🚀 'Over the long term, you cannot have a society that views technological progress as making life worse'

Economist Michael Strain interviews me(!) about my new book, 'The Conservative Futurist: How to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised'

I was recently inteviewed about my new book, The Conservative Futurist: How to Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised, by Michael Strain, director of Economic Policy Studies my employer, the American Enterprise Institute. I think it was a good chat, and I hope you think so, too.

Michael Strain: I was at the Air and Space Museum recently, and I found myself thinking about your book. Right now, when you walk into the Air and Space Museum, the first thing you see is the original model for the Starship Enterprise created for the 1960s sci-fi television show, Star Trek. Lots of quotes from Gene Roddenberry, who created Star Trek. That’s right at the front door.

And then when you walk into the museum, you see, of course, lots of exhibits about mankind’s pioneering journey of exploration that began with the Wright brothers, and that continued into the space program. And when you look at what we were able to accomplish in those six decades, from when the Wright brothers first took off on an airplane, using bicycle technology, to the point where President Kennedy declared that we would put a man on the moon, to the point that we actually did have astronauts walking on the moon, it’s an extraordinary journey.

And you write about that in the book. You argue that very shortly after Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, we stopped. Culturally, we stopped. Public policy decelerated our ability to advance in that fashion. And the private sector pulled back.

What was it that created a cultural moment where optimistic science fiction was commercially successful and extremely popular? Government put its shoulder into economic dynamism, into innovation, into scientific progress and achievement. What happened that allowed the private sector to embrace all of that? Why was that era so important? What was the magic sauce?

James Pethokoukis: I think the simplest answer is that culture reflected what seemed to be happening in the real world. Perhaps the most important bit of 20th-century futurism, was the early ’60s Jetsons cartoon show. And the makers of that show did not think that they were engaging in science fantasy. They thought their show was reflecting the current trends at the time, that it was actually the kind of future we were headed for.

And immediately after World War II, there was quite a bit of pessimism about the future. You had famous economists saying that we were going to go back into a great depression. And that didn’t happen. The economy accelerated. We had the beginning of an atomic age, a space age. So just to look around, it seemed as if there was something new being invented every day. And that was absolutely reflected in the culture at the time, in science fiction, I mentioned Jetsons, but also Star Trek, even a movie like 2001: A Space Odyssey.

So you had the culture and the economy firing on all cylinders together. And then that changed. In 1970, there was a book that came out, it was called Future Shock, by Alvin Toffler. And in that book, which was a New York Times bestseller, Toffler predicted that economic growth and technological progress was going to be so rapid, it would just drive us all crazy. So the conundrum was: How do we deal with such rapid progress? So that was sort of the expectation. And the true future shock was that we didn’t get that. And several decades later, Toffler told Wired magazine, , “Well, the economists really tricked me. They got it all wrong.” We thought we had the growth problem licked, but turns out we didn’t. [The postwar optimists] thought that the rapid growth in productivity growth, technological progress that we saw in the ’50s and ’60s, would not just continue, but it would accelerate. In fact, it decelerated.

And it’s sort of a chicken or the egg, what came first, the deceleration or the pessimism? I tend to go with the pessimism. It’s not uncommon, as a country gets richer, that people begin to focus a lot more on the downsides of economic growth, the environmental downsides. So I think it was always likely, if not certain, that we were going to have an environmental movement. But then you also had a lot more coming in the ’50s about radiation dangers in Hiroshima. We had a lot of books come out like Silent Spring, which really focused on the economic downsides of growth.

And then you also had the Vietnam War, which really confirmed the worst fears of the environmental movement at the time, that the combination of government, and the military, big business, were ruining the planet. And to them, napalm and Agent Orange were no different than the poisons business was releasing into society. But culturally, everything that could go wrong, went wrong. And then we had an actual, measurable deceleration in growth. Which undercuts, I think, the entire sort of pro-progress, future-optimistic vibe of the era.

Strain: So I want to dig a little more into this, because one of the things about this book that I like the most, and that I think is a really important contribution to the public debate, is that it situates economic outcomes in a cultural context. And economists are very good at economic outcomes, they’re not so great at culture. Cultural analysts are really good at cultural analysis, they’re not so great at economics. And I think the book does a very good job of kind of blending the two and recognizing that people kind of live life in a market society, in a culture. And that the causal arrow between economic outcomes and cultural outcomes runs in both directions. It sounds like you think that the kind of cultural pessimism predated the downshift in economic productivity.

