💥💥 Two takes on America’s emerging (maybe) productivity boom

'In our opinion, the productivity growth boom has been underway since the end of 2015'

Quote of the Issue

We are facing a strangely paradoxical situation in the way cities are managed: the professionals in charge of modifying market outcomes through regulations (planners) know very little about markets, and the professionals who understand markets (urban economists) are seldom involved in the design of regulations aimed at restraining these markets.” Alain Bertaud, Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities

The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised

“With groundbreaking ideas and sharp analysis, Pethokoukis provides a detailed roadmap to a fantastic future filled with incredible progress and prosperity that is both optimistic and realistic.”

The Essay

💥💥 Two takes on America’s emerging (maybe) productivity boom

I recently wrote a Faster, Please! essay asking whether the Great Upshift — a sustained period of surprisingly rapid productivity and economic growth — had started. The data points that lead me to ask the question: Strong productivity growth over the past three quarters, especially coming amid what appears to be a new technology revolution. Kind of 1990s vibe where a boom started just at the point that many economic analysts, commentators, and journalists had resigned themselves to a permanent Great Downshift or Great Stagnation.

Of course, I’m not the only person still thinking about the possibility of a New Roaring ’20s — followed, I hope, by a Thrilling Thirties, Fantastic Forties, and beyond. Here are two interesting new perspectives worthy considering;

