They promised we could control hurricanes, but instead we got Twitter

Also: What Soviet science cities and the Spanish Inquisition tell us about long-termism

“Greater production is the key to prosperity and peace. And the key to greater production is a wider and more vigorous application of modern scientific and technical knowledge.” - President Harry S. Truman

In This Issue

The Long Read: They promised we could control hurricanes, but instead we got Twitter

The Short Read: The past isn't even the past: What Soviet science cities and the Spanish Inquisition tell us about long-termism

The Micro Reads: space elevators, Tesla Bots, the metaverse, and more. . .

The Long Read

🌧 They promised we could control hurricanes, but instead we got Twitter

Maybe we’ve made enough progress with air taxis that “They promised flying cars, but instead we got Twitter” doesn’t work anymore as a snarky metaphor for technological stagnation. But there are other postwar expectations about tech progress that could serve as a substitute. “They promised intelligent apes, but instead we got Twitter” would be one option. Neither the Planet of the Apes franchise (five films from 1968 through 1974) nor the 1963 book it was based on came purely from imaginative writers. Forecasts about artificially enhanced ape intelligence were a staple of the era’s futurist predictions. For instance: A 1964 RAND Corporation survey of experts pegged 2020 as the median prediction as to when smart simians would be available for “low-grade” labor or even military reconnaissance and combat operations. Clearly a different vision of how (human) driverless cars might work.

Or this option: “They promised weather control, but instead we got Twitter.” If you were a naval strategist in the 1960s who found yourself musing about the tactical implications of weather control — such as the ability to whip up a hurricane and hurl it at an enemy fleet — scientists offered encouraging news. The 1968 book Toward the Year 2018 was a compilation of expert forecasts, published by the Foreign Policy Association. It included an entire chapter on weather, written by Thomas F. Malone, director of research at Travelers Insurance and chair of the Committee on Atmospheric Sciences of the National Academy of Science. Malone believed “the next fifty years will be crucial for controlling, to a significant extent, this particularly sensitive part of our physical environment.”

Regional weather modification and control — increase rainfall, reduce hail, suppress lighting — seemed quite possible, with even wide-scale weather control, including hurricanes, given a 50-50 chance over the next half century. (That RAND survey found a median prediction of 1990 as to when we would be capable of enough weather control to destroy an enemy’s crops or flood its territory.) Malone seemed more concerned about international agreements to coordinate weather inventions than the potential success of those interventions. Little wonder, given such high confidence, that the immediate postwar decades were a boom time for experimentation. One of the most well known US government projects was Project Stormfury, an attempt to weaken hurricanes by having aircraft seed them with silver iodide.

Flash forward 50 years: We’re not doing much intentional weather control, although we are obviously affecting the climate, which does affect the weather. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration gives a handy rundown of the many failed ideas, such as the Stormfury Project. Yet climate engineering is again front of mind in a way it hasn’t been since the 1960s. This is due to growing awareness of climate change, as well as greater recognition that humanity is unlikely to take the steps necessary to minimize global warming through reduced carbon emissions from lifestyle changes. And every time there’s a big hurricane, such as the one which slammed into Louisiana over the weekend, concern about extreme weather intensification, well, intensifies.

And rightly so. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, “Climate change is expected to affect tropical cyclones by increasing sea surface temperatures, a key factor that influences cyclone formation and behavior. The U.S. Global Change Research Program and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change project that tropical cyclones will become more intense over the 21st century, with higher wind speeds and heavier rains.”

Moreover, that’s just one of many worrisome impacts. From the new analysis “Global weather disruptions, food commodity prices, and economic activity: A global warning for advanced countries”: “There will be more frequent and greater downturns in economic activity compared to a ‘no climate change’ scenario through increases in global food commodity prices that are the consequence of extreme weather events in major agricultural production regions, such as droughts and heatwaves.” Oh, and those higher temperatures are also bad for worker productivity.