So what do you think led to the cultural pessimism? Was it something as simple as, “Okay, we’ve done The Jetsons. Okay, we’ve done Star Trek. Wow, this is a little utopian. You know, can we do something different?” Was it, as you said, a kind of growing awareness that there are some downsides to some of the innovation that we came up with in the ’60s? Or was it just that the ‘70s were a bad decade? Extremely high inflation, coming off the heels of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., coming off the heels of the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, coming off of a time of substantial social unrest and disruption. Lots of crime in cities. This sense that things are kind of a little bit out of control culturally, instability in politics, instability in society. The 1973 Arab oil embargo people have to wait in lines to fill their car up with gas. Tons of high inflation, the government can’t get inflation under control. And maybe Gene Roddenberry’s vision for a future that was as bright as Star Trek painted, or The Jetsons’ vision of a future that was as kind of sparkly as it was, just didn’t make sense.

Over the long term, you cannot have a society that views technological progress as making life worse, that also over the long run is going to tolerate the disruption that comes with technological change and economic growth

Pethokoukis: One reason I wrote the book was a paper I read by an economist from Yale about what he saw as the decline in futuristic thinking or forward thinking in the United States. And he looked at two bits of evidence. One, the federal budget moving into deficit and long-term budget deficits. And he looked at less spending on infrastructure. And so the theory there is that both those things indicate a society that was thinking less about the long term. And he asked that question, like, what happened to us? And he mentioned many of the things you just mentioned. And he didn’t think that was an answerable question, that we had no way of figuring it out.

