🎁 The War on Gifted Education

Why the landslide loss for San Francisco's school board is a victory for American meritocracy

In This Issue

The Essay: Why the landslide loss for San Francisco's school board is a victory for American meritocracy — and economic growth

5QQ: Five Quick Questions for … policy and politics commentator Matthew Yglesias

Micro Reads: AI and nuclear fusion; improving supply chains; the rise of engineers during the Industrial Revolution; and more . . .

Nano Reads

Quote of the Issue

“If we have a world in which China is harnessing the meritocratic idea to reinforce the power of the Communist Party, the communist state, and America, at the same time, is dismantling meritocracy or softening meritocracy — then America loses. China becomes a massive version of Singapore. America becomes, I don’t know, a version of Brazil or something like that, and you lose. They win.” - Adrian Wooldridge

💥 Important Update for My Wonderful Faster, Please! Readers and Subscribers

I currently intend to start offering a paid subscription option to Faster, Please! as of February 28. While I’m still working out the exact details, accessing my twice-weekly essays and Q&A interviews with top thinkers (along with some surprises) would be included in that paid subscription, but not the freebie version. I have been writing this newsletter over the past year at night and on weekends. I hope you find it valuable.

My friends: I believe we’re at the start of an amazing period of American (and world) history — the beginning of a Great Acceleration in human progress. It’s the purpose of Faster, Please! both to document these steps/leaps forward and recommend the best ideas to make sure they happen, ASAP. You know, faster, please! I look forward to taking that journey — via economics, tech, public policy, business, history, culture, and a smidgen of politics — over the next months and years with all of you. Let’s make a better world for everyone, together. Melior mundus

The Essay

The landslide loss for San Francisco's school board is a victory for American meritocracy — and economic growth

There was a lot happening in that stunning San Francisco election on Tuesday when voters overwhelmingly chose to oust three members of the city’s Board of Education. Like in many other places across America, parents were frustrated that schools have been slow to reinstitute in-person instruction.

