Jeff Bezos blasts off; climate and collapse; good news on productivity growth; and much more ...

“New and improving technologies aided by today's fortuitous discoveries [will] further man's potential for solving current perceived problems and for creating an affluent and exciting world. Man is now entering the most creative and expansive period of history. These trends will soon allow mankind to become the master of the Solar System.” - Herman Kahn, 1976

In this Issue:

🚀 Yes, It’s OK to be happy about the billionaire Space Race

🌡 The risk of planetary collapse from climate change

📈 How the Great Pandemic is boosting productivity growth

🎬 To boldly go where no one has gone before: Is optimistic sci-fi possible?

🚀Yes, It’s OK to be happy about the billionaire Space Race

Another billionaire will be blasting off to (suborbital) space tomorrow. Blue Origin is scheduled to launch its first crewed mission — one including company founder Jeff Bezos, his brother Mark Bezos, one of the Mercury 13 and aviation pioneer Wally Funk, and 18-year-old Oliver Daemon. And given our populist age, some folks are unhappy about the “billionaire space race.” Here are a few comments from critics of the recent flight (on a rocket plane) by Virgin Galactic’s Richard Branson:

“Our social, political, and economic systems are built around the idea that tax breaks for billionaires buying leisurely space travel is more important than feeding, clothing, and housing all our children.” - Rep. Jamaal Bowman (D-NY)

“Here on Earth, in the richest country on the planet, half our people live paycheck to paycheck, people are struggling to feed themselves, struggling to see a doctor — but hey, the richest guys in the world are off in outer space! Yes. It's time to tax the billionaires.” - Senator Bernie Sanders

“Billionaires jetting into space for fossil-fuelled [sic] joyrides while the planet literally burns is really not a good look.” - Degrowther Jason Hickel

“The space race playing out among billionaires like Richard Branson, Jeff Bezos, and Elon Musk has little to do with science — it’s a PR-driven spectacle designed to distract us from the disasters capitalism is causing here on Earth. . . . We desperately need the public to see through the spectacle of the billionaire space race and recognize that they’re not laying the groundwork for a fantastic future, or even advancing scientific knowledge about the universe. They’re trying to extend our ailing capitalist system, while diverting resources and attention from the most pressing challenge the overwhelming majority of the planet faces. Instead of letting the billionaires keep playing in space, we need to seize the wealth they’ve extracted from us and redeploy it to address the climate crisis — before it’s too late.” - Jacobin Magazine writer Paris Marx

These comments reflect a “rockets versus butter” argument as old as the original US-USSR Space Race. It’s bitterly captured in Whitey on the Moon, a 1970 spoken word poem by Gil Scott-Heron that’s featured in the 2018 biographical film about Neil Armstrong, First Man. The poem begins: A rat done bit my sister Nell (with Whitey on the Moon)/Her face and arms began to swell (and Whitey's on the Moon).

And as I write in my new The Week column, this skeptical view of space adventuring can be found in Summer of Soul, a new documentary about the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival in New York City. The Apollo 11 moon landing happened during the concert series. But attendees were less than impressed. One young Black man put it this way. “The cash they wasted, as far as I’m concerned, in getting to the Moon could have been used to feed poor Black people in Harlem and all over the place, all over this country. So like, you know, never mind the Moon. Let’s get some of that cash in Harlem.”

Of course, there wasn’t really a trade-off. America in the 1960s was choosing butter, guns, and rockets. At the same time that Americans were journeying further into space, Washington was launching a War on Poverty, creating such programs as Food Stamps, Medicaid, and Medicare.

This time around, critics are attacking private space efforts as indicating those billionaires just have too much money to spend, especially on frivolities such as space tourism for themselves and other super-rich folks.

But these warmed-over anti-space arguments are wrong. A few thoughts:

First, the hot-take economic argument on the left is that deficits don’t matter (much), and the US has a tremendous amount of fiscal runway left ahead of it. Believers in this theory can’t also say their priorities aren’t being funded because billionaires aren’t taxed enough.

Second, great tech advancements often start out looking like toys or playthings of the rich. That includes the now globally ubiquitous smartphone — as well as the very first telephone. These investments by the private sector may well result in a multi-trillion space economy, as I note in The Week. And those toys might also help protect Earth from unexpected space objects smashing into it.

Third, there’s also little double that recent space advances — especially the drop in launch costs thanks to Musk’s SpaceX — as well as smartphone tech miniaturization has been a big boost for space science. Here’s Sara Seager, a professor of planetary science and physics at MIT, in a podcast chat with me:

Pethokoukis: Sara, are you generally comfortable with the privatization of space, space launches, and the perhaps changing mission for NASA?