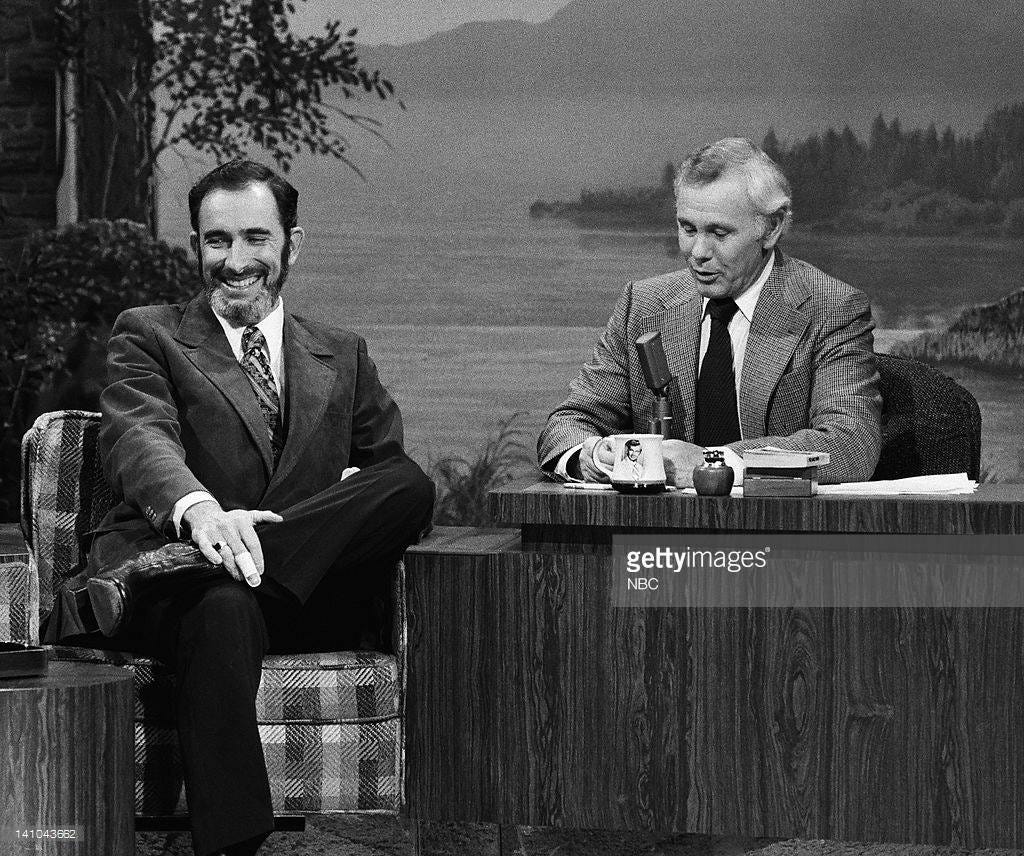

But I take my best shot at it. I certainly think you have sort of this economic downshift. Super important. You have all the other sort of societal problems. But I don’t think it is insignificant what Hollywood believed about the world and the future, and what they were being told by experts: the future just didn’t look very bright, that we were rapidly using up all the resources on the Earth. That there were too many people on the Earth. One example: Paul Ehrlich, who wrote The Population Bomb, which made lots of predictions about overpopulation. He was on The Tonight Show, which back then was hosted by Johnny Carson. And everybody watched The Tonight Show. So this is a biologist from Stanford with a message of gloom. And he was on The Tonight Show over 20 times preaching this exact message.

I think one example was the nuclear power industry, where even in the early ’70s, you had people criticize nuclear power as contributing to using up all the resources of the Earth. And you had Three Mile Island, which really put the industry in mothballs.

And just when you might think that this is a ’70s phenomenon, I see what’s going on with AI, when we had this perhaps really important breakthrough in artificial intelligence last November, and we all got to enjoy it for about 15 minutes talking about, gee, what can it do? How might it make the world better? And then immediately, we started talking about, it’s going to take all the jobs. And then when it gets done taking all the jobs, it’s going to kill us. And we need to have a pause. We need to heavily regulate it. Maybe we need to nationalize these large language models.

So this sort of pervasive gloom, and the news stories about AI, how often have they mentioned The Terminator? While some of you may not have heard of The Jetsons, we’ve all heard of The Terminator. It became the cultural touchstone when people were trying to think about this new technology and what it mean for us.

I think over the long term, you cannot have a society that views technological progress as making life worse, that also over the long run is going to tolerate the disruption that comes with technological change and economic growth. They’re not going to tolerate that, and much less, invest heavily in that, and think hard about how government policy slows innovation, if they think ultimately, all it will do is make our life worse.

Year after year, movie after movie, TV series after TV series, the message is being given that tomorrow will be worse, and we need to retreat. We need to live poorer lives — oh, I’m sorry if you live in a country where you’re already poor, you will never live like the people in the West do today.

Strain: Something I wonder is how much of this is human nature? AI is a good example. You know, here’s a technology that could substantially assist medical science in the creation of new drugs, and vaccines, and therapeutics. A technology that was used in the COVID-19 pandemic to create a vaccine. A technology that is currently being used to track volcanic ash activity and to improve scientists’ understanding of volcanic activity. Volcanic activity, of course, being the most common mass extinction event that occurs on the planet. Scientists using this technology to better track the paths of asteroids to allow our planet to prepare if there’s an asteroid collision. You know, it seems to me that the odds of AI extending the longevity of the human race are substantially higher than the odds of AI leading to the death of all life on Earth. And yet, that is not the headline. And so, is there something in human nature that leads us to be concerned about the worst-case scenario rather than the median scenario? Something that leads us to be concerned more about the worst-case scenario than the best-case scenario? And if so, why didn’t we have that in the ’50s and ’60s, but we did have it in the ’70s and ’80s?

Pethokoukis: If you go to the Wikipedia page for behavioral economics or cognitive biases, you’re going to find a lot that seem to reinforce the notion that we are sort of hardwired to sort of want the status quo, that we’re hardwired to be cautious, that we feel economic losses more strongly than we feel economic gains.

That’s part of who we are as a society. And I think evolutionary biologists might make the same point. So it is really important that we have a culture that creates images of a future people think would be worth living in.

Again, I think that helps reinforce a policy environment of pro-growth, pro-progress policies. With change will come disruption. And people have to think it’s worth it. If you look at trade, a lot of people think maybe it’s not worth it. That trade between two countries, all it does is really make the United States poorer. So they no longer have that image that maybe they had around the turn of the century, that trade would create more prosperity, it might reduce geopolitical tension. They no longer had that image.