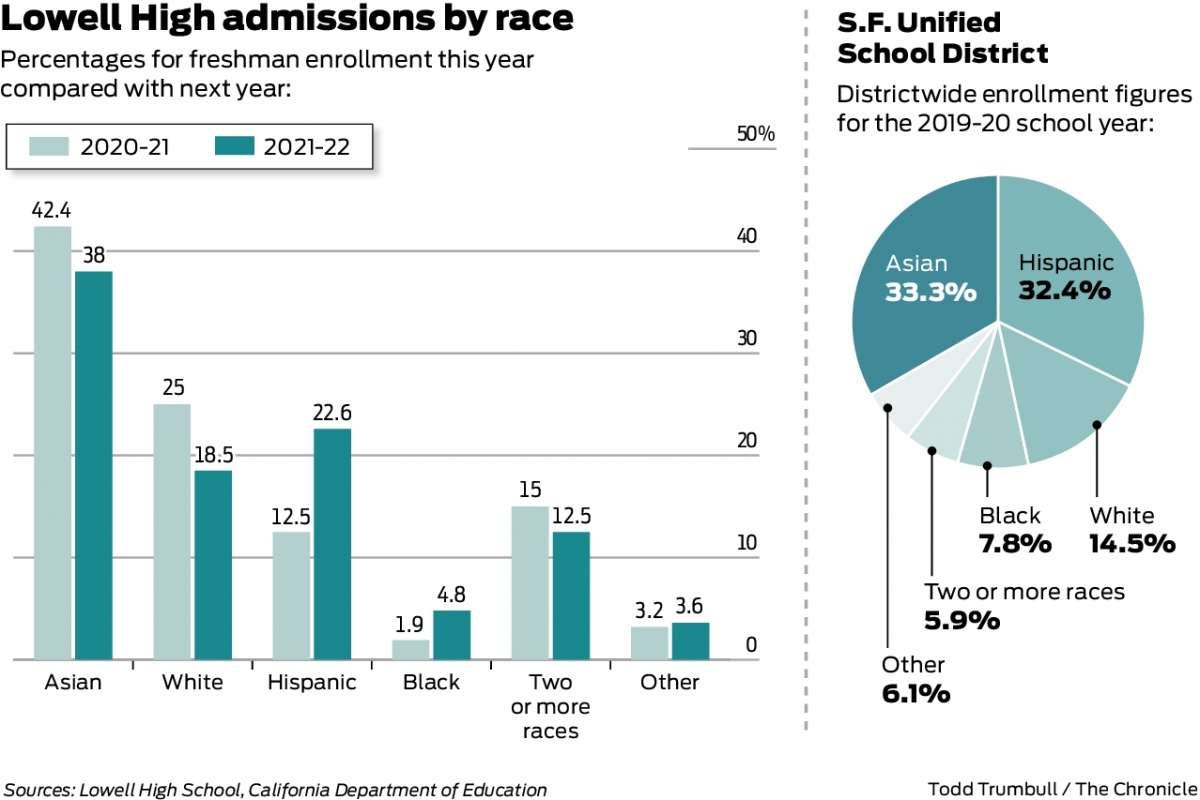

But as The New York Times reports, the critical factor at play may have been Asian-American anger that “the school board introduced a lottery admission system for Lowell High School, the district’s most prestigious institution, abolishing requirements primarily based on grades and test scores.” One Chinese-American mom with two kids in a local public high school told the NYT that the value of education “has been ingrained in Chinese culture for thousands and thousands of years.”

Central to that cultural history has also been the notion of meritocracy, going back to the Mandarin bureaucrat-scholars who obtained their positions through the imperial examination system. More recently, China’s communists have attempted to run a more vibrant economy by reintroducing meritocracy — and not just in government.

As Adrian Wooldridge, author of The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World, recently wrote in Bloomberg Opinion, “Children compete to get into the best nursery schools so that they can get into the best secondary schools and then into the best universities. Examinations regulate the race to get ahead. This examination system, which draws on the tradition of civil service examinations that were administered for more than a thousand years, is now more geared to produce scientists and engineers rather than Confucian officials.”

We need an education system that works for all kids, whatever their background and natural abilities. And by work, I mean maximizes their human potential. And then we can reward that potential by having a society that deeply values achievement. But this is also important: Getting the most out of our best and brightest. I am distressed by growing efforts to undermine gifted education programs across America. When California’s Instructional Quality Commission adopted a new mathematics framework in 2021 that urged schools to do away with accelerated math in grades one through 10, it explained the move this way: “We reject ideas of natural gifts and talents.”

Anyone watching the Olympics right now would reject that reasoning. So would most parents watching their children age and develop. Kids with exceptional abilities in chess, basketball, piano, or ballet stand to benefit from exceptionally challenging instruction. And the same goes for kids with exceptional abilities in poetry, calculus, or chemistry. Finding and nurturing the academically gifted should not be controversial.

A history lesson from France about the importance of brainiacs

The following bit of economic history is relevant to this discussion (and kind of cool, too): The intellectually curious of 18th century France didn’t have Wikipedia, of course. Instead, the salons of such knowledge-seekers contained a different sort of collaborative and curated collection of contributions on all matter of subjects: history, literature, mathematics, mechanical arts, philosophy, science, theology, and more. The Encyclopédie, Ou Dictionnaire Raisonné Des Sciences, Des Arts Et Des Métiers (Encyclopaedia, or Classified Dictionary of Sciences, Arts, and Trades), co-edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert, was the reference book of the Enlightenment. The Encyclopédie represented an important early effort to widely diffuse empirically-derived knowledge into a superstitious world.

Helpfully for economists Mara P. Squicciarini and Nico Voigtländer, one of the publishers secretly kept a list of Encyclopédie booksellers, including their location and how many subscription sets they purchased for their customers. That bit of secret info allowed Squicciarini and Voigtländer to use Encyclopédie subscriptions as a way of determining the density of “knowledge elites.” And with that data in hand, the researchers were able to differentiate between upper-tail knowledge in different cities and that of average worker skills (as represented by schooling and literacy rates). Their key finding from “Human Capital and Industrialization: Evidence from the Age of Enlightenment” (bold by me):

We show that subscriber density is a strong predictor of city growth after the onset of French industrialization. Alternative measures of development such as soldier height, disposable income, and industrial activity confirm this pattern. Initial literacy levels, on the other hand, are associated with development in the cross-section, but they do not predict growth. Finally, by joining data on British patents with a large French firm survey from the 1840s, we shed light on the mechanism: upper-tail knowledge raised productivity in innovative industrial technology.