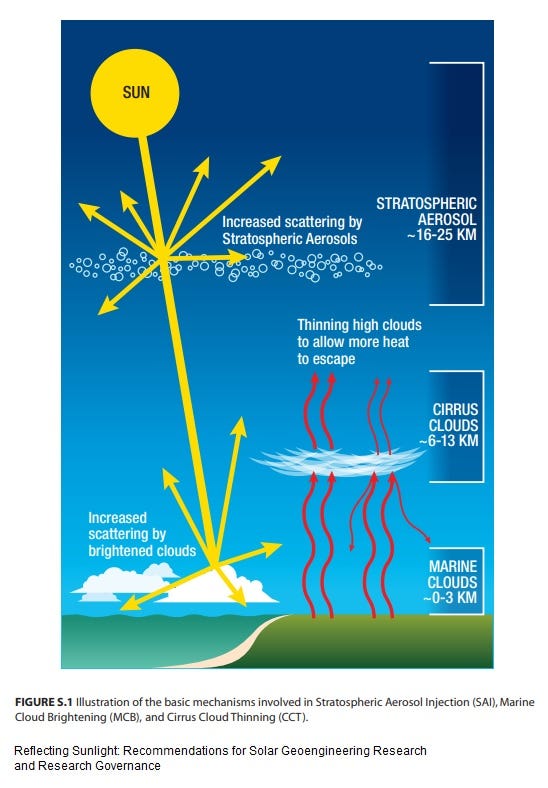

If we don’t decide to massively change and downgrade our lifestyle (or, preferably, push hard for tech innovation and deployment) and some of the worst scenarios look to be happening, one option is climate engineering. Yup, we’re back to weather control and modification. This could mean reforesting the Sahara, building carbon capture machines, or spraying stuff into the atmosphere to reflect some sunlight. Solar radiation management, in particular, was once treated like a mad scientist’s diabolical scheme.

Less so today. A recent report from the National Academies of Sciences recommends America “pursue a research program for solar geoengineering. . . to better understand solar geoengineering’s technical feasibility, possible impacts on society and the environment, public perceptions, and potential social responses — but it should not be designed to advance future deployment of these interventions.”

Yet objections remains to even discussing geoengineering, much less researching it. The complaint: It’s a cheap, break-the-glass strategy that would make it less likely we take pricier and longer-term actions to reduce emissions. This critique was recently analyzed by Daniel Bodansky and Andy Parker in “Research on Solar Climate Intervention Is the Best Defense Against Moral Hazard” in the summer 2021 issue of Issues in Science and Technology. Bodansky and Parker note that opponents to Sweden’s 2021 solar engineering experiment — releasing tiny quantities of reflecting particles into the stratosphere— warned, successfully, that it was a slippery slope to even more experimentation.

But Bodansky and Parker cite evidence undercutting this moral hazard argument. Take the idea of fertilizing the ocean with iron to encourage algae growth. The algae bloom would theoretically pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and then when the bloom died, it would sink to the ocean bottom, trapping the carbon. But when experiments underwhelmed, “ocean iron fertilization dropped down the policy agenda. Informed by the field research, major policy reports cooled on it, and attention from policymakers and research funders was redirected to other, more promising forms of carbon dioxide removal.”

There was no slippery slope. Indeed, more information about geoengineering might create a reverse moral hazard effect. Again, from the analysis:

For example, a team at Yale University sought to test directly the moral hazard argument by assigning study participants in the United Kingdom and United States to two groups: one group was given information about climate intervention as a response to global warming; the other was given information about regulating pollution. The study’s results were remarkable. The researchers found that the group exposed to information about climate intervention was slightly more concerned about climate change risks. That is, they found evidence of a reverse moral hazard response. This research might be dismissed as an academic curiosity, but the same reverse moral hazard effect has been observed using different study methods in Germany, Sweden, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

The 1960s efforts stopped both because of scientific roadblocks and a certain squeamishness about technological fixes at a time when environmentalists painted tech as an obstacle to restoring the planet’s natural “balance.” Let’s not make the same mistake again.

The Short Read

🔮 The past isn't even the past: What Soviet science cities and the Spanish Inquisition tell us about long-termism

This newsletter is meant to contain a wide streak of humility. Yes, it envisions a future of longer, healthier lifespans and global abundance and multiplanetary civilization. To paraphrase Loki Laufeyson, Faster, Please! is filled with glorious purpose.

Yet while highlighting intriguing technological developments and public policies to encourage even more innovation, Faster, Please! won’t offer a specific route forward. There’s no master plan other than aiming to create a pro-progress economic and cultural ecology where resilience comes from wealth. And then we’ll see what happens, although history suggests what happens will be pretty awesome.

