🏭 Is the CHIPS Act really working?

Cutting checks is the easy part, but there's some reason for optimism

Quote of the Issue

“People are very open-minded about new things—as long as they’re exactly like the old ones.” - Charles Kettering

The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised

“With groundbreaking ideas and sharp analysis, Pethokoukis provides a detailed roadmap to a fantastic future filled with incredible progress and prosperity that is both optimistic and realistic.”

The Essay

🏭 Is the CHIPS Act really working?

Super-short Summary: The $280 billion CHIPS Act aims to boost US semiconductor manufacturing and reduce reliance on TSMC in Taiwan, which produces 92% of leading-edge chips, raising national security concerns. Historical analysis shows mixed results for US industrial policy, with R&D support being the most successful. The CHIPS Act's specific industry focus and national security objectives may justify federal intervention, despite early challenges in implementation. Success will be measured by whether the US increases domestic production of advanced chips to 20 percent by 2030, as targeted by the Biden administration, rather than by other metrics like job creation or the location of chip facilities.

Two ideas, which may or may not be in conflict: First, I agree with US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, who said at a House hearing on Wednesday that a Chinese invasion of Taiwan and seizure of chips producer TSMC would be an "absolutely devastating" economic event: "Right now, the United States buys 92 percent of its leading edge chips from TSMC in Taiwan.” Scary stuff.

Second, my first-order assumption is that industrial policy exemplifies the Hayekian fatal conceit of central planning. Government bureaucrats don’t possess the knowledge to effectively allocate resources and pick winners and losers — a task for which the market's decentralized price system is far better suited. (The Commerce Department + ChatGPT isn’t going to do the trick, sorry.)