So I think if that’s who we are as a species, then it’s even more damaging when that sort of natural inclination is being reinforced at every step by a culture that says, better safe than sorry. Apple TV+ had this huge star-studded miniseries called Extrapolations, where it looked at the impact of climate change over a number of decades. And if you watched that, you would not know nuclear power even existed. That was never offered as a possible solution. Instead, it just showed humanity getting worse. And by the end, humanity had barely survived. And CEOs were being put on trial for war crimes. I mean, that is just one example. And it was Apple, a lot of big-name stars, big budgets. So that message, I mean, ignoring all the advances we’re seeing with nuclear energy, maybe nuclear fusion.

The fact that especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a lot of European countries began to think a lot harder about keeping reactors open, building new reactors — even Japan, which had a serious meltdown a decade ago, now reembracing nuclear power. None of that was evident in that show. So year after year, movie after movie, TV series after TV series, the message is being given that tomorrow will be worse, and we need to retreat. We need to live poorer lives — oh, I’m sorry if you live in a country where you’re already poor, you will never live like the people in the West do today.

Coming out of World War Two and The Great Depression, there was tons of pessimism. But then the economy started popping, technology started popping. So I think that worked to counter that natural [pessimistic, status-quo bias] inclination.

Strain: So what was different about the ’50s and the ’60s? Why isn’t that what we had been?

Pethokoukis: Well, I think what happened was that, again, in the second sort of the latter half of the Industrial Revolution, people could look around them and see progress. As I mentioned, coming out of World War Two and The Great Depression, there was tons of pessimism. But then the economy started popping, technology started popping. So I think that worked to counter that natural inclination. You didn’t need to be convinced that the world was getting better or more prosperous. You saw it all around you. In fact, the first chapter is a lot about the opening of Disneyland and Tomorrowland. And when they opened up Tomorrowland, they immediately had a problem, in that progress was moving so fast that Tomorrowland didn’t really look particularly futuristic. (The centerpiece of the original Tomorrowland was a rocket which gave a feel for what it’d be like to ride on a commercial rocket in the far-off year of 1986.)

But at the same time that was happening, we had an emerging space program. And Walt Disney began to complain that Tomorrowland began to look like “today-land” or “yesterday-land,” because Tomorrowland just couldn’t keep up with what was actually happening in the real world.

Eventually that changed though. Eventually, the real world stopped creating the sort of advances that inspired the Disneyland Imagineers, and Tomorrowland began to be really viewed as having no connection with what was really going out in the real world. And they had a lot of debates on how should they change Tomorrowland. Maybemake it more like fantasy oriented, and science fiction oriented. And they chose to make it more like, steampunk Jules Verne version.

But originally, it just was so obvious that progress was happening quickly, that we would be living on the Moon and Mars, and we would have nuclear-powered everything. The famous 1964 Futurama exhibit at the 1964 World’s Fair, presented as the obvious next steps for United States, was to have undersea cities, and again, moon colonies, and mile-high skyscrapers. So, again, progress seemed to be moving so rapidly that I think it counteracted that natural inclination for pessimism.

The core of my conservative futurism is that you can be positive about the future, whether you’re on the left or right. It’s a vision that embraces using economic growth and technological progress, to create a better world, to solve big problems. But one that is rooted in human freedom, liberal democracy, market capitalism, and social mobility, being able to climb the ladder.