One way to describe this approach is “Burkean long-termism.” And although while writing this Substack I’ve thought a lot about Edmund Burke and long-termism, I have to credit Leopold Aschenbrenner, a research fellow in economics at Forethought Foundation, for creating the exact phrase (at least as far I know). As he writes in a recent essay, “Burkean Longtermism”:

We ought to have a deep concern for the distant future. . . . The concern for the future is concrete: what do we pass along to our posterity, our own children and children’s children and their children? With this acute sense of the long arc of time comes not just care for that which we pass along, but also appreciation for that which we have inherited. . . . We should take epistemic humility extremely seriously. . . . Many of our forebearers’ most fervent beliefs have been overturned by the test of time; many of ours will be too. In turn, this means skepticism about any specific views derived from pure reason. Rather, we should place our faith in mechanisms of error correction, experimentation, competition, adaptation.

But beyond that, who knows? As Friedrich Hayek famously put it, “The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.” Policymakers don’t start with some socioeconomic blank slate and never will. History abides, as three recent studies suggest:

“The long-run effects of R&D place-based policies: Evidence from Russian science cities” finds that Soviet-era science cities “still host a more educated population, are more economically developed, employ a larger number of workers in R&D and [information and communications technology]-related jobs, and apply for more patents than the comparable localities at the time of the programme's inception.” These middle-sized urban areas, nearly 100, were chosen during the Cold War as places to locate military R&D facilities. Selection was prioritized for “secrecy and safety from foreign interference,” rather than any economic considerations.

“Long-term effects of the Inca Road” finds a positive and statistically significant relationship between current proximity to the Inca Road, the extensive transportation system of pre-Columbian South America, and higher hourly wages, greater school attendance, greater length of schooling, reduced probability of malnutrition, and increased holding of property rights.

“Expecting the Spanish Inquisition: Economic backwardness and religious persecution” finds that areas that suffered more from the nearly 400-year long religious persecution — from 1478 through 1834 — “are today more religious and less educated, and they exhibit less generalised trust. The adverse impact on output, education, and trust is robust to a wide variety of additional controls.”

Plenty of other studies also vividly illustrate how, as William, Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead. It's not even past." Roman road networks predict the location of modern infrastructure and economic activity. The richest people in 1427 Florence, Italy have the same surnames as the top earners in that city today. Areas of London struck by German bombs in World War II have 7 percent more gang activity than those that weren’t. I could go on and on, as does the contract between humanity past, present, and future.

The Micro Reads

🌙 Space Elevators: How a sci-fi dream could be built - Chris Taylor, Mashable | “We’re talking super-tall, super-thin tethers that deliver people, satellites and other goods to high Earth orbit in elevator cars the size of trains. If the scientists and engineers who have been theorizing about the Elevator since the 1960s are right, then this is the most ingenious method ever devised for escaping our clingy little gravity well — which is responsible for at least 90 percent of the cost of getting to space.”

🤖 Here’s why Elon Musk’s robot is electrified neoliberalism - Van Badham, The Guardian | Among the many wrongheaded ideas in this piece — beyond, of course, the Lump of Labor Fallacy — is the suggestion that automation is only complementary to human work if mandated by government or unions. Spreadsheets, anyone?

🏃♂️ Why Company Headquarters Are Leaving California in Unprecedented Numbers - Joseph Vranich and Lee Ohanian, Hoover Institution | “Obtaining permits from state, regional, and local agencies in California to build any type of facility is extraordinarily expensive and time-consuming because of confusing, extraneous, and harsh requirements and bureaucratic delays. The length of time required for one fast-food restaurant to obtain a building permit in Los Angeles is 285 days while it’s only 60 in Texas.”

🕹 China Limits Online Videogames to Three Hours a Week for Young People - WSJ | What are the downsides to the new exertion of government control? Hard to see how it makes China a more creative and imaginative (and fun) place. I would also note research finding that kids who play Fortnite cooperatively feel more upbeat and competent afterward.

🧠 We should be careful which metaverse we choose to live in - John Thornhill, Financial Times | “A universal metaverse will take decades of infrastructure development and billions of dollars of investment to become reality. Facebook has big ambitions for its Oculus VR business, but even Zuckerberg accepts that clunky VR headsets limit entry into the metaverse. Facebook will first have to compress a supercomputer into 5mm-thick glasses to encourage mass adoption.”