area.

And you can at least partially blame that reality on a lack of productivity in preparing for another big storm in the post-Hurricane Sandy era. Back in April, The City news site reported that dozens of key projects in an $8 billion, nearly decade-long effort to make the subway system more storm resilient remain unfinished, “including erecting miles of protective walls around subway yards in Upper Manhattan and Coney Island.”

I mention this because it drives me crazy that so often the benefits of infrastructure investment seem to revolve around safer bridges and “good jobs” for blue-collar workers. But the latest flooding disaster in NYC shows how inadequate infrastructure can disrupt a key node in America’s economic network. And that is exactly what New York is. Every year it generates more than $1 trillion in high-productivity economic output, and is typically second behind Silicon Valley as a high-impact startup hub. The classic economic assessment of the impact from infrastructure spending focuses on lowering business costs, reducing commute times, improving labor force participation, and reducing pollution. But keeping a key tech and productivity hub online is pretty important, too.

I guess at its heart infrastructure is about keeping America’s various economic hubs connected and operating. And that doesn’t just mean cities. Companies and colleges are also economic hubs. I find it helps when thinking about pro-progress policy to imagine the $21 trillion US economy as a network of networks connecting these various hubs or nodes. And what do each of these nodes do? They process information. And I use that word “information” in a special way: the physical arrangement of atoms. And the ability to arrange atoms in ways we find valuable — a Tesla, an iPhone, a Diet Coke — is called knowledge.

In a 2018 podcast chat with a statistical physicist Cesar Hidalgo, author of the brilliant Why Information Grows: The Evolution of Order, from Atoms to Economies, my guest described this information-based approach to seeing our civilization as such:

If you take a deck of cards and you shuffle it, you don’t change the mass, you don’t change the energy, but you change the information that it contains. And the creativity of our universe and our economy depends on our ability to create information, to change the way in which things are ordered. In the book I say that the big difference between the world that we have today and the world that we had 100,000 years ago is not the atoms that are available in our planet. Those are all the same. The only thing that has changed is the way we will have arranged them, and also our ability to arrange them.

And what are the policy implications of this sort of framing if you value economic growth? Well, you need each of those information-processing nodes to be vital. So cities not underwater, companies innovative, schools effective. But more broadly, you want a country that is effective at connecting (Yay, good infrastructure! Yay, global supply chains! Yay, making it more affordable for people to live productive urban hubs. Yay, immigrants. Yay, free trade!) and learning. Again, Hidalgo:

If you go to any grad school program like in physics or chemistry or computer science, at least half of the students there are going to be very talented kids from all over the world. And in that context, all of these talented groups of people bring together the ability to create and produce vast amounts of new knowledge, and that ends up becoming part of the economy a few years down the line, and sometimes even quite immediately. . . . So in that context the policy implications are ones that are very much pro-movement of people, because people are the carriers of knowledge. That knowledge only gets combined as people get to interact. . . . [And] that knowledge is something that is too large for a single person to hold. [So] we need to create diverse networks and diversity in the minds of people. You create these unique things when we combine different knowledge.

And those “unique things,” whether a Tesla, iPhone, or Diet Coke, are the result of knowledge being used to arrange atoms into, as Hidalgo puts it, “crystals of imagination.” And rich nations are better as creating dense, information-packed crystals of imagination. That’s why they’re rich nations. Yes, I know this sounds like economic policy from the Marianne Williamson, but it makes a lot of sense — as does improving US productive capacity by improving its infrastructure.