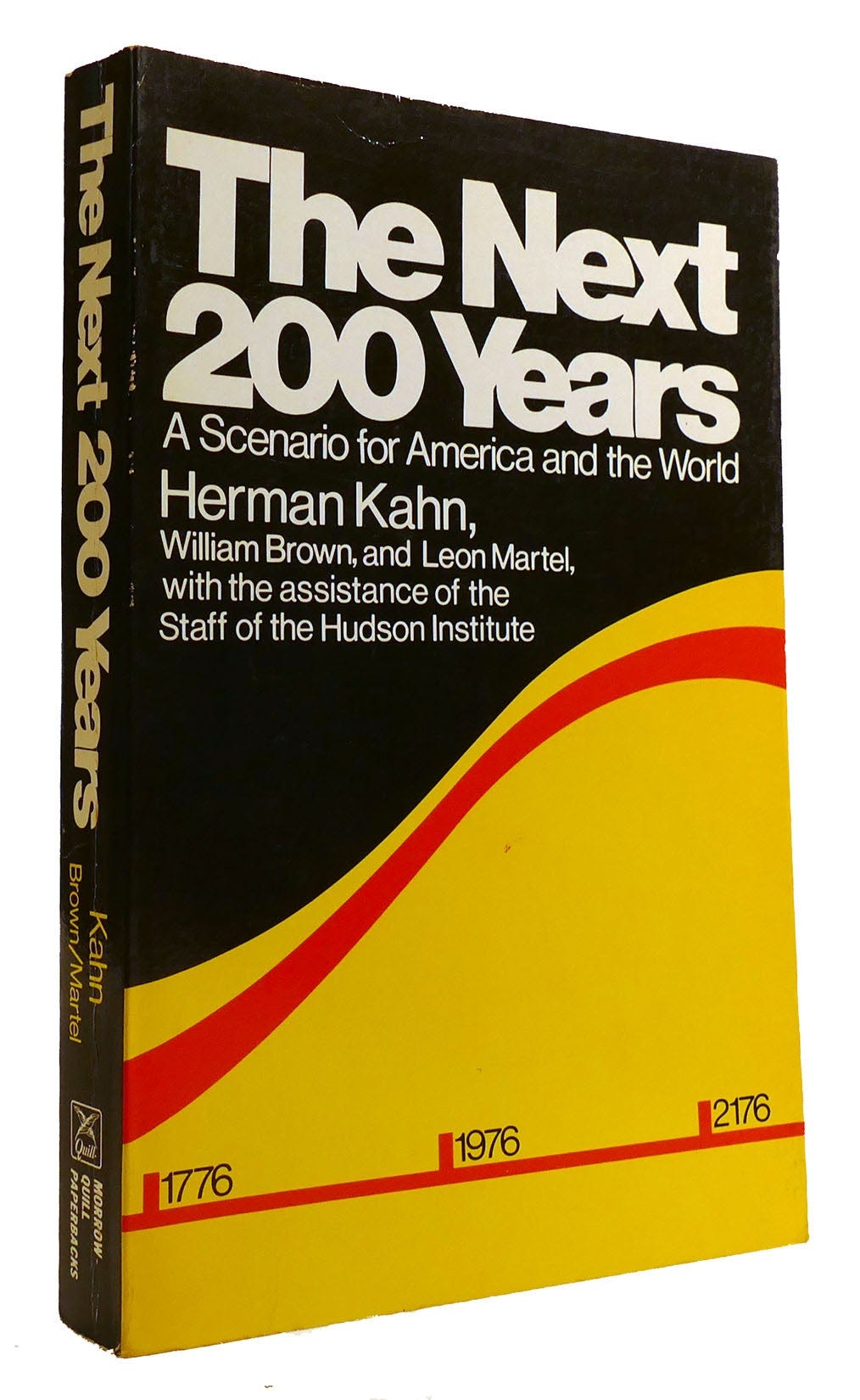

Strain: So, that’s a good segue into something that I wanted to talk about. The book has some great characters in it. Another is Herman Kahn. Do you want to tell the folks a little about Herman Kahn?

Pethokoukis: Herman Kahn was a nuclear war theorist. And if you’ve ever seen the 1960s film, Dr. Strangelove, by Stanley Kubrick, there was a mad scientist who seemed too eager for nuclear war in that film. And he was partially inspired by Herman Kahn, as well as Henry Kissinger.

And before Stanley Kubrick did this film, he had read Herman Kahn’s books, he had met him personally and interviewed him. Kahn was portrayed as sort of this dark figure of Armageddon. And then Kahn had a second act in his career, where, by the 1970s, he really became a futurist, did a lot of scenario planning, was super optimistic about what he called techno-capitalism, what techno-capitalism could produce. And back in the ’70s, he wrote that certainly by now, we would have mastered the solar system. And what’s sort of really interesting is that he is an example of a sort of market-oriented, conservative futurist who when he passed in 1983, Ronald Reagan said, “Herman Kahn was a futurist who was not afraid of the future.” And why it was important to make that description was that by the 1980s, futurists and other people who thought about the future were almost uniformly negative. Again, they saw a world of depleted resources, of overpopulation, eventually of a chaotic climate, though, in the ’70s, it was more new ice age than an Earth that was going to get too hot.

