⤴ We don't need exponential growth for a fantastic future

Also: 5 Quick Questions for … regulation expert James Coleman on permitting reform, energy infrastructure, and more

In This Issue

The Essay: We don't need exponential growth for a fantastic future

5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for … regulation expert James Coleman on permitting reform, energy infrastructure, and more

Micro Reads: gloomy consumers, an Alzheimer’s drug, peak oil, and more ….

Quote of the Issue

“How we feel about the evolving future tells us who we are as individuals and as a civilization: Do we search for stasis—a regulated, engineered world? Or do we embrace dynamism—a world of constant creation, discovery, and competition? Do we value stability and control, or evolution and learning” - Virginia Postrel, The Future and Its Enemies: The Growing Conflict Over Creativity, Enterprise

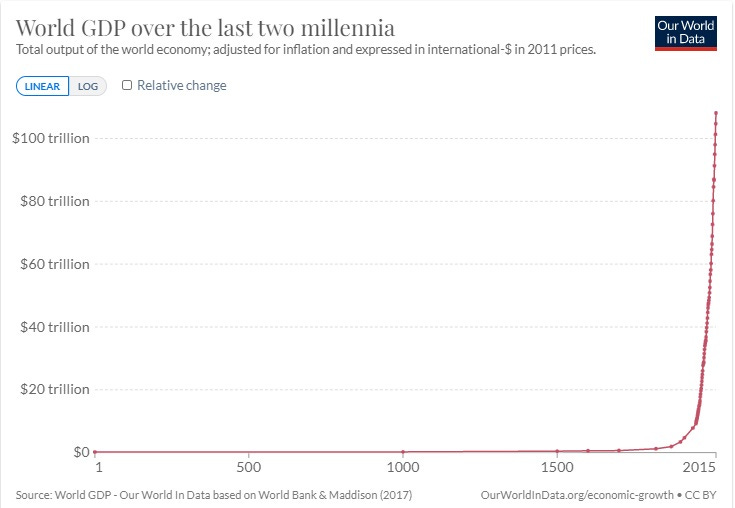

Faster, please! But how fast, exactly? What does human history tell us about the potential rate of human economic progress? What’s possible? The following chart, which I have called The Most Important Economic Chart in History™, suggests extraordinarily rapid progress is possible:

The modern world is the result of economic growth accelerating from nothing to almost nothing to something. To put actual numbers on that acceleration: “It took thousands of years for growth to increase from 0.03 percent to 0.3 percent, but only a few hundred years for it to increase from 0.3 percent to 3 percent,” notes researcher Tom Davidson in a report for Open Philanthropy “Could Advanced AI Drive Explosive Economic Growth?” Davidson continues: “If you naively extrapolate this trend, you predict that growth will increase again from 3 percent to 30 percent within a few decades.”

But the argument here isn’t just about extrapolating historical trends to the stratosphere. As the title of the report suggests, advances in AI might provide the mechanism for another upward leap. Perhaps the most obvious way is through machines substituting for human labor. “If capital can replace labor entirely, growth rates could explode, with incomes becoming infinite in finite time,” write economists John Fernald and Charles Jones in a 2014 paper for the San Francisco Fed.

But for me, the more intriguing aspect is what Davidson calls the “ideas feedback loop.” It comes from the notion that people generating ideas is the core of innovation-driven growth. As Charles Jones writes in a different paper, “The Past and Future of Economic Growth: A Semi-Endogenous Perspective”:

Where do ideas come from? The history of innovation is very clear on this point: new ideas are discovered through the hard work and serendipity of people. Just as more autoworkers will produce more cars, more researchers and innovators will produce more new ideas. … People produce ideas and, because of nonrivalry … more colloquially, infinitely usable … those ideas raise everyone’s income. This means that income per person depends on the number of researchers. But then the growth rate of income per person depends on the growth rate of researchers, which is in turn ultimately equal to the growth rate of the population.

Now here’s Davidson’s take on this idea:

Idea-based models explain increasing growth with an ideas feedback loop: more ideas → more output → more people → more ideas… Idea-based models seem to have a good fit to the long-run GWP data, and offer a plausible explanation for increasing growth. … After the demographic transition in about 1880, more output did not lead to more people; instead people had fewer children as output increased. This broke the ideas feedback loop, and so idea-based theories expect growth to stop increasing shortly after the time. Indeed, this is what happened. Since about 1900 growth has not increased but has been roughly constant. … Suppose we develop AI systems that can substitute very effectively for human labor in producing output and in R&D. The following ideas feedback loop could occur: more ideas → more output → more AI systems → more ideas… Before 1880, the ideas feedback loop led to super-exponential growth. So our default expectation should be that this new ideas feedback loop will again lead to super-exponential growth.

As regular Faster, Please! readers know, this newsletter has previously explored the potential of AI accelerating the idea discovery process. For example, there’s the AlphaFold “deep learning” AI system developed by Google’s DeepMind that can accurately predict 3D models of protein structures and, we hope, will significantly reduce the time required to make biological discoveries. Complementing the DeepMind breakthrough, MIT Technology Review reports, is a new AI tool that “when harnessed could help unlock the development of more efficient vaccines, speed up research for the cure to cancer, or lead to completely new materials.” Imagine building a DALL-E or GPT-3 for science.

So what is the case against warp-speed growth of the sort Davidson optimistically speculates about?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faster, Please! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.