⤴ Let's add AP Progress to the high school curriculum

From the Industrial Revolution to the emerging AI Revolution, American students need to understand how economic growth and technological progress made the modern world

I’m not a planespotter who hangs around airports watching takeoffs and landings. And to be honest, I’ve flown less than a lot of people I know (though I should get some extra credit for zooming around China about a decade ago). So when I read on Tuesday that the final Boeing 747 was delivered to cargo carrier Atlas Air — there was even a ceremony at the aerospace company’s plant in Everett, Washington — I was a bit surprised. They were still manufacturing it? Indeed, Boeing was. Overall, 1,574 747s were built for more than 100 customers since the aircraft was first introduced at the Paris Air show in 1969 and first entered commercial service in 1970.

Now, had you asked Boeing executives back then about the future of the first widebody passenger jet, I doubt they would’ve predicted such quantity or longevity. Everyone knew the future of air travel was supersonic, especially Boeing. In 1966, the US federal government chose the company to build the prototype for the country's first supersonic transport, meeting a challenge posed by President John Kennedy on June 5, 1963, in a graduation speech at the US Air Force Academy. Unfortunately, design issues, rising energy costs, environmental opposition, and government budgetary concerns killed the SST. There might not be any more obvious sign of the Great Stagnation in technological progress than the stagnation in commercial flight speed.

That said, the 747 turned out to be a pretty good consolation prize. As The Economist wrote on its 50th anniversary:

To say that the 747 revolutionised air travel when it entered commercial service in 1970 is an understatement. Saying it opened the skies to the masses is closer to the mark. As the first passenger plane ever built with a twin-aisle cabin configuration, it was twice the size of its predecessor, the Boeing 707. That gave airlines the economies of scale they needed to sell cheap tickets on long-haul routes for the first time. Its roomier cabins, with less noise from jet engines, made long-haul travel much more comfortable too. The 747’s upper deck, that formed its distinctive hump, became the most coveted place in the sky. More than 1,500 of the planes have been delivered over the past five decades. Not many people, even the geekiest of aviation enthusiasts, can distinguish an Airbus A330 jet from a Boeing 777–two of the jumbo’s modern successors–when they soar overhead. But almost every traveller can recognise the 747’s hump.

So, yeah, a pretty important innovation. So important, however, as to be one of the key innovations of the 20th century? Not according to economist and journalist Tim Harford, host of the 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy radio show and podcast. And that’s OK. Look, I’m not saying the 747 is right up there with the internal combustion engine (#1) and the Haber-Bosch process (#2) — although one could make a strong case that it’s at least as important as the disposable razor (#17).

Still, thinking about where the 747 ranks among the great things of the Industrial and Information Revolutions got me thinking: How many of Harford’s selections does the average American high school student know much about, much less understand their importance to the modern world? Take the Haber-Bosch process, which enables us to mass produce synthetic ammonia fertilizer by combining hydrogen with nitrogen from the air using high heat and pressure. Without Haber-Bosch, the world’s population wouldn't have tripled over the 20th century. As the always excellent Human Progress site notes, “It is estimated that if average crop yields remained at their 1900 level, the crop harvest in the year 2000 would have required nearly four times more cultivated land than was actually cultivated. That equates to an area equal to almost half of all land on ice-free continents – rather than just the 15 percent that is needed today.”

You should probably leave high school knowing who Nobel laureate chemists Haber and Bosch were, as well as how the process works and its impact on humanity. Same goes for Norman Borlaug and his key role in the Green Revolution development of high-yielding crop varieties, especially rice and wheat, and more productive agronomic techniques. The three of them are world historic scientific figures.

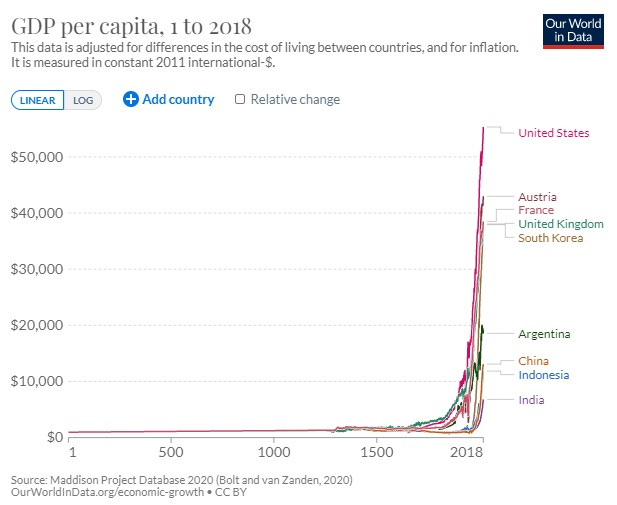

Here's where I’m going with this: The exponential advance in technological progress, economic growth and productivity, and human welfare over the past two centuries is the defining fact of the past quarter millennium. It would be worthwhile to directly teach high schoolers about the Great Acceleration and Enrichment — the who, what, where, when, why, and how of it. They should understand what’s going on with this chart:

There should be a class about it. Let’s call it Advanced Placement Progress. AP Progress would teach economic history through the lens of technological progress. One could imagine a course of study beginning with the Great Inventions of pre-industrial times, such as the compass and printing press, and then proceeding through the various stages of the Industrial Revolution: first (spinning jenny, steam engine, cotton gin, railroads, telegraph), second (internal combustion engine, telephone, lightbulb, automobile, aircraft), and third (semiconductors, mainframe computing, personal computing, and Internet). Of course, one might also want to include innovations that aren’t technical, such as the research lab and stock options.

Just imagine the unit on the rise of Silicon Valley. If the contents were anything like those found in The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America, the compelling history of the world’s tech hub from University of Washington historian Margaret O’Mara, AP Progress students would learn a 70-year story about the rise of Big Government, changing US economic policy, the Cold War, Project Apollo, the emergence of political conservatism, the impact of Moore’s Law, entrepreneurship, and antitrust, among many potential topics.

At a more basic level, I agree with Jason Crawford over at Roots of Progress that everyone should have a basic understanding of how an “industrial civilization” works, of the facts of history that too many of us don’t know. Everyone should know, for instance, that “half of everyone you know over the age of five is alive today only because of antibiotics, vaccines, and sanitizing chemicals in our water supply. That before these innovations, infant mortality (in the first year of life) was as high as 20%.” Maybe call that class Honors-level Progress. (By the way, Crawford has assembled an online program of guided self-study in the history of industrial civilization for high school students.)

Micro Reads

▶ The race of the AI labs heats up - The Economist |Neither AI was clearly superior. Google’s was slightly better at maths, answering five questions correctly, compared with three for ChatGPT. Their dating advice was uneven: fed some actual exchanges in a dating app each gave specific suggestions on one occasion, and generic platitudes such as “be open minded” and “communicate effectively” on another. ChatGPT, meanwhile, answered nine sat questions correctly compared with seven for its Google rival. It also appeared more responsive to our feedback and got a few questions right on a second try. Another test by Riley Goodside of Scale AT, an AI startup, suggests Anthropic’s chatbot, Claude, might perform better than Chatgpt at realistic-sounding conversation, though it performs worse at generating computer code. The reason that, at least so far, no model enjoys an unassailable advantage is that ai knowledge diffuses quickly. The researchers from all the competing labs “all hang out with each other”, says David Ha of Stability AI.

▶ Could ChatGPT do my job? - Melissa Heikkilä, MIT Tech Review | It’s not necessarily a bad thing if we can outsource some of the boring and repetitive parts of journalism to AI. In fact, it could free journalists up to do more creative and important work. One good example I’ve seen of this is using ChatGPT to repackage newswire text into the “smart brevity” format used by Axios. The chatbot seems to do a good enough job of it, and I can imagine that any journalist in charge of imposing that format will be happy to have time to do something more fun. That’s just one example of how newsrooms might successfully use AI. AI can also help journalists summarize long pieces of text, comb through data sets, or come up with ideas for headlines. In the process of writing this newsletter, I’ve used several AI tools myself, such as autocomplete in word processing and transcribing audio interviews.

▶ Roboticists want to give you a third arm - IEEE Spectrum | Such scenarios may seem like science fiction, but recent progress in robotics and neuroscience makes extra robotic limbs conceivable with today’s technology. Our research groups at Imperial College London and the University of Freiburg, in Germany, together with partners in the European project NIMA, are now working to figure out whether such augmentation can be realized in practice to extend human abilities. The main questions we’re tackling involve both neuroscience and neurotechnology: Is the human brain capable of controlling additional body parts as effectively as it controls biological parts? And if so, what neural signals can be used for this control?

Improving people's awareness is good but does it have to be relegated to an AP course? Could better education be done just through a TikTok series?

Yes!!! I wholeheartedly agree that teaching young people about progress in schools is a great goal to pursue. I see how my daughter is studying AP European History and how little of this gets covered--and I can imagine how much more engaging an AP Progress program would be, especially if it was delivered along the lines of Jason's course.