So he really stood out as someone who thought about the future, thought that if we made a few good decisions, and avoided some bad luck, that it could be a future of great abundance and prosperity and peace, built around a core of human freedom. This wasn’t about a future where the Department of the Future in Washington would come up with a bunch of five- and 10-year plans, and accurately predict exactly what the future should look like. He didn’t believe that at all. He thought that human beings empowered to make decisions about their own lives, and businesses and entrepreneurs to be able to be rewarded for their efforts would probably create a pretty fantastic future.

So that is really the core of my conservative futurism, though I think you can be positive about the future, whether you’re on the left or right. It’s a vision that embraces using economic growth and technological progress, to create a better world, to solve big problems. But one that is rooted in human freedom, liberal democracy, market capitalism, and social mobility, being able to climb the ladder. So that’s what the core of my conservative futurism is about. But again, if you think that we can solve problems, that tomorrow doesn’t have to be worse, that we can create a better world, not a utopia, but we can create a better world, then I think, no matter where you are on the spectrum, that you’ll find a lot in this book to read and enjoy.

What’s also interesting is that people who know Kahn from Dr. Strangelove assume that he was really kind of this glowering, dark character. But he was not. He was a really kind of jovial, upbeat guy, who when he looked at the ’70s, and looked even what the ’60s had produced, saw the potential for society. I mean, back in the ’60s, economists didn’t do a lot of long-range economic forecasting. He did, and he was the head of the Hudson Institute think tank in New York State. And their economic forecasts were unbelievable. Not only that we were going to have a forever 1960s, but that we would have an acceleration most likely.

And he was hardly alone. Kahn participated in a great conference in 2018 where they had CEOs and think tankers and [and government officials] and everyone sort of agreed that things were only going to get better. That even though the Vietnam War had begun, and we were starting to see inflation, that we would grow and there would b a long period of sort of good vibes there in the ’50s and ’60s.

And then we saw another taste of that in the late 1990s with the internet boom. We saw again, a lot of very buoyant forecasts about what the future would hold, both from the administration, from the Federal Reserve, and Wall Street. I had kept this one report around for over 20 years from Lehman Brothers, which they wrote in the summer of 1990. They were confident that the productivity and economic boom of the late ’90s would only continue. And that the only problem was just being able to make sure you fully profited from the amazing growth over the next decade. Unfortunately, Lehman Brothers did not even make it another decade because they collapsed during the financial crisis of 2008 through 2009.

So, every once in a while, we’ve had this period of real techno-optimism. And the point of the book is, I want that period again, but I want to say this sustain it, hopefully through better economic policy and a more pro-progress culture.

If a science fiction author today was given that kind of opportunity to be regarded as a public intellectual, it would no doubt be a message of utter gloom that they would be giving to the public.

Strain: Another character is Isaac Asimov. Say a little about Asimov.

Pethokoukis: You know, there was a time when science-fiction authors were highly regarded public intellectuals. It’s hard to even imagine a science fiction author today who is regarded in the same way that Arthur C. Clarke and Asimov were in the 1960s.

And again, during the 1964 World’s Fair, it was very natural that the New York Times would ask Asimov to write a column about what a World’s Fair in 20 years or 40 years might look like. Because he wasn’t just someone who created interesting stories about tomorrow, but they were supposedly rooted in hard science, and it was supposed to be a science fiction of the possible. And in that great 1964 column in the New York Times, he wrote about what the future would be like. And it would be nuclear-powered everything. It would be nuclear-powered appliances, the nuclear-powered cars. And that feeling that we had solved this energy problem as the ultimate general-purpose technology, was pervasive.

And again, I can’t imagine a science fiction author today being held in the same regard as they were in the 1960s. I got a little bit of that in the 1990s with science fiction. But now if you had a science fiction author [write such an essay today], they would no doubt paint a picture of gloom, saying that we had to probably live poorer lives, that we needed to move away from capitalism. Or they would probably say rapacious capitalism, which was destroying the planet. So if a science fiction author today was given that kind of opportunity to be regarded as a public intellectual, it would no doubt be a message of utter gloom that they would be giving to the public.

What if last November, instead of it being OpenAI announcing they had created this really fascinating advance, this chatbot, what instead of it being OpenAI, it had been Alibaba, or Tencent, or some other Chinese company that said, we have made an AI breakthrough, and the United States is several years behind?