In other words, regions with lots of “knowledge elite” Frenchman were able to turn technological invention into useful industrial innovation by employing lots of smarter-than-average workers. Again, from the Squicciarini and Voigtländer paper:

Our results have important implications for economic development: while improvements in basic schooling raise wages, greater worker skills alone are not sufficient for industrial takeoff. Instead, upper-tail skills — even if confined to a small elite — are crucial, fostering growth via the innovation and diffusion of modern technology. In this respect, our findings resemble those in today’s economies, where the existence of a social class with high education is crucial for development, entrepreneurial skills matter beyond those of workers, and scientific education is key.

So, if the “upper-tail skills” of a knowledge elite are economically important, then it’s important that they get the proper and appropriate instruction at the very start, not just in college. And one key tool is gifted classes. And while there have been equity concerns about these classes, the research suggests just how valuable they can be for minority and low-income students.

Keep gifted classrooms, create more of them, and then improve them

In the 2014 paper “Does Gifted Education Work? For Which Students?” David Card and Laura Giuliano find that full-time classes for gifted students have large positive effects on non-gifted high achievers in those classes — especially on the reading and math scores of low-income high achievers. The authors conclude that “a separate classroom in every school for the top-performing students could significantly boost the performance of [these] students in even the poorest neighborhoods.”

Granted: These classes need to be more effective. A 2019 survey of 2,000 schools found most gifted programs focus on developing critical and creative thinking skills along with “enrichment” activities, projects, and games rather than advanced instruction. Less important, unfortunately: accelerated instruction in mathematics and language arts.

As my AEI colleague Charles Murray writes in his 2008 book Real Education:

Let gifted children go as fast as they can. If a third-grader is reading at the sixth-grade level, give that child sixth-grade reading. If a third-grader can do math at the sixth-grade level, give that child sixth-grade mathematics. It is a solution that should be welcomed by every reader who can remember sitting in elementary school surreptitiously reading a book while the teacher was teaching things to the rest of the class that you already knew. . . . Academically gifted children do well when they are given a curriculum that is complex, accelerated, and challenging, and when they have teachers with high expectations. Academically gifted children do best when they are with peers who share their interests and who do not tease them for being nerds.

Indeed, my AEI colleague and education scholar Rick Hess notes that the bulk of the research suggests that acceleration, not enrichment, is the most promising way to serve gifted students. Policymakers would be wise to revisit of main findings of a 2004 education report from Nicholas Colangelo, Susan G. Assouline, Miraca U. M. Gross, especially this conclusion: “Acceleration is the most effective curriculum intervention for gifted children.” And this one, too: “Radical acceleration (acceleration by two or more years) is effective academically and socially for highly gifted students.” Faster, please, you know?

So how to create a more acceleration-focused education system? Hess highlights a number of key policies, including preparing more teachers — through recruitment, training, and pay — to teach gifted students. School systems should expand the International Baccalaureate programs, Advanced Placement courses, K–8 gifted offerings, and “high-caliber opportunities” in areas like robotics or music — and make sure all kids get considered for such programs and classes. We owe those students and future generations of Americans no less.

5QQ

❓❓❓❓❓ Five Quick Questions for . . . policy and politics commentator Matthew Yglesias

Matthew Yglesias is a blogger, journalist, and podcaster who currently writes the Slow Boring newsletter. Previously he was a senior correspondent focused on politics and economic policy at Vox, which he co-founded with Ezra Klein and Melissa Bell in 2014. I highly recommend Matt’s 2020 book, One Billion Americans: The Case for Thinking Bigger.

1/ You agreed with Ezra Klein’s case for supply-side progressivism but “didn’t really love the framing. Progressives should care about these supply-side issues, but so should conservatives.” What are the biggest obstacles to pro-abundance policies on the right?

I think identity politics is a major impediment to abundance on the right. In New York State, for example, the new governor Kathy Hochul has put forward a nice plan to relax regulation of the housing sector in the suburban parts of the state. That prompted a furious backlash first from Nassau County's new Republican executive and then from the GOP caucus in the State Assembly. They are construing single-family zoning as a pillar of American suburbanism rather than as a costly regulation. And you saw that transformation on this exact topic in the Trump administration, that started with Ben Carson saying we should all be YIMBYs and ended with Trump saying that Cory Booker wants to abolish the suburbs — by which he meant relax land use regulations.

In recent years, a lot of conservatives have also become more hostile to trade and especially to immigration.

More broadly the populist turn on the right is just very heavily influenced by nostalgia politics (make America great again) of the sort that I recall as having been a pretty distinctively left-coded thing fifteen or twenty years ago. But when you turn into the party that's primarily supported by older and less-educated people, you tend to get invested in a backward-looking worldview.

2/ What is the "great energy diet" and how can we redirect environmental concerns to an energy-abundance agenda?

There was obviously a tremendous disruption to world oil supplies in the 1970s, and it roughly coincided with a growing appreciation of the fact that when you burn stuff that sends a lot of soot and smog into the sky which causes a lot of health and other problems down the road.

Those are two very good reasons to try to burn less coal and oil, and so for the past generation or two per capita energy consumption in the United States has really flattened out. That's really a big change from how things played out over the previous 100–150 years or so when a huge theme of innovation was "how can we use our powerful energy-production technologies to do more and more work?" That's how you got the steam engine and the railroad and electrified factories and electric lights and internal combustion engines and household appliances — you find ways to accomplish things by consuming more and more energy. For the past fifty years so much of the innovation imperative has been to do the opposite, to get from Point A to Point B while consuming less fuel rather than figuring out how to get there faster.

The good news is that we now have at hand several good ways of generating energy that don't create much pollution and aren't subject to the control of questionable foreign powers. And then in advanced nuclear and advanced geothermal we have two more promising candidates for clean energy that could potentially be more space-efficient and convenient than solar and wind. So my hope is that we can plow forward with those technologies, get off the energy diet, and start returning to the pattern of doing new more energy-intensive things like vertical farming, water desalination, and direct air capture of carbon dioxide to solve major problems.

3) How could a more populous America accelerate technological progress and economic growth?

There are all these little microeconomic studies that try to show the impact on the wages of such-and-such kind of people in such-and-such a geography if such-and-such kind of immigrants show up. That's an interesting question, and those studies generally show positive results. But they also really miss the forest for the trees. What was the wage impact of Katalin Kariko coming to the United States to pioneer mRNA technology? It's incalculable and you could say the same for any number of foreign-born scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs.

But of course that same magic is true of native-born people as well. What if Steve Jobs had just never been born? That's a sadder, poorer world. Of course most of us do not get to change the world on the level of a Jobs or a Kariko. The point, though, is we're not living in a Malthusian economy where your kids' food comes out of my kid's mouth. We're mostly performing services for each other, and our prosperity is being driven by a mix of big ideas and small incremental optimizations — and both of those scale up. When you have more people, you have more inventions. And when you have more inventions, everyone benefits.

4/ Looking back at the 2020s from the year 2030, do you think economic/productivity growth will show a marked acceleration from the 2000s and 2010s, the same, or slower?

I do expect some acceleration. The big reason here is that I think the high pressure economy that's been bequeathed to us by Steve Mnuchin, Nancy Pelosi, and Jay Powell has reshaped political debate for the better. With job openings high, unemployment low, and inflation on the top of everybody's mind for the first time in my career, politicians aren't obsessed with "creating jobs." It's good, of course, for people to have jobs. I am pro-jobs.

But the rhetoric and logic of "creating jobs" often leads in the direction of cheerleading for inefficiency. We're now in a world where the labor market is not depressed and people are talking about supply constraints. A decade ago, the idea of self-driving trucks was seen primarily as a threat to people's employment. Today, I think we'd see it as a partial solution to a lot of pressing problems in the logistics side of the economy. Of course wishing for self-driving trucks doesn't make them real. But shifting to a political economy paradigm where efficiency is welcomed rather than feared is, I think, a necessary precondition for a growth acceleration and I think it's something that we finally have in place. Older politicians who cut their teeth on the weak labor market of the first 20 years of the 21st century may be a little slow to catch up in some regards, but I think even as the newer cohort has lots of partisan fights and other kinds of disagreements there is going to be some unity around the importance of raising productivity and that will be important.

