⏸️💨 The pause before the gale

AI’s disruption is arriving slowly, unevenly, and then eventually all at once. And that's OK

My fellow pro-growth/progress/abundance Up Wingers in the USA and around the world:

Americans are worried about artificial intelligence. Surveys find us more anxious than excited about its spread, with six in ten saying the technology is moving too fast. I mean, no wonder when folks are bombarded by headlines declaring a white-collar “bloodbath” is nigh — to be followed next by humanoid robots coming for blue-collar workers. Also not helping: Endless speculation about a trillion-dollar investment bubble ready to go bust.

Along the same lines, this week’s sell-off in software and data stocks has been driven less by earnings news than by investor unease over AI. The catalyst was Anthropic’s Claude Cowork platform, whose new plugins for legal, finance, sales, marketing, and data analysis tasks have revived fears that AI could encroach on parts of the specialized SaaS market — and maybe sooner rather than later.

That reaction looks premature. Corporate customers are unlikely to abandon entrenched software systems overnight, and while growth at many incumbents is slowing, their businesses are not collapsing. Still, the episode is instructive: Anxiety about AI’s eventual impact is proving powerful enough on its own to unsettle markets and amplify broader concerns about severe economic disruption.

A slow burn

Short version: AI is either about to destroy the economy — at least as we know it — or the destruction has already begun. Yet consider the consensus view from a recent panel of experts convened by The New York Times. They calmly sketched a plausible view of the next half decade, one more or less in line with what I have termed the gradualist Acela Corridor Consensus, a view that places great weight on the economic history of important new general-purpose technologies.

In their telling, AI gradually seeps into the economy. It becomes part of office software, logistics planning, compliance checks, and medical administration. Useful, but hardly revolutionary. There’s no mass unemployment. Productivity rises, but mainly inside the minority (though expanding) number of firms willing to thoroughly rethink how work is organized. Entry-level jobs perhaps grow scarcer, routine cognitive tasks are automated, and wages lag productivity for many workers. A world of winners and losers, though it’s unclear who has the edge.

Call it an Engels’ Pause in a minor key — a transition period where a powerful technology is diffusing through the economy but the overall picture looks frustratingly mixed. Then again, people may be less worried about out-of-control superintelligence even amid the occasional AI agent screw-up.

Not even the end of the beginning

Yet within this transitional period, there may well be obvious green shoots of something pretty great happening. For example: In a new research note, I see Morgan Stanley as arguing that AI-driven productivity growth may be nearing an important turning point, as gains shift from simple capital deepening — all that AI investment —to faster total factor productivity, the economist’s term for doing more with the same inputs through better technology, processes, and organization. In short, an economy’s innovativeness.

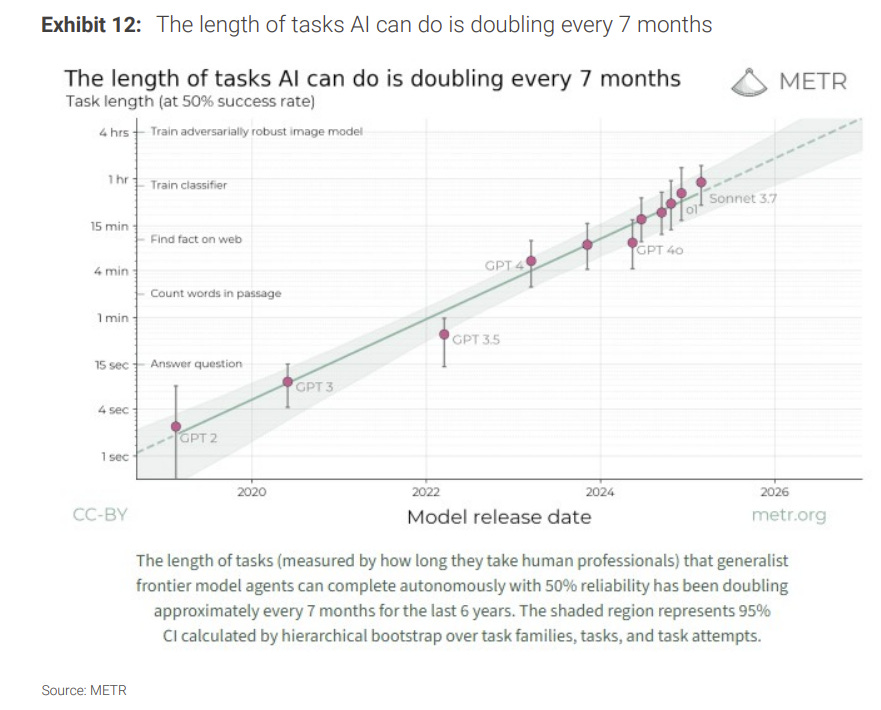

A key metric the bank highlights comes from researchers at METR: the “task horizon,” or how long an AI system can carry out coherent work on its own, which has been doubling roughly every seven months. As AI models move from speeding up isolated tasks to handling longer, integrated chunks of work, the productivity gains begin to compound.

From the report:

AI is also likely to increase productivity. In total, including the productivity benefits, we see AI investment adding 0.41-0.43 pct pt to real GDP growth in 2026-27. As of late 2025, only about 10% of firms report adopting and using AI technology regularly. There’s much further to run, in our view, and we expect the productivity benefits rise in 2026-27.

Significant, in our view, but perhaps not as much as one would expect at first blush based on corporate spending announcements. The risks that we think need to be addressed to build further upside include tariff clarity to help drive US manufacturing, power constraints to power AI, and further capital deepening in the sector to follow traditional investment cycles.

In 2025, we saw AI capabilities increase at a non-linear rate, and we expect this to continue in 2026, with a potential for a range of true “step change” improvements. We are seeing signs of an acceleration in adoption of a wide range of AI tools by businesses, consumers and governments — but the capabilities of AI appear to be accelerating faster than the capability of humans and enterprise workflow to fully harness AI capabilities, implying a need for greater investment into data and systems integration.

If this thesis is broadly right — and, again, it’s in line with the historical diffusion of GPTs — then what the NYT expert consensus describes is a bridge, not the destination. On the far side lies something closer to what the optimists of the accelerationist San Francisco Consensus have been promising: a world of robust worker productivity and wage gains at 1990s levels and beyond, shorter drug-discovery cycles, and reinvented education where AI tutors deliver exceptional personalized instruction at scale — for starters!

Economist Joseph Schumpeter would recognize the pattern. The timing of his gale of creative destruction is inherently unpredictable. But when it fully arrives, no one will doubt its existence and import.

On sale everywhere The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised