Lost Future: What if America had avoided the Great Stagnation?

Also: the Biden infrastructure plan and the US economy; the neo-Space Age optimism of For All Mankind; a possible shift from the Great Stagnation to the Great Acceleration

“The past is the beginning of the beginning and all that is and has been is but the twilight of the dawn.” - H.G. Wells

In this Issue:

📉 Lost Future: What if America had avoided the Great Stagnation? (425 words)

🛣 What Biden’s overhaul of US infrastructure could mean for the US economy (425 words)

🚀 The neo-Space Age optimism of For All Mankind’s second season finale (621)

⏩ Why America might be ready for a long-run acceleration: a chat with AEI economist Michael Strain (718 words)

📉 Lost Future: What if America had avoided the Great Stagnation?

What’s been going on with American living standards over the past generation or so? “Stagnation” is the answer from populist politicians of the left and right, as well as from most of the serious media.

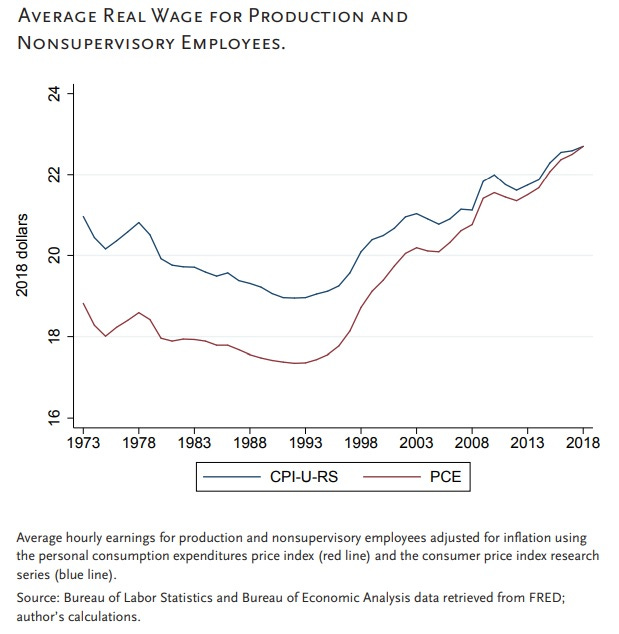

But I don’t think so. Although wages were stagnant or falling during the 1970s and 1980s, things eventually improved. Heading into the COVID-19 pandemic, notes AEI economist Michael Strain in his 2020 book, The American Dream is Not Dead, real wages for the typical worker had increased by a fifth since 1990 or (more likely) a third, depending on your preferred inflation measure. (See chart below from that book.)

To me, “stagnation” suggests zero progress or glacial progress — not the case over the past generation. This economic reality is important for politicians, pundits, and voters to understand amid the rise in “capitalism is broken” criticism.

Yet I’m also sympathetic to an alternate framing. How has America done vs. what was possible? What if the early 1970s Great Downshift in productivity growth — the most significant 20th century economic event other than the Great Depression — hadn’t happened? Economists Anna Stansbury and Lawrence Summers calculate that if productivity growth had been as fast over 1973-2016 as it was over 1949-1973 — twice as fast, basically — median compensation would have been around 41 percent higher in 2016, all else equal. Likewise, as the Bureau Labor Statistics recently noted, the downshift in productivity growth from the boomy mid-1990s to mid-2000s translates into a loss of $95,000 in output per worker (as well as an overall loss of $11 trillion in economic output).

Then again, the two above periods — the immediate postwar decades and the tech boom decade — might not have even been the periods that saw the most innovation and tech progress. As the Congressional Budget Office explained back in 2013:

After averaging somewhat more than 1 percent annually from 1900 to 1920, measured [total factor productivity growth] accelerated to nearly 2 percent on average during the 1920s and around 3 percent during the 1930s. Researchers attribute that big wave’ primarily to four clusters of critical innovations—electricity generation, internal-combustion engines, chemicals, and telecommunications—with nearly all of the important innovations in those clusters already in place well before World War II. [TFP is the part of growth explained by broad innovation and technological progress rather than inputs to production, such as number of hours worked or amount of capital deployed.]

Maybe the next big wave will be AI, robotics, advanced nuclear fission/fusion, and genetic engineering. America and the world needs a Big Upshift, and a big reason I’m doing this newsletter is to promote a policy environment where that’s more likely to happen. Faster, please!

🛣 What Biden’s overhaul of US infrastructure could mean for the US economy

One goal of President Biden’s agenda is to increase the economy’s long-run growth potential by improving the nation’s infrastructure. Making it easier for consumers and businesses to connect could boost productivity growth in numerous ways, such as lowering transportation costs, making inputs less expensive, and providing access to larger markets.

While there’s been criticism of Biden’s expansive definition of “infrastructure,” plenty in his more than $2 trillion plan meets the common definition: $115 billion to modernize bridges and roads, $85 billion to modernize public transit systems, $80 billion for rail, $100 billion for power infrastructure, $100 billion in proposed investment in broadband internet.

So some obvious questions, many of which are addressed in a super-interesting new Goldman Sachs report on the plan. For starters, is there even a big problem with US infrastructure? After all, it scores highly against that of other advanced economies (though not on internet bandwidth and electricity infrastructure).

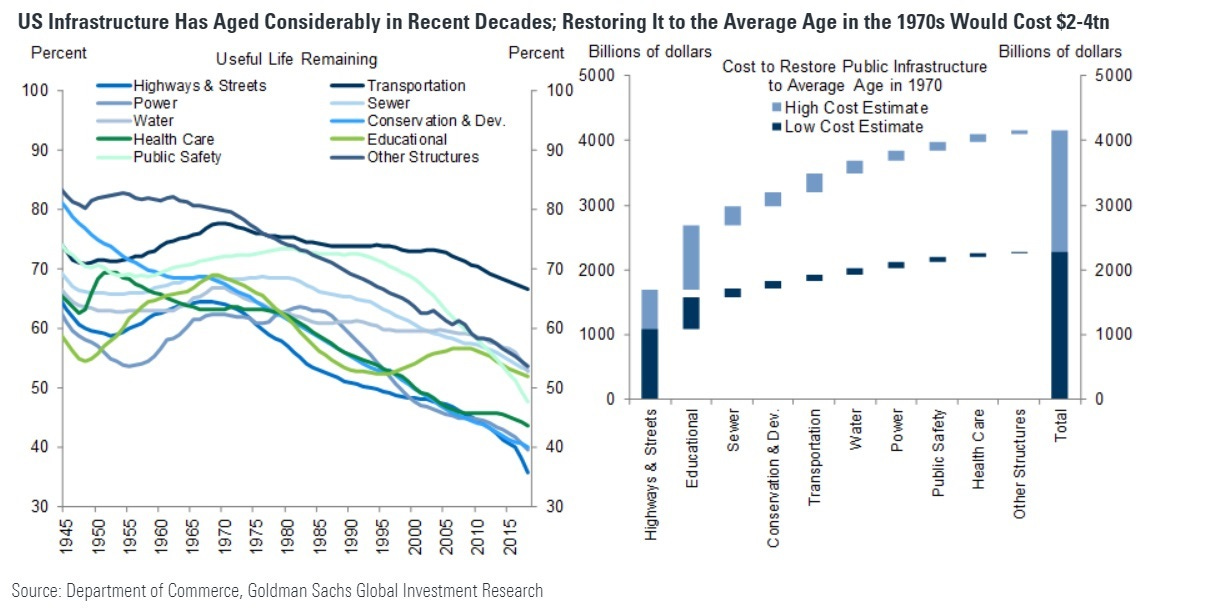

But GS notes that road congestion has gotten worse, and blackouts due to major disruptions have become more frequent. Much of core US infrastructure is more than a half-century old, raising maintenance and reliability issues. GS estimates it would cost $2 trillion to $4 trillion “to restore the average age of the public core infrastructure stock to its 1970 level, with highway restoration accounting for much of the cost.”

The difference in costs depends on whether new infrastructure replaces existing infrastructure at the end of its useful service life or if it replaces infrastructure whose age is average for the existing stock. A few GS charts help tell the story:

After reviewing the economic literature and applying those estimates to the Biden plan, GS estimates the proposal “would eventually raise the long-run level of potential output by a bit less than ½ percent. This does not account for any effects of ‘intangible infrastructure’ investments in research and development or any effects of proposed social benefits on potential labor supply, both of which are beyond the scope of our analysis.”

Not a small improvement, but let me make a few comments here. First, I again recommend regulatory reform to get more bang for the investment buck. Second, I worry that the business and investment tax hikes accompanying the plan will offset much of its growth impact. Third, I’m not sure either of the replacement goals suggested by GS are the correct or necessary ones. Seem arbitrary. Fourth, there is the opportunity cost of government spending so much on infrastructure (and eschewing private capital) versus other priorities such as even more science investment spending. Fifth, I would expect passage of most of this agenda.

🚀 The neo-Space Age optimism of For All Mankind’s second season finale

The inaugural issue of Faster, Please! featured a chat with TV writer and producer Ronald D. Moore. Best known for his 2004-2007 reimagination of Battlestar Galactica, Moore also wrote a ton of Star Trek: The Next Generation earlier in his career. For All Mankind, his latest show, just completed its second season on Apple TV+. Not only is For All Mankind a compelling alt-history drama — the Soviets beating America to the Moon is the path-changing event — but it’s a rare instance of Hollywood producing techno-optimist content. And the finale delivered on that upbeat theme.

If you’re not already watching or are a bit behind, here’s your Spoiler Alert. Anyway, while the finale deftly resolves myriad running stories, the key plot thread is a riff on the Cuban Missile Crisis — except this time it’s the Soviet Union running a quarantine of the Moon in 1983. Even with a lunar confrontation ready to spark to a nuclear conflagration back on Earth — sirens are sounding, and people are scurrying into civil defense shelters — a group of astronauts and cosmonauts defy orders and go through with the Apollo–Soyuz docking mission (something that happened in 1975 in our reality).

Meanwhile, President Reagan (elected instead of Jimmy Carter in 1976 by narrowly defeating President Ted Kennedy) is aboard Air Force where Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger is ominously telling him that they “may have to do something forceful.” Reagan agrees — but then he sees the televised images of the smiling space explorers from two nations shaking hands in orbit. He then telephones the head of NASA, a former astronaut herself: “This Apollo-Soyuz business … it was beautiful. And Nancy thought so, too. Four patriots of different nations coming together — well, it was just inspirational.” Reagan then reroutes Air Force One to Moscow where he and Soviet leader Yuri Andropov negotiate an end to the standoff.

(Moore gets that Reagan the Cold Warrior was also Reagan the Utopian, someone who in 1987 told the United Nations General Assembly, “I occasionally think how quickly our differences worldwide would vanish if we were facing an alien threat from outside this world. And yet, I ask you, is not an alien force already among us? What could be more alien to the universal aspirations of our peoples than war and the threat of war?”)

The show then flashes forward to 1995, and like something out of a Disneyland “Mission to Mars” exhibit, the camera pulls back as if the viewers themselves are launching into orbit, then hurtling past the colonized Moon and, finally, descending onto the Red Planet, where the episode concludes with a boot stepping onto Martian soil. (Here’s the timeline of the show, by the way.)

Befitting Moore’s background, there was a lot of Star Trek: The Original Series in the episode. ST: TOS was a Cold War-era television show that frequently explored the theme of societal conflict (A Taste of Armageddon, Errand of Mercy, The Omega Glory), often — though not always — providing a hopeful resolution in sync with creator Gene Roddenberry’s optimism.

I don’t know what the geopolitics of 1995 will be like in the universe of For All Mankind. I mean, 1995 on this world was pretty good. The Soviet Union was defunct, liberal democratic capitalism was expanding, and the Internet had arrived. That said, America had stopped striving to be a nuclear-powered, multiplanetary civilization as remains the case in For All Mankind. Something was lost along the way in our reality. I can’t wait to see what peace, prosperity, and greater civilizational aspiration bring in season three. Perhaps For All Mankind will fulfill the dream of Apollo-Soyuz astronaut Tom Stafford, who said back in 1975, “When we opened this hatch in space, we were opening, back on Earth a new era in the history of man.”

⏩ Why America might be ready for a long-run economic acceleration: a chat with AEI economist Michael Strain

I recently moderated an AEI panel that examined the Great Stagnation, the American economy’s productivity slowdown since the early 1970s — especially the period since 2005 after the 1990s tech boom finally waned. Here are some insights on the subject from Michael Strain (also mentioned above), AEI’s director of economic policy studies, who was on that panel:

Pethokoukis: Is the Great Stagnation permanent?

Strain: If you look at specific technologies, we’re getting much better at batteries, we’re getting much better at therapies like vaccines, we’re getting much better at artificial intelligence — you can go onto YouTube and find videos of driverless trucks going down the highway. These are very specific, concrete, tangible innovations and technologies that you can point to. And the question is, at some point, are businesses going to figure out how to make money using them? And I think the motivation there is so strong that the answer is surely “yes.”

We will see tech progress actually show up in the economic statistics?

If we can go into the lab and create a malaria vaccine in two weeks, that would be a game-changer for human welfare. I wouldn’t expect it to show up in US productivity statistics the year after or the year after that, but a world where we aren’t losing so much talent and skill to malaria will look a lot different than the status quo. And maybe 10 years from now, there’s a renaissance in Africa of invention — you know, there’s a Bill Gates figure who pops up who would have died of malaria but who didn’t, and then we can all benefit from that. And so my view is that over a suitably long time horizon, that malaria vaccine would show up in the US productivity statistics.

Are you worried about society, especially in this populist age, having less tolerance for the kinds of disruptions that economic growth and progress naturally cause?

We just defeated the plague in a year. That was technology, and that was the big, bad pharmaceutical companies that did that. And I think it’s still too early to say, but I wonder if there won’t be more warmth toward kind of abstract notions of creative destruction and abstract notions of the importance of innovation as a consequence of what I think is reasonably widely viewed as a pretty stunning technological success in terms of the vaccine.

Will AI or robots take all the jobs?

Advances in technology have been reshaping the labor market for decades, and we’ve seen new ways of producing manufactured goods, new ways of doing clerical work, and new ways of doing other really important economic activities completely change relative to what they looked like in the 1970s or 1980s. And we’ve seen huge changes in the distribution of employment across occupations. There’s much less employment in middle-skill, middle-wage occupations than there used to be, and that has had enormous consequences for our society, for politics, and for the economy. And I expect that kind of process is going to continue as businesses learn how to integrate newer technology. And that is very disruptive, even if it does not spell the end of human work.

If we look back a decade from and see the Great Stagnation continuing, what probably went wrong?

If the technologies that we see existing haven’t found ways of being used and aren’t showing up in productivity statistics, that seems to me to not really be an issue of public policy. My worry about policy is that it prevents the emergence of new technologies — that we’re not doing enough to support research and development, that we are unnecessarily holding back entrepreneurism and unnecessarily holding back business investment in a way that’s preventing new ways of doing things or new technologies from being invented.

What is pro-progress economic policy?

We need to let in way more high-skilled immigrants, we need to give a green card to any immigrant who graduates in the STEM field from a US research university, we need to have much more government funding of scientific research. We need to allow businesses to invest in research and development more than they currently do, we need to have a culture that encourages risk-taking and that encourages entrepreneurship.

Bill Nelson’s Flawed Vision for NASA - NRO | Tech policy analyst Will Rinehart doesn’t think the former senator — the second sitting member of Congress to travel into space, aboard Space Shuttle Columbia — has the right stuff to oversee the space agency: “The United States needs a clear vision for space, which NASA should manage. NASA, in turn, can best achieve this vision by budgeting wisely and working with commercial operators such as SpaceX and Blue Origin instead of wasting money building it itself.”

Who will win the self-driving race? Here are eight possibilities - Ars Technica | Waymo is the only company to have launched a fully driverless commercial taxi service. But they may not be the big winner, writes reporter Timothy Lee. Business model may be as important as execution. Or maybe this: “Another possibility is that nobody wins: maybe self-driving is an even harder problem than people appreciate, even after years of setbacks, and it will take decades, rather than years, to get working.”

17 Reasons to Let the Economic Optimism Begin - New York Times | Among those 17 reasons from economics correspondent Neil Irwin, here are a few of my favorites: (a) we’re entering the good part of the “productivity J-curve,” (b) cheap batteries and solar cells could be general-purpose energy innovations, and (c) economist and productivity-pessimist Robert Gordon seems a bit less pessimistic.

NEPA: Vehicle of Vetocracy? - Exponents | A good explainer of both NEPA and how the regulation could bog down Biden’s agenda, especially the clean energy and infrastructure plans: “The high-voltage transmission lines needed for the low-carbon, electricity-centered energy system the Biden administration has promised are particularly ripe for NEPA slowdowns. … Another NEPA-centric problem for the Biden plan is that, if we rule out reliance on a supply chain controlled from Beijing, it will necessitate a significant expansion of the mining and processing of rare earths and other minerals. The White House says it will use smart, coordinated infrastructure permitting to expedite federal decisions, but lacks an outline to dredge NEPA’s procedural morass. Under the existing review regime, the plan faces long odds.”

Higher than the Shoulders of Giants; Or, a Scientist’s History of Drugs - slimetimemold | This wild blog post keeps popping up in my Twitter timeline thanks to its novel (at least to me) theory: that the 1970 Controlled Substances Act played a role in the early 1970s Great Downshift in productivity growth by limiting access to imagination expanding drugs such as LSD:

Leaving out caffeine and alcohol was the only thing that spared us from total economic collapse. Small amounts of progress still trickle through; drugs continue to inspire humanity. … Steve Jobs famously took LSD in the early 70’s, just after the crackdown was revving up. … Bill Gates has been more coy about his relationship with acid, but when an interviewer for Playboy asked him, “ever take LSD?” he pretty much admitted it. … So it seems like LSD had a small role in the lead-up to both Apple and Microsoft. … The big scientific breakthrough made on LSD after the drugs shutdown of 1970 is perhaps the most important one of all, Kary Mullis’s invention of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in 1983. … Is the Controlled Substances Act really responsible for the general decline since 1970? We’re not sure, but what is clear is that drugs are foundational technologies, like the motor, combustion engine, semiconductor, or the concept of an experiment. New drugs lead to scientific revolutions. Some of those drugs, like coffee, continue to fuel fields like mathematics and computer science, even some hundreds of years later.