🔮 The man who designed a tomorrow that never was. (At least not yet.)

Visual futurist Syd Mead offered a more optimistic and pro-progress vision than seen in his dystopian work on 'Blade Runner' and its '2049' sequel

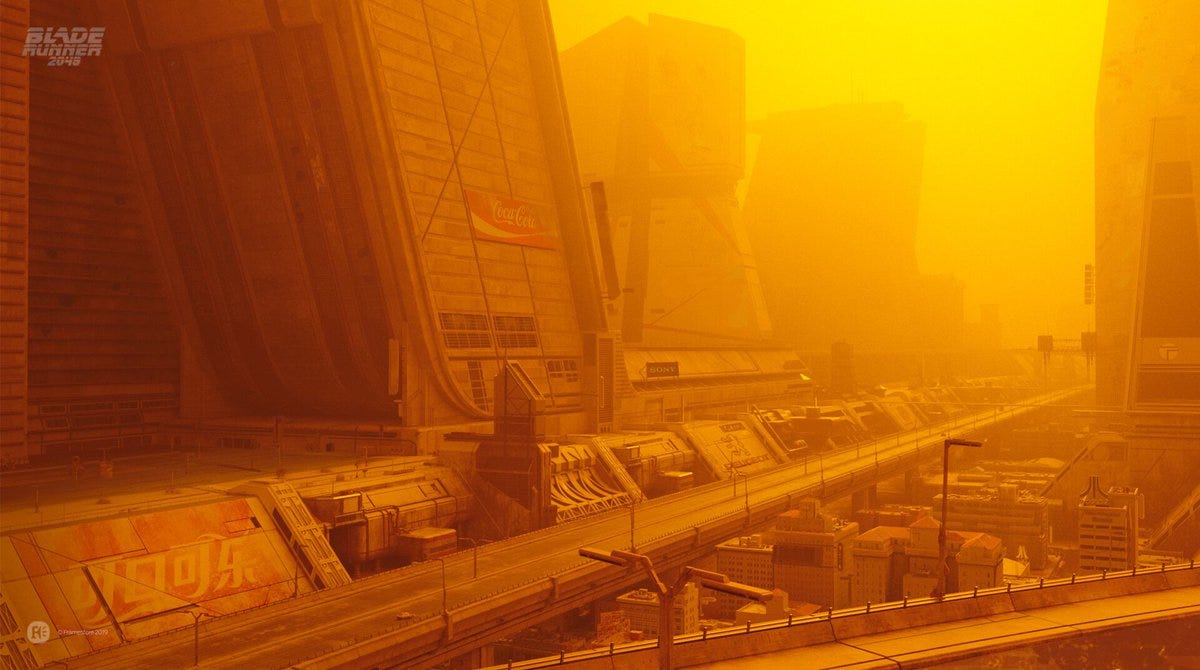

Whatever insights Blade Runner has about the future of humanity and super-smart robots, the 1982 film’s lasting cinematic influence can be found in its unforgettable visualization of a dystopian, near-future Los Angeles. Key to that stunning feat of worldbuilding were the designs of Syd Mead. This includes many of the physical creations in the films — such as the flying “spinner” cars — and the movie’s general look and feel, what became known as “future noir,” described in The Movie Art of Syd Mead (co-written by Mead) as “constant drizzling, no doubt polluted rain, bleak light, the dissonant hum of machines, men, and hawkers, and layer upon layer of cables and abandoned structures … as though whole of Los Angeles was on life support.”

When Denis Villeneuve signed on to direct and worldbuild the sequel, Blade Runner 2049, he knew Mead had to play a role:

I may be wrong, but I think Syd’s traveled in dystopia only once, and it was because of Ridley Scott. Syd’s first drawings were pure, bright, and peaceful, but Ridley wanted his new world to be more claustrophobic and oppressive. And Syd dived into the darkness. As I was creating the universe of Blade Runner 2049, I realized only one person could reimagine the city of Las Vegas and give it the magnetism it needed to be worthy of Blade Runner’s dystopian landscape. So I asked the master to go back to the future for me. He came back with stunning images. I never thought Las Vegas could be as pure, beautiful, devoid of cynicism. I didn’t ask Syd to go darker. I needed this powerful beauty, maybe for my own sake.

Villeneuve’s comments highlight the obvious irony of Mead’s artistic career and legacy. His 2020 death at 86 from lymphoma was followed by numerous obituaries that understandably gave prominence to his dark Blade Runner work. But the best of those, usually several paragraphs deep, correctly made it clear that Mead was hardly the Down Wing gloomster that Scott asked him to be. At his core, Mead was an optimistic techno-futurist. Inspired as a child by early science fiction such as Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, he headed to art school after an early 1950s stint in the US Army, graduating from L.A.’s Art Center School in 1959. Then came his corporate career as an industrial designer and illustrator for companies such as Ford, U.S. Steel, and Philips Electronics, first as an employee and then through his own studio. Mead’s first work for film was designing the V’ger entity for Star Trek: The Motion Picture in 1979.

It was in the pre-Hollywood part of Mead’s life that he became known for fantastical-yet-practical design work. One favorite set of illustrations of mine are these promotional works he did for U.S. Steel in 1959:

This from “What Died with John Portman and Syd Mead, America's Last Urban Optimists?” by Colin Marshall for Archinect:

It seems to have been something of a blue-sky assignment, in response to which the young Mead produced, rather than utilitarian images of panels and beams, hypnotically glossy and colorful but nevertheless functional-looking visions of the world to come: impossibly low, aerodynamic sedans, one complete with gullwing doors, a chauffeur, and a giant lynx; a glass-walled suburban cross between a Case Study house and a moon base; even The Empire Strikes Back-style walkers making their hulking, deliberate way through the snow. And when Mead had occasion to render a city (or even as un-urban an environment as the Grand Canyon), he never failed to include megastructures: skyscrapers not just taller than any yet built in reality, but much more expansive as well, hinting at whole other cities hidden behind their walls.

It was these sort of lush, imaginative images of a postwar Golden Age of rapid economic growth and tech progress never ended that drew Hollywood to Mead. Unfortunately, Hollywood never chose to build upon Mead’s optimistic vision. Instead, we got Blade Runner (which is not to detract from its greatness as a film), which has played a huge role in our societal imagining of a technologically advanced tomorrow that helped ruin the world rather than fix it. Marshall notes (as Villeneuve also suggests) that Mead “in life distanced himself from the grim cinematic vision his work enriched.” And he was hardly alone. “Plenty of sci-fi creators have publicly bemoaned their genre’s overly dark turn and its impact on our societal ambition,” I wrote back in 2021.

Let’s set aside Blade Runner. Mead also contributed visual design work to the 2013 film Elysium where the rich live on an orbital space station above a polluted, impoverished, and overpopulated Earth. The habitat’s design is obviously inspired by Meads’ early work. But rather than an inspiring film about what humanity can accomplish, Elysium only provides more 1970s-style eco-pessimism along with a helping of 21st century “late capitalism” theory.

And here, again, is why all of this matters: Just as Up Wing progress can inspire culture — it was pretty easy for those early Disneyland imagineers to build Tomorrowland as the Space Age and Atomic Age were starting — culture can support growth and innovation. That, both by inspiring technologists and entrepreneurs such as Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, but also by giving broader society the confidence that the inevitable disruption caused by progress will be worth it. In this way, technological progress, as well as pro-progress politics, is downstream from culture — both in terms of what we value today and how we imagine tomorrow. And that stream has been polluted with caution and pessimism for a half century, thanks in part to Hollywood.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. I’ve been highlighting films and television shows that are both future-optimistic and tech-solutionist, as well as compelling entertainment. (And not just the Star Trek franchise.) One wonders what Mead might have produced if a filmmaker embraced his Up Wing optimism. Actually, we don’t have to wonder. The 2015 film Tomorrowland, directed by Brad Bird, does just that.

As the foreword to The Movie Art of Syd Mead puts it: “Mead’s images — confident, manifestly manmade, and culturally unapologetic — represent a technology-positive and aware worldview … [with] a powerful ability to summon heroic, even idealistic emotions.” More of that, please. Just compare the L.A. of Blade Runner to this other Mead vision of the city:

Maybe we’ll see something like this in Blade Runner 2079.

Micro Reads

▶ Russia Says It Will Quit the International Space Station After 2024 - Kenneth Chang and Ivan Nechepurenko, NYT | If Russia follows through, it could accelerate the end of a project that NASA has spent about $100 billion on over the last quarter-century and set off a scrambling over what to do next. The space station, a partnership with Russia that also involves Canada, Europe and Japan, is key to studying the effects of weightlessness and radiation on human health — research that is still unfinished but needed before astronauts embark on longer voyages to Mars. It has also turned into a proving ground for commercial use of space, including visits by wealthy private citizens and the manufacturing of high-purity optical fibers.

▶ White House pushes for next generation COVID vaccines - Medical Xpress - The White House on Tuesday held a summit with vaccine makers and scientists as it pushed for "next generation" COVID-19 vaccines that offer broader and more durable protection against the virus. … Nasal vaccines are being tested in mice, where they have shown promise, while vaccine developers Pfizer and BioNTech have announced they will work towards trials for universal coronavirus vaccines. … In a commentary for Science magazine, scientists Eric Topol and Akiko Iwasaki argued that a new funding program for next generation vaccines was needed, along the lines of Operation Warp Speed, which funneled $10 billion into vaccine development early in the pandemic.

▶ James Lovelock obituary: Scientist, environmentalist, inventor and exponent of the Gaia theory of the Earth as a self-regulating system - Pearce Wright and Tim Radford, The Guardian | Unlike most environmentalists, Lovelock favoured nuclear energy. “Some time in the next century, when the adverse effects of climate change begin to bite, people will look back in anger at those who now so foolishly continue to pollute by burning fossil fuel instead of accepting the beneficence of nuclear power. Is our distrust of nuclear power and genetically modified food soundly based?” he asked.

▶ A day in the life of a Chinese robotaxi driver - Zeyi Yang, MIT Tech Review | I would get afraid when I first started this job because I was not the one controlling it. Like when it was making a turn, maybe I [as a driver] would turn this wide, but it would turn that wide. The car will follow the legally required paths, but when we are driving ourselves, we may occasionally cut corners or cross the solid line. So the paths we would take are different. …I couldn’t get used to it in the beginning. After a day’s work was over and when I got back in my own car, I would treat it as if it were a self-driving car. Sometimes, when I got to my car I instinctively went for the passenger seat. Or when I was driving, I would expect the car to brake by itself. And then I realized that’s not right. It’s me [driving this car.] But I got used to it after a few times, and then it’s back to normal.

▶ How bad will the global food crisis get? - Chelsea Bruce-Lockhart and Emiko Terazono, FT | Not everyone thinks the crisis will become more severe. Earlier this month, Morgan Stanley issued an optimistic report on the future of food prices, suggesting increases in 2023 will be lower than expected. Increased grain production by farmers, including in Ukraine as tensions ease, will temper food inflation, the report said.