Seager: Absolutely. Even more than comfortable, just thrilled. Private companies’ involvements are actually bringing down the cost to go to space. While they have to do that for their own sustainable business, everyone benefits from that lowering of costs.

I always smile when I remember an MIT-led NASA mission called TESS that I just stepped down from a leadership position on. TESS is a planet-hunting telescope that finds about 50 new planet candidates every month — that’s like 50 new worlds a month out there. And TESS was launched on the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, which was much larger than what was actually needed for the mission — it was like having a giant suitcase inside a school bus. And we had so much extra space, because the Falcon 9 rocket was still cheaper than whatever else was available, even if it was smaller. That’s just one example of how private companies are bringing costs down.

This idea of sending a small rocket to Venus or Mars will change the scope of how space science operates. Right now, we spend billions of dollars on missions but don’t go very often, nor do we go with something that everyone has a part of. However, if we can send small, focused missions more frequently, it will change the game.

Fourth, there’s the JFK “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard” sort of reasoning. There is something spiritual as well as materialist about space. As Charles T. Rubin wrote recently in the New Atlantis:

I came to see human space exploration as a chance to maintain the expression of some human traits that would come to be in short supply in a world increasingly characterized by the drive for efficiency and comfortable self-preservation — traits like ingenuity, risk-taking, cooperation, and courage as they are to be found not in markets or war, but in exploration and pioneering. These enterprises are pretty well baked into what it means to be human and yet in danger of being lost in an increasingly settled and known world. . . . We should want heroes, but heroism requires danger. That many professed shock when the idea was floated that early Mars explorers might have to accept that they would die on Mars is a sign of how far we miss the real value of our space enterprise as falling within the realm of the “noble and beautiful.” It would be better to return in triumph, to age and pass away gracefully surrounded by loved ones, and admired by a respectful public! But to die on Mars — to say on Mars what Titus Oates said in the wastes of Antarctica, “I am just going outside and may be some time” — would be in its own way a noble end, a death worth commemorating beyond the private griefs that all of us will experience and cause.

🌡The risk of planetary collapse from climate change

Climate scientists are pushing for the development of shared supercomputer to more accurately project the potential severity of extreme weather. That’s according to the BBC, which also notes “top climate scientists have admitted they failed to predict the intensity of the German floods and the North American heat dome.”

Such forecasting failures really get to the heart of my concern about climate change. Whenever policymakers attempt to do a cost-benefit analysis of possible policy actions — and it is totally appropriate for such an analysis to be done, whether the policy is a tax, a regulation, or an investment — extreme tail risks need to be identified, noted and even overweighted in calculations. And one reason I suggest an “overweighting” is the dodgy track record we humans have with understanding and acting on risk in complex systems full of interdependencies, feedback loops, and nonlinear responses. (And, according to those aforementioned climatologists, their computer models are similarly flawed.)

This was also the view of the late Harvard University economist Martin Weitzman, who cautionary advice about climate forecasting deserves remembering and repeating today. From is 2009 paper “Some Basic Economics of Extreme Climate Change”:

Climate change is characterized by deep structural uncertainty in the science coupled with an economic inability to evaluate meaningfully the welfare losses from high temperature changes. The probability of a disastrous collapse of planetary welfare from too much CO2 is non-negligible, even if this low probability is not objectively knowable.

And from a separate paper on the economics of climate change:

I believe that the most striking feature of the economics of climate change is that its extreme downside is nonnegligible. Deep structural uncertainty about the unknown unknowns of what might go very wrong is coupled with essentially unlimited downside liability on possible planetary damages. This is a recipe for producing what are called ‘fat tails’ in the extremes of critical probability distributions.”

Those worrisome “fat tails” are why Weitzman favored research into climate engineering options in case some of the worst-case scenarios required “knocking down catastrophic temperatures rapidly.” He certainly wasn’t blasé about such radical “break the glass” options. Like any good economist, he assumed there would be unintended consequences. And he specifically worried about irresponsible “middle powers” acting recklessly and unilaterally, thus the need for international frameworks. But he took those potentially existential “unknown unknowns” seriously enough to leave everything on the table. And so should we.

📈How the Great Pandemic is boosting productivity growth

If this decade is going to be another Roaring Twenties — referring to the boomy 1920s that also followed a global pandemic — then we’re going to need to see faster productivity growth. And while that could be caused by radical new technologies or the spread and improvement of current tech, such as machine learning, the pandemic itself might prompt long-lasting business efficiencies that boost productivity growth, at least for a bit.

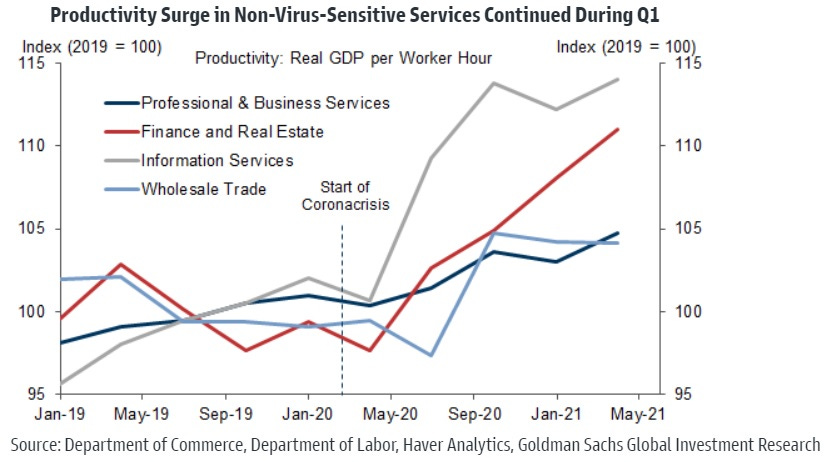

And this is just the scenario being put forward by megabank Goldman Sachs in a new research note. In “A Persistent Productivity Pickup,” the GS econ team look for proof to support its thesis we that pandemic-pushed workplace digitization “would boost efficiency in industries for which virtual meetings are feasible and in-person expenses like travel and entertainment could sustainably decline. . . . If this hypothesis is correct, the composition of coronacrisis productivity gains should be skewed towards these industries as well.” (Also ecommerce.)

And that “skew” is indeed what GS finds in the productivity data, and the skew seems to be continuing:

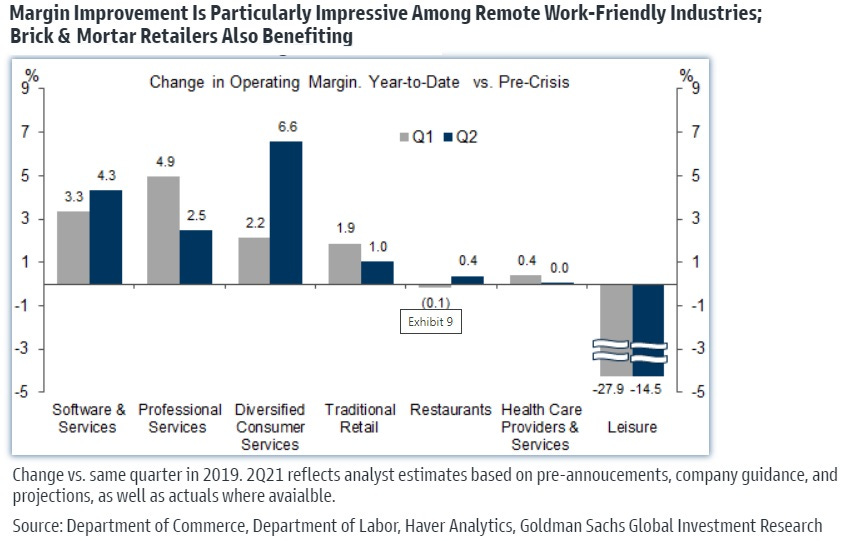

Moreover, GS finds that earnings margin improvement “has been especially pronounced in the same set of industries where gains from digitization are most clear-cut: information technology services, professional services, and non-virus sensitive consumer services.”

The GS conclusion: “Taken together, the GDP by industry and corporate earnings data are consistent with a pickup in the productivity trend from 1½% pre-pandemic to around 3% over 2020-2022.”

Hopefully, other factors will promote a longer-run productivity acceleration, one that spans the decade. Economist Erik Brynjolfsson is actually betting productivity-pessimist Robert Gordon that such an upturn will happen, a forecast based in part on the prediction that recent breakthrough in AI, particularly machine learning, will accelerate scientific discovery and “boost productivity in areas as diverse as biotech and medicine, energy technologies, retailing, finance, manufacturing and professional services” as it diffuses throughout the economy.

🎬 To boldly go where no one has gone before: Is optimistic sci-fi possible?

In this Substack, as well as in my Political Economy podcast and AEIdeas blog, I’ve lamented the lack of optimistic and techno-solutionist fiction. The long-term popularity of Star Trek, in all its incarnations, is the exception that suggests the rule — at least for the past half century.

Just check out the popular TV Tropes site. It’s an encyclopedic compilation of storytelling clichés, including several categories related to television programs — as well as films, books, comics, and video games — about life in a fictional future. Among them: Dystopia, Techno Dystopia, Dystopia Justifies the Means, Dark World, Future is Shocking, Future Scares Me, Ominous Message from the Future, False Utopia, and Zombie Apocalypse. That gives a pretty good sense of where modern sci-fi is. As William Gibson told the New York Times in 2020, “In my childhood, the 21st century was constantly referenced. You’d see it once every day, and it often had an exclamation point. We don’t seem to have, culturally, a sense of futurism that way anymore. It sort of evaporated.”

Occasionally, I’ll get push back on this view, often something like: “You can’t write interesting utopian sci-fi. That would be boring. If nothing is going wrong, there’s no tension, no story.”

But that misses my point. I'm not talking about sci-fi that imagines a perfect future, just an interesting future that one might want to live in. Some of today’s big problems solved, but new ones probably emerging. It’s a future occupied by recognizable flawed humans doing their best in an imperfect universe. Yet directionally more humane in many ways. Star Trek hardly depicts a utopia.

Take the ongoing series The Expanse on Amazon Prime Video. The show is set in the year 2350 when the average lifespan on Earth is 123 years, Mars has 3 billion inhabitants, and humanity mines deep space asteroids. Not dystopia, but not a utopia, given the brewing geopolitical conflict between Earth, Mars, and those mining colonies. Also, no zombies, incinerated Earth, or collapsed civilization. Humanity has survived and expanded. (I’m still in Season One, so I hope society does not collapse in subsequent seasons.)

I would also point to Working Futures from late 2019. It’s an anthology of 14 speculative stories about the intersection of jobs and advancing automation. In the book’s introduction, editor Michael Masnick writes that each story “contributes something to our thinking on the future of innovation and work, and what the world might soon look like — in both good and bad ways.”

Technology might help create a better society in some ways, but not a perfect one. Of course, it does. It solves problems, but also creates new ones, which the next advance solves. Rinse and repeat. Yet the overall direction is forward. As economic historian Joel Mokyr has written: “Whenever a technological solution is found for some human need, it creates a new problem. As Edward Tenner put it, technology ‘bites back’. The new technique then needs a further ‘technological fix’, but that one, in turn, creates another problem, and so on. The notion that invention definitely ‘solves’ a human need, allowing us to move to pick the next piece of fruit on the tree is simply misleading.” And so it goes.

Robotaxis: have Google and Amazon backed the wrong technology? - FT | “So if the evolutionary approach to building driverless technology proves successful, the upshot would be startling: the world’s biggest, most sophisticated companies — Alphabet, Apple, Amazon and Microsoft — would have all backed the wrong horse for a future technology widely expected to earn revenues in the trillions of dollars.”

WHO Panel Issues Gene-Editing Standards Aimed at Averting DNA Dystopia - WSJ

Start-Ups Aim Beyond Earth - New York Times

Why I’m a proud solutionist - Jason Crawford, MIT Tech Review

NASA Announces Nuclear Thermal Propulsion Reactor Concept Awards - NASA | “NASA is leading an effort, working with the Department of Energy to advance space nuclear technologies. The government team has selected three reactor design concept proposals for a nuclear thermal propulsion system. The reactor is a critical component of a nuclear thermal engine, which would utilize high-assay low-enriched uranium fuel. The contracts, to be awarded through the DOE’s Idaho National Laboratory (INL), are each valued at approximately $5 million. They fund the development of various design strategies for the specified performance requirements that could aid in deep space exploration.”

How to prepare for the AI productivity boom - MIT

Immigration, Innovation and Growth - NBER Working Paper | While the politics of immigration in 2021 America are no doubt dicey, it’s worth repeating what a tremendous asset it is that so many people want to come here. The return on good immigration policy is pretty amazing. And it’s documented in research paper after research paper. Here’s another one: “Immigration, Innovation, and Growth” by Konrad B. Burchardi (Stockholm University), Thomas Chaney (Science Po), Tarek Alexander Hassan (Boston University), Lisa Tarquinio (Boston University), and Stephen J. Terry (Boston University). Three key findings:

First, we show that, on average, immigration to the US between 1975 and 2010 had a positive causal effect on local innovation, local economic dynamism, and average wages of natives, where, for example, a 1% increase in immigration to a given county on average increased the number of patents filed by local residents by 1.7% over a five-year period. . . . Second, we find positive spillovers of these positive local effects, where, for example, an increase in a given US county’s immigration significantly increases the patenting rate in surrounding areas up to a distance of 250km (150 miles). Third, we find the effect of immigration on innovation and local wages is far from uniform. Instead, we show the arrival of highly educated migrants has a much larger positive effect on local innovation and wages than the arrival of migrants with little or no education.