Strain: So when I think about what was different about the ’50s and ’60s, I think about the Cold War. And one of the principal motivators behind the American space program was, of course, Sputnik, and that the Soviet Union beat us in space. Do we need an adversary in order to kind of push us further in innovation, in order to push us further in scientific progress? So we need an adversary? Has that been what’s missing?

Pethokoukis: I would like to think that positive images of the future and me pointing out, “Wouldn’t it be great if we already had a universal Coronavirus vaccine back in 2020? And wouldn’t it be great that we already had nuclear reactors and 100 percent clean energy economy,and we wouldn’t be talking about climate change, wouldn’t that be great?” and that would inspire people to think differently about the future, maybe have different economic policies.

The example I like to give is, what if last November, instead of it being OpenAI announcing they had created this really fascinating advance, this chatbot, what instead of it being OpenAI, it had been Alibaba, or Tencent, or some other Chinese company that said, we have made an AI breakthrough, and the United States is several years behind? If everyone is already tired of hearing about AI, we would really be sick of it, because that is literally all we would be talking about, not just what this technology means, but that the US had lost the AI race. And what did we do wrong? And there would be a panic.

And I have no doubt now there’d be all sorts of bills in Congress about how we need to increase funding. There’s a legitimate AI race. So it would be terrifying to think that we were behind, that the United States, the supposed world’s technological leader, had somehow fallen behind. We’re not behind, but yet I think the fear that China somehow has figured out a new way to do technological progress and to grow an economy, I think can be a tailwind for economic policy, for us thinking harder about the innovation impacts of what we do as a country, about our culture. I don’t know if there has to be, but it certainly I think, helps to have sort of a geopolitical nudge. And it used to be the Soviet Union, and now it’s China. I don’t think it hurts.

I focus a lot on economic growth and what it can do for us and bring people out of poverty. But solving huge problems that are existential or very serious in nature, whether it is a pandemic, whether it is being able to deal with the climate without living worse lives, whether it is protecting humanity, and extending it throughout the solar system and beyond.

Michael Strain: Humanity, the human race, is confined to this planet. And that puts our species at significant risk. We could have a big volcano, asteroid could strike. At a minimum, at some point, the sun is going to extinguish itself, and life on Earth will not be sustainable. And so, I think it is a fact, I would say, or at least as close to a fact as you can get without being a fact, that the human race has two potential outcomes. That we have a good run, and that the run ends on this planet. Or that we leave this planet and become an interplanetary civilization. That observation to me is enough to motivate concern about the pace of innovation and the pace of scientific progress. How do you react to that?

James Pethokoukis: I mean, we’ve talked about sort of a lot of pessimistic Hollywood films right up to the present day. And that is sort of the argument from the film Interstellar, by Christopher Nolan. The main character in Interstellar says, “We were born here, we weren’t meant to die here.” … I will point out Armageddon, of course, came out in the ’90s during a very pro-progress era. And it showed, indeed, humanity being able to solve a problem with technology. It’s not a negative movie. I think that is a powerful argument. I think I might have written more about planetary defense, because currently we are no more capable of protecting ourselves on short notice than we’ve ever been. Some of you might remember a meteor strike in Russia, which was captured in a lot of dashboard cams, which was probably the biggest meteor strike since the Tunguska blast in the early 20th century over Siberia. I think we had like 30 minutes of warning.

I think that’s really important, ensuring, and I’m going to sound very Elon Musk-like, you know, sort of the light of intelligence throughout the universe. In the book, I focus a lot on economic growth and what it can do for us and bring people out of poverty. But solving huge problems that are existential or very serious in nature, whether it is a pandemic, whether it is being able to deal with the climate without living worse lives, whether it is protecting humanity, and extending it throughout the solar system and beyond.

I don’t think those are insignificant reasons to be in favor of progress and economic growth, and sort of the degrowth movement that’s out there. Perhaps they just don’t think it’s very important that humanity survives. So that’s not really a huge factor with them. In fact, they’re very much from the extension of the 1970s environmental movement, which really began to look at humanity as just another life form on the Earth, is making the Earth worse, is a cancer on the Earth. So it doesn’t surprise me that the environmentalists of the kind who only really view humanity as making the Earth a worse place, don’t really focus too much on these sorts of existential risks. Because for them, what’s really the downside?

Now on sale absoutely everywhere:

My new book The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised