Nuclear fusion breakthrough: Will star power fuel a Roaring Twenty-First Century economy?

Also: Environmental reviews leave America stuck in regulatory traffic

“The great thing about space exploration is that we don’t know what its payoff will be. This symbolizes the American civilization. The people who settled America had no idea what the payoff would be. They settled it before they explored it.” - historian Daniel J. Boorstin

In This Issue:

The Long Read: Nuclear fusion: Will star power fuel a Roaring Twenty-First Century?

The Short Read: Environmental reviews continue to slow and hamper America’s ability to build

The Micro Reads: Space solar power, the future of driverless cars, diagnosing dementia with AI, and more. . .

The Long Read

🌟Nuclear fusion: Will star power fuel a Roaring Twenty-First Century?

Now here’s an encouraging headline, via The New York Times: “Laser Fusion Experiment Unleashes an Energetic Burst of Optimism.” (More on this in a bit.) As loyal Faster, Please! subscribers know by now, I love the notion and nomenclature of a “New Roaring Twenties.” That hopeful phrase suggests America is entering not just a period of renewed optimism about the future, but also a period of rapid, innovation-driven productivity and economic growth.

The historical parallel is obvious: Shortly after the 1918 "Spanish Flu" departed, the roaring 1920s arrived. History may not rhyme, but even an echo of that powerful post-pandemic boom — real GDP grew by nearly 5 percent annually from 1921 through 1929 and total factor productivity growth surged — would be most welcome following years of slow growth, stagnant productivity, and, of course, the global COVID-19 outbreak.

But I want more than just a boom. I want a lengthy period of sustained acceleration, so much so that rather than thinking of it as a boom, it becomes our new baseline expectation. And for that to happen, more will be required than just a work-from-home productivity boost and increased use of e-commerce. After all, there were plenty of significant innovations in the 1920s. Among them: liquid-fueled rockets, penicillin, and television.

But the key innovation behind that decade’s productivity surge, as described by economist Alexander Field in “A Great Leap Forward: 1930s Depression and U.S. Economic Growth,” was a macro-transformational change, “a revolution in factory organization and design in which traditional methods of distributing power internally via metal shafts and leather belts were replaced with electrical wires and small electric motors.” In other words, the electrification of manufacturing finally became a widespread and economically significant phenomenon.

So what modern advances might prove significant and widespread enough to cause a sustained productivity acceleration? Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning, is one top candidate. It’s why Stanford University economist and productivity-optimist Erik Brynjolfsson is betting — literally — on a New Roaring Twenties. Brynjolfsson: “Recent breakthroughs in machine learning will boost productivity in areas as diverse as biotech and medicine, energy technologies, retailing, finance, manufacturing and professional services.”

One example of AI’s becoming more diffused through the economy is this nugget in a new piece from Washington Post economics reporter Heather Long:

Some companies are also finding ways to harness machine learning. Even pre-pandemic, companies were automating scheduling and various administrative tasks. Now more sophisticated work is being done increasingly by machines. Last month, California software company Cadence Design Systems unveiled a new software they dubbed Cerebrus, a homage to the largest part of the human brain. It’s used to make microchip engineers more productive. On a recent call with Wall Street analysts, Cadence executives said Cerebrus makes chip engineers 10 times more productive, the kind of gain that could ultimately lower chip costs, not to mention getting faster turnaround for new products. “I believe Cerebrus is a fundamental breakthrough,” said Anirudh Devgan, president of Cadence Design Systems, on a recent earnings call.

AI is no longer just about replacing human customer service representatives with voice-recognition systems, she concludes. AI is more and more complementing workers and making them more productive. It’s also increasingly functioning as a sort of super research assistant. DeepMind, the UK-based artificial intelligence company owned by Alphabet, recently announced that its AlphaFold program can predict the structure of proteins, a stunning breakthrough that could dramatically accelerate drug discovery.

Now alongside this rapid AI advance and diffusion comes good news about nuclear fusion, a clean and potentially limitless energy source that has fueled the techno-optimist dreams of futurists for decades. But up until now, fusion has been little more than a tantalizing dream. “Nuclear fusion is the energy source of the future, and always will be,” if you want to be sarcastic about it. This tweet from roboticist Rodney Brooks also gives a sense of the long-term disappointment with fusion, framed as a comparison with autonomous vehicles:

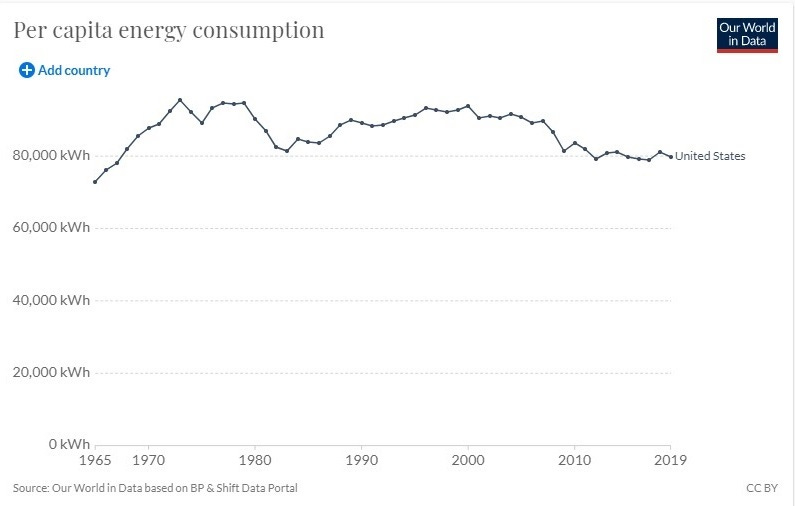

Indeed, some argue that a lack of energy innovation — including a retreat from nuclear fission — helps explain the sudden and surprising downshift in productivity growth that began in the early 1970s. Between the emerging anti-growth environmental movement and oil shocks, we started focusing on energy efficiency rather than abundance.

But the New York Times piece offers evidence that the technology’s century-old promise can be more than just a dream. From the NYT:

Researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory reported on Tuesday that by using 192 gigantic lasers to annihilate a pellet of hydrogen, they were able to ignite a burst of more than 10 quadrillion watts of fusion power — energy released when hydrogen atoms are fused into helium, the same process that occurs within stars. . . . But the burst — essentially a miniature hydrogen bomb — lasted only 100 trillionths of a second. Still, that spurred a burst of optimism for fusion scientists who have long hoped that fusion could someday provide a boundless, clean energy source for humanity. . . . More promisingly, the fusion reactions for the first time appeared to be self-sustaining, meaning that the torrent of particles flowing outward from the hot spot at the center of the pellet heated surrounding hydrogen atoms and caused them to fuse as well. “It demonstrates to the skeptic that there is nothing fundamentally wrong with the laser fusion concept,” [one long-time fusion critic] said. “It is time for the U.S. to move ahead with a major laser fusion energy program.”

And this wasn’t the first major bit of fusion news over the past 12 months. In September of last year, the NYT ran this piece, “Compact Nuclear Fusion Reactor Is ‘Very Likely to Work,’ Studies Suggest.” Now there are other energy options, including advanced fission and next-generation geothermal. But workable nuclear fusion would certainly signal the New Roaring Twenties could turn into a Roaring Twenty-First Century.

The Short Read

⌛ Environmental reviews continue to slow and hamper Americas ability to build

Congestion traffic pricing isn’t just a way to raise money. Because valuable roadways are free to use, underpricing leads to shortages during rush hours and other busy times. As one analysis puts it, “Pricing the roads correctly can reduce that overuse, ease congestion, and make traffic flow more freely.”

It’s not an uncommon policy proposal. The New York Times points out that New York City’s aging subway system “was supposed to receive hundreds of millions of dollars for upgrades this year” via a congestion pricing plan. Specifically, fees on drivers entering Manhattan, from 60th Street to the Battery. Now here’s the billion-dollar hitch:

Even if congestion pricing gets [incoming New York Gov. Kathy Hochul’s] backing, it could be two more years before it kicks off. Before the tolls can start, the M.T.A. must conduct a federally mandated environmental assessment of the congestion pricing plan, which will examine its potential impact on traffic, air quality and the economy of the city and surrounding region. The plan can proceed if federal officials determine it creates no significant negative environmental impact. The M.T.A. plans to announce this month that the environmental review is scheduled to take 16 months, M.T.A. officials said. . . . The result is that the public transit system will lose out on a projected billion dollars in revenue for every year that passes without a congestion plan, and there will be no relief from traffic or pollution.

And it’s not just federal environmental reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act that make it hard to build in America, leaving the economy stuck in regulatory traffic. There’s also a state-level version of this story. From a super interesting tweetstorm:

If you’re looking for a balanced and thorough explainer about the history, process, and impact of environmental reviews, please check this out this long-read Q&A I conducted last year with Leah Brooks, associate professor in the Trachtenberg School of Public Policy and Public Administration at George Washington University and co-author, along with Zachary Liscow, of the 2019 paper, “Infrastructure Costs.”

The Micro Reads

Solar panels in space could help power the UK by 2039, claims report - New Scientist

Waymo Is 99% of the Way to Self-Driving Cars. The Last 1% Is the Hardest - Bloomberg

Economic Growth Is More Important than You Think - Human Progress

Artificial Intelligence may diagnose dementia in a day - BBC

Beyond Apollo: Taking One Giant Leap - Lockheed Martin

Exploration and exploitation in US technological change - Vasco M. Carvalho, Mirko Draca and Nikolas Kuhlen, University if Warwick