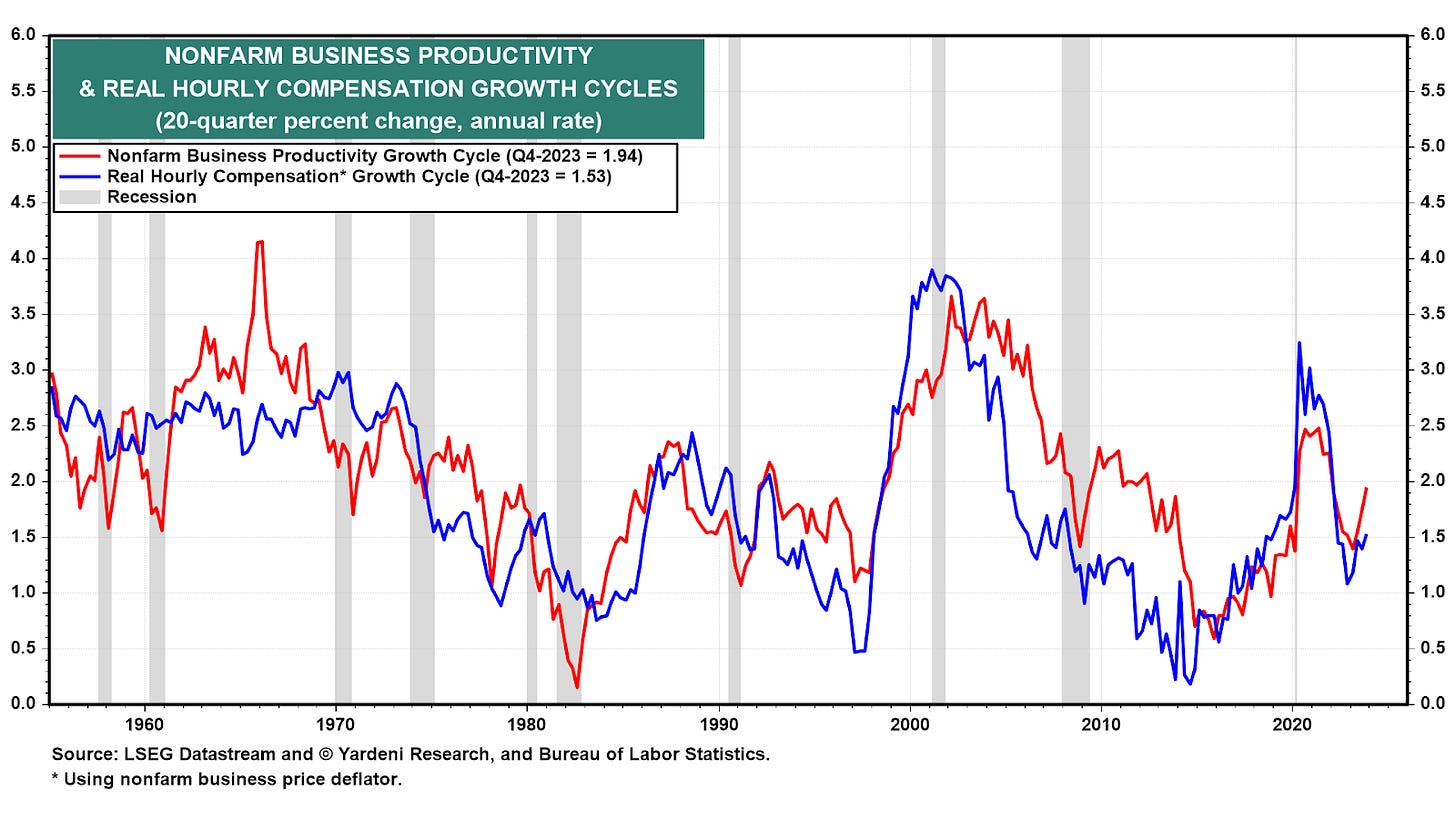

Investment strategist Edward Yardeni

Ed Yardeni was one of Wall Street’s great bulls during the boomy 1990s. And guess what? He’s pretty bullish again. As the analyst sees things, the Covid-19 pandemic momentarily derailed his productivity-driven "Roaring 2020s" vision for the decade. But the recent data is signalling what could be a powerful resurgence. (Although productivity numbers are notoriously volatile, Yardeni notes in a report earlier this week that productivity and real hourly pay are closely linked over five-year cycles because the former determines the latter, which is the main driver of workers’ purchasing power and prosperity. “The growth rate of real hourly compensation continues to track and to confirm the growth rate of productivity.”)

With productivity growth outpacing historical averages over the past three quarters, Yardeni thinks we may well be witnessing the early stages of a significant economic transformation. Fueled by technological advancements and the need to overcome chronic labor shortages, it could dramatically enhance productivity. “If so, the ramifications for economic growth would be profound,” he writes in “Productivity Is Roaring Back.”

How profound, precisely? Yardeni:

Over the past five years through Q4-2023, real GDP rose 2.1% at an annual rate with the labor force up only 0.6% and productivity rising 1.5%. Over the remaining six years of the current decade, the labor force should increase 1.0% and productivity should increase by at least 2.5% and perhaps as much as 3.5% in the Roaring 2020s scenario. That would result in real GDP growth of 3.5%-4.5%. In fact, that’s a conservative forecast given that during the previous three productivity growth booms, the five-year trailing peaks ranged between 3.0% and 4.1%. … [In] our opinion, the productivity growth boom has been underway since the end of 2015 and is back on an ascending track following a volatile period with a big up and then a big down move during the pandemic.

Capital Economics

In a new report, “Has a new productivity boom begun?,” the UK-based economics consultancy looks at the potential start of a new productivity boom in the American economy:

The rapid decline in inflation back towards the Fed’s target even as GDP growth has accelerated suggests the US is experiencing something of an economic miracle. But that stellar performance is less of a surprise given the resurgence in the economy’s supply side, with labor force and productivity growth accelerating to their strongest pace in years. … The 2.7% growth of non-farm business productivity last year was well above the pre-pandemic average of 1.5% and, excluding the brief surge in the early stages of the pandemic, was the strongest reading in more than a decade. … The US experience stands in stark contrast to that of most other advanced economies, where productivity growth has generally been weak or negative in recent quarters. But it’s worth noting that the alternative non-financial corporate sector measure of productivity growth – which was favoured by former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan – hasn’t been nearly as strong. That’s because it is measured using the income side of the national accounts rather than expenditure side, and therefore reflects the relative weakness of Gross Domestic Income over the past year. Nevertheless, it is hard to find convincing evidence that GDP and by extension productivity in the non-farm business sector are significantly overstating the economy’s strength, particularly not when inflation has fallen markedly.

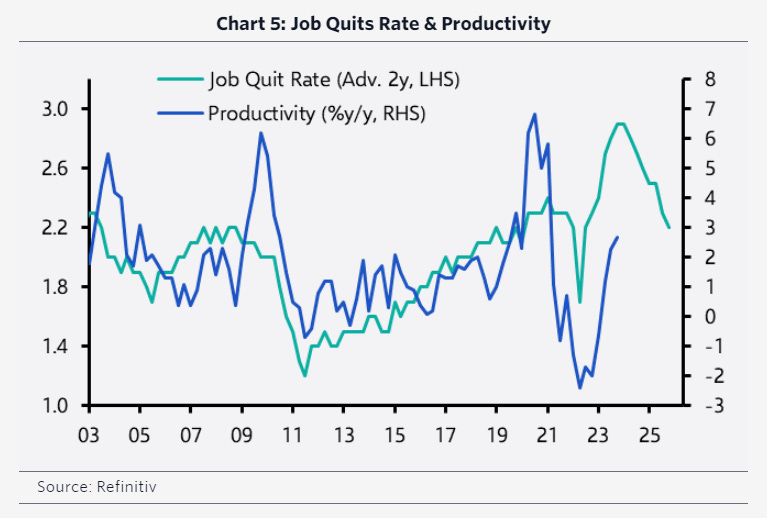

So what’s probably going on with productivity, at least from CE’s perspective? The recent productivity upshift is a cyclical response to a tight hiring environment, one that compels firms to boost efficiency and automation. CE highlights a historical trend that when companies report increasing difficulties filling job vacancies, productivity growth tends to accelerate.

CE: “At face value, the unusually high level of the NFIB jobs hard to fill index suggests the recent productivity acceleration could still have much further to run. Voluntary quits, although back down to pre-pandemic levels, also point to further strong gains in productivity.”

One other labor market effect on productivity: Due to the pandemic, more people than usual have switched to new jobs in recent years. In theory, this big change should lead to better productivity over time because people tend to move to jobs where they fit better or have more opportunity to rise — at least once they get the hang of their new gigs. “Nevertheless, the temporary period of elevated churn implies a one-time boost to the level of productivity, rather than an ongoing boost to growth.”

The bottom line:

Overall, there is evidence that productivity growth has enjoyed a boost from the strength of labor market conditions over the past couple of years. That boost is likely to start easing soon with employment growth trending gradually lower and most indicators of slack moving back towards more ‘normal’ levels. But the trend of firms becoming more efficient in response to dwindling spare capacity is far from unique to the past couple of years and had already emerged prior to the pandemic. The upshot is that, assuming a significant downturn is avoided and that labor market conditions remain relatively strong, there should be scope for productivity growth to stabilize around that slightly stronger 2017-19 trend.

As for AI, the report acknowledges the significant potential of machine learning, particularly generative AI, as a general purpose technology (GPT) that could deliver a considerable boost to productivity growth. Despite the potential, however, CE points out the current lack of compelling evidence directly linking AI to the surge in productivity.

For example: There doesn't appear to be a significant AI-related increase in business investment. And dectors reporting the highest usage of AI technology don't necessarily correlate with those experiencing the strongest productivity growth. In short, AI adoption isn't yet widespread enough across the economy to drive the observed productivity gains, with only a small percentage of firms currently using AI in their operations.

CE: “A significant and lasting productivity boost from the AI revolution remains a key upside risk to the economic outlook for the next few years. But there isn’t much evidence that new AI technologies are behind the recent resurgence in productivity growth.”

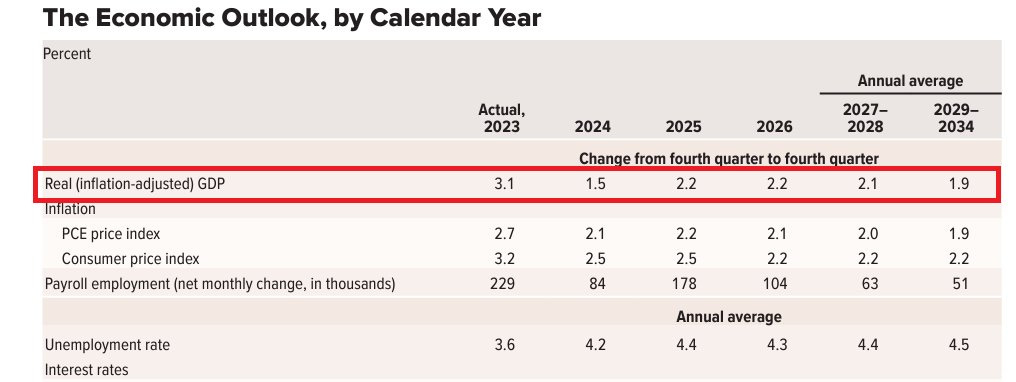

Let’s hope the CE take is a worst-case scenario: An AI-driven boom is possible but hasn’t appeared yet. After all, AI may be the key to avoiding a long-term, slow-growth future of the sort found in the new ten-year forecast from the Congressional Budget Office. Two percent is too darn slow.

Micro Reads

Business and Economics

Why Is Prime-Age Labor Force Participation So High? - SF Fed

Microsoft’s next big AI push is here after a year of Bing - The Verge

The Italian town where tensions are flaring over migrant workers - FT

Tech Firms in Japan Are Scouring for Talent Amid Labor Shortage - Bloomberg

Meta Finally Figures Out How to Sell the Metaverse - WSJ

Meta Calls for Industry Effort to Label A.I.-Generated Content - NYT

Has Intergenerational Progress Stalled? Income Growth Over Five Generations of Americans - Kevin Corinth and Jeff Larrimore, Federal Reserve

Policy

How can the world provide a better education to the next generation? - Our World in Data

China on cusp of next-generation chip production despite US curbs - FT

Universities are failing to boost economic growth - Free Exchange, The Economist

AI

Summon a Demon and Bind it: A Grounded Theory of LLM Red Teaming in the Wild - Arxiv

Which Tasks are Cost-Effective to Automate with Computer Vision? - Neil Thompson, Stanford HAI

On holding back the strange AI tide - Ethan Mollick, One Useful Thing

Designing Chips Is Getting Harder. These Engineers Say Chatbots and AI Can Help. - WSJ

AI’s bioterrorism potential should not be ruled out - Anjana Ahuja, FT Opinion

Behind the Screen: Investigating ChatGPT's Dark Personality Traits and Conspiracy Beliefs - Arxiv

Health

Revolutionizing Vision Restoration Through Artificial Intelligence -SciTechDaily

Clean Energy

5 questions for David Ulevitch of Andreessen Horowitz - Politico

Nuclear fusion reaction releases almost twice the energy put in - New Scientist

Six Big Ways Climate Change Could Impact the United States by 2100 - Smithsonian

How virtual power plants are shaping tomorrow’s energy system - MIT Tech Review

Stanford Lithium Metal Battery Breakthrough Could Double the Range of Electric Vehicles -SciTechDaily

Ecomodernism: A clarifying perspective - Sage Journals

The Earth is getting greener. Hurray? - Vox

Space/Transportation

Asteroid sampled by NASA may once have been part of an ocean world - New Scientist

Saturn’s tiny moon Mimas seems to have an ocean, too - Ars Technica

Up Wing/Down Wing

Only America Can Save the Future - Ross Douthat, NYT Opinion

The New Luddites Aren’t Backing Down - New Atlantic

I doubt that AI is going show up in productivity figures so early in the game. So I agree that the labor market is the reason for the upshift. This is why central banks should probably formally adopt NGDP targeting... to keep the labor market tight.

We want a tight labor market as this pushes up wages and drives innovation.

got spoiled with the links today. great as always! thanks james.