5/ Is there a tv show or film that really represents the sort of economic thinking you value or makes good economic points?

I've just always been taken with the optimistic, humane, utopianism of Star Trek: The Next Generation. I don't think it's necessarily a very realistic depiction of the future. But it's unusual in an appealing way in that it depicts a more technologically advanced future society as also more politically and morally advanced, and consequently just generally better off. There are dark sides and pitfalls to some of Trek's tech (especially the damn holodeck) but on net it's all clearly good.

More recently I've been watching the Boba Fett show on Disney+ which is definitely good in its own way. But it's also a striking reminder of how weird the Star Wars economy is — they have all these droids and hyperdrive ships but living standards seem really low. On TNG it's not just that Captain Picard is commanding a good ship, most of the places they go whether it's a nice shiny star base or the YIMBYfied version of San Francisco that hosts Starfleet Headquarters seem like they are benefitting from the wide dispersal of technology and prosperity.

Micro Reads

🌟 DeepMind Has Trained an AI to Control Nuclear Fusion - Amit Katwala, Wired | AI isn’t just about a job-replacing automation, although it’s often treated that way in the media. (Well, that and Terminator-type scenarios.) The flaw in that cramp, constrained vision is made obvious by this important advance. DeepMind, the AI firm backed by Google parent company Alphabet, has developed a deep reinforcement learning system that can autonomously control the fiery plasma inside a tokamak nuclear fusion reactor. From the piece:

In stars, which are also powered by fusion, the sheer gravitational mass is enough to pull hydrogen atoms together and overcome their opposing charges. On Earth, scientists instead use powerful magnetic coils to confine the nuclear fusion reaction, nudging it into the desired position and shaping it like a potter manipulating clay on a wheel. The coils have to be carefully controlled to prevent the plasma from touching the sides of the vessel: this can damage the walls and slow down the fusion reaction. .. But every time researchers want to change the configuration of the plasma and try out different shapes that may yield more power or a cleaner plasma, it necessitates a huge amount of engineering and design work. .. A paper published in the journal Nature describes how researchers from the two groups taught a deep reinforcement learning system to control the 19 magnetic coils inside TCV, the variable-configuration tokamak at the Swiss Plasma Center, which is used to carry out research that will inform the design of bigger fusion reactors in the future.

🏎 Artificial intelligence beats top human players in popular racing game - NPR | Top human gamers competed against an AI agent that learned to drive around the track in just one hour. Four more hours was enough to become as good as the average human driver, and in one to two days it matched the top 1 percent of players. The experiment’s results point to real-world development possibilities for autonomous vehicles. Said a Stanford engineering professor not involved with the study: “It's not as if you can simply take the results of this paper and say, great, I'm going to try it on an autonomous vehicle tomorrow. But I really do think it's an eye-opener for people who develop autonomous vehicles to just sit back and say, well, maybe we need to keep an open mind about the extent of possibilities here with AI.”

🌐 The Technology That’s Helping Companies Thrive Amid the Supply-Chain Chaos - Christopher Mims, WSJ | Entrepreneurs are investing in tech innovations to solve the problems closing supply chains. They’re looking beyond just AI fixes or using more robots in warehouses. Flexible warehouse management systems and inventory trackers, storing goods closer to consumers, and making new hires more productive are key. Investment in tech-focused supply-chain companies totaled $24.3 billion in the first nine months of last year, almost 60 percent higher than the total for all of 2020. Inspiration is found in everything from ant colonies to misshapen food.

🚀 SpaceX’s monstrous, dirt-cheap Starship may transform space travel - The Economist | In addition to the snazzy chart below, the piece is a good explainer on the capabilities of this amazing machine and its potential business and science impact: ‘Mr Musk has talked of eventually building a fleet of Starships. If each were indeed launching several times a day, that would give SpaceX the ability to lug a million tonnes of stuff into orbit each year. BryceTech reckons that, in 2021, the world managed 750 tonnes. What you might do with all that capacity (other than supplying a future Mars colony) is another question.”

⚙ The Rise of the Engineer: Inventing the Professional Inventor During the Industrial Revolution - W. Walker Hanlon (Northwestern University), NBER | Why didn’t the burst of technological progress during the Industrial Revolution fade as previous accelerations had. Hanlon provides evidence that — among other factors such as increasing stock of human capital, the inducements created by an expanding market, the influence of Enlightenment thinking, or the protections provided by the institutional environment — there was a change in the process of innovation that helped sustain forward movement: “the professionalization of invention and design work through the emergence of the engineering profession.” One cool technique used by Hanlon is an examination of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, which revealed “a dramatic increase in the share of engineers among the noteworthy Britons beginning in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. By the middle of the nineteenth century, engineers made up around 20% of all noteworthy individuals associated with science or technology, and over 2% of all of those who merited an ODNB biography.”

⏩ Interview: Alec Stapp and Caleb Watney of the Institute for Progress - Noah Smith, Noahpinion | A wide-ranging chat with Alec Stapp and Caleb Watney (both formerly of the Progressive Policy Institute) who have started a new DC-based think tank called the Institute for Progress. Its mission: "accelerate scientific, technological, and industrial progress while safeguarding humanity’s future," as Watney puts it. The think tank aims to be the flagship institution of the emerging "New Industrialist movement" that hopes to combat NIMBYism and reverse the tech progress stagnation of the past half century.

🚀 Starship Animation- SpaceX | This stirring bit of animation, which Elon Musk showed at his recent Starship presentation, shows a lot more than how the giant rocket works. It gives a feel for how a mission to Mars would work — or, rather the colonization of Mars.

Nano Reads

▶ Eric Schmidt creates $125mn fund for ‘hard problems’ in AI research - Madhumita Murgia, FT |

▶ Why Musk’s biggest space gamble is freaking out his competitors - Bryan Bender, Politico |

▶ The Moon should be privatised to help wipe out poverty on Earth, economists say - Kate Plummer, Indy100 |

▶ How big technology systems are slowing innovation - James Bessen, MIT Technology Review |

▶ These Eye Drops Could Replace Your Reading Glasses - Charles Schmidt, Scientific American |

▶ Bill Gates and Chris Sacca invest in energy storage start-up Antora to help heavy industry go green - Catherine Clifford, CNBC |

I’m an Ivy League graduate with a degree in math who teaches Honors math at an urban public high school. I obviously have some belief in the importance of educating top students. Unfortunately, I find that your analysis is pretty weak.

“As does anyone watching these Olympics” is pretty telling. Do believe that the Winter Olympics is a meritocracy? That people of African descent make up 90%+ of the best sprinters in the world but <5% of the best speed skaters or bobsledders? That the country of Nepal (or India?) contains no naturally gifted skiers? That blind spot is really telling about your view into American Education.

I left a selective admissions charter school (one of the best or the best in the city) for two different open enrollment schools, and the top end talent is the SAME at all three places. But results are better for the students who had a more privileged education and upbringing. True commitment to meritocracy requires grappling with the fact that we have massive amounts of incredibly talented people that we under-develop. You can hand-waive and say we need to make things better for all kids, but here are resources trade-offs, and they are happening, and if you aren’t meaningfully engaging with them then you aren’t actually saying anything about meritocracy.

The opponents of gifted programs gain their audience from the true failure of meritocracy. That it selects for whiteness, for parents who had a work schedule to allow them to maintain proper diet and sleep schedules for their children, for people who live in areas with lower levels of air and water pollution, and for people who have had better past educations.

Go to a prep school for a year and an urban high school for a year, compare college admissions, and you’ll see why people don’t believe in our meritocracy.

If you believe in the relevance of cultivating top tier talent, you need to make much stronger argument in favor of redistributing developmental and educational resources more radically than the soft belief in gifted education you suggest here.

"I mean maximizes their human potential"

Yes, that is the idea. But there's a hidden radicalism in that definition: it has to come along with the idea that not all individual students have the same potential. And the consequences of that, for our education system and our society, are vast.