🚀 Missions to Mars: A Quick Q&A with … space analyst Peter Hague

'That we are even seriously talking about colonization now is purely down to the fact that two of the wealthiest men in the world want to expend their money and efforts making it happen.'

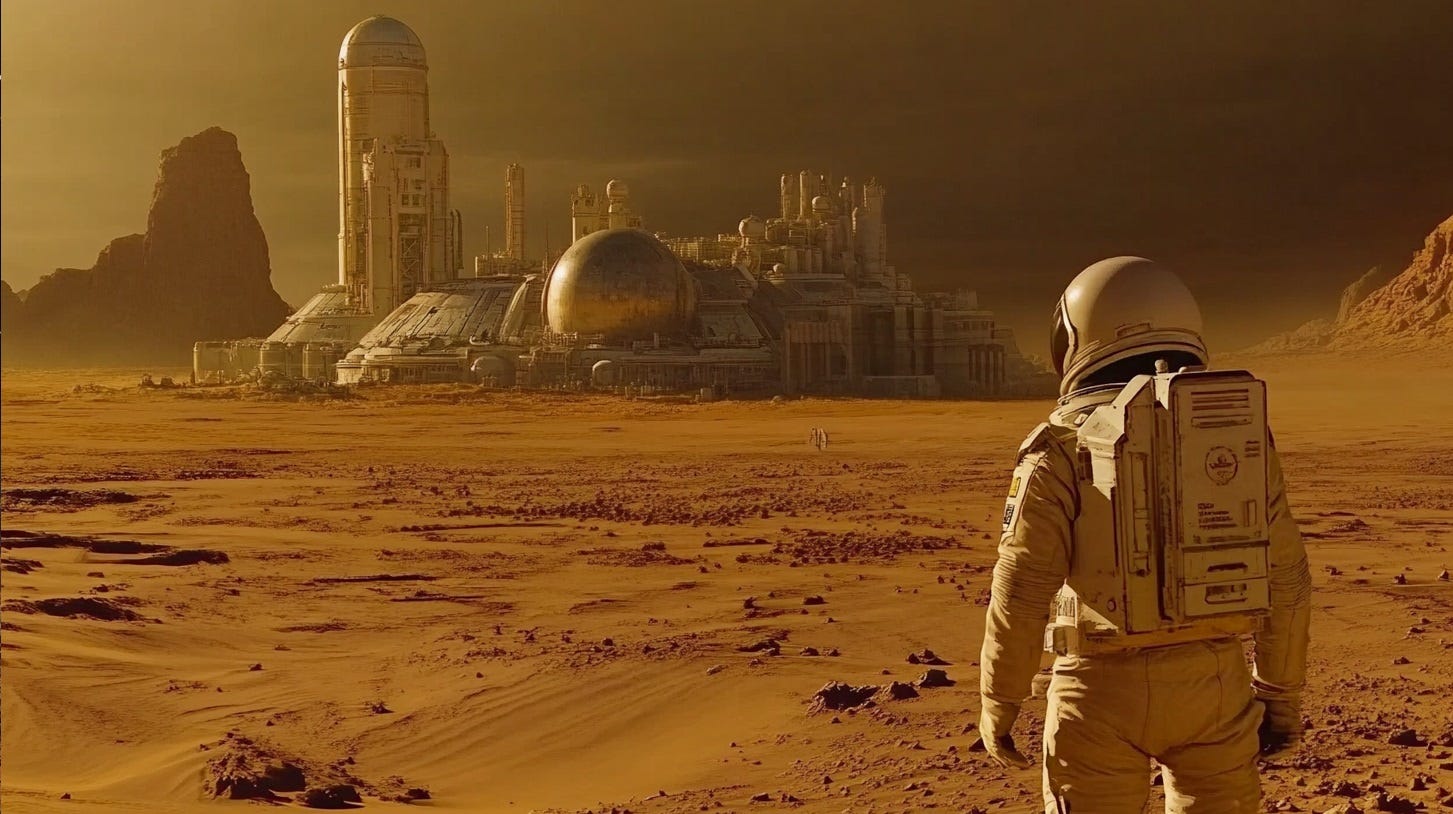

Putting a man on Mars seems less and less like a sci-fi plot and more like an inevitability — eventually. That, thanks to some of the world’s richest and most influential business moguls pinpointing Mars colonization as a personal priority. I asked Peter Hague a few quick questions about the motivations driving these moon-shot (and beyond) goals, the main hurdles standing in the way, and what competitive Mars colonization could look like in the (not-too-distant) future.

Hague is an astrophysicist and a scientific programmer at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology. He is the author of the Planetocracy Substack. His recent Quillette article, “Catching the Starship: A Breakthrough for Humanity” is worth a read.

1/ What should be the priority for initial Mars missions: scientific discovery, resource extraction, or establishing a self-sustaining human base?

The main priority for humans on Mars is building a base — it won't be self-sustaining for a long time, but we want to minimize the dependency on imports from Earth as much as possible, and get the most out of every kilogram we send out there. All other objectives on the surface, such as science or resource extraction, require some amount of material inputs (such as machinery) and the fewer of these you have to bring from Earth, the more of these objectives you can accomplish. The more self-sufficient a base is, the more people it can support, and human labour is still going to be an input for all our other objectives even with AI around to help.

2/ Can you explain what it means that the main barriers to interplanetary travel are primarily “mass problems” and how we’re best positioned to overcome them?

Problems in spaceflight and space colonization that are commonly raised as showstoppers which will require decades of research to work around are, in almost every case, problems that can be solved adequately by brute force scaling up of the amount of mass we send into space (or source from materials in space).

For example, astronauts in deep space are exposed to more highly penetrating galactic cosmic rays (GCR) than astronauts in Earth orbit are, and there are some concerns about the long-term impacts this will have on their health. But exposure can be reduced by either traveling through space faster, which requires more propellant and is thus a mass problem, or by adding heavy (meters thick) shielding which is not normally considered only because it would require a lot of mass. The need for higher reliability in machinery can be mitigated by sending more spare parts and redundant systems, using more mass.

The fact that we cannot yet build a completely closed-cycle life-support system — one where 100 percent of the consumables can be obtained from waste products — can be mitigated by sending enough consumables to make up the difference. Colonizing space is never going to be easy — but having more mass available makes almost every aspect of it easier, and there isn't really a point where you get diminishing returns from this process.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faster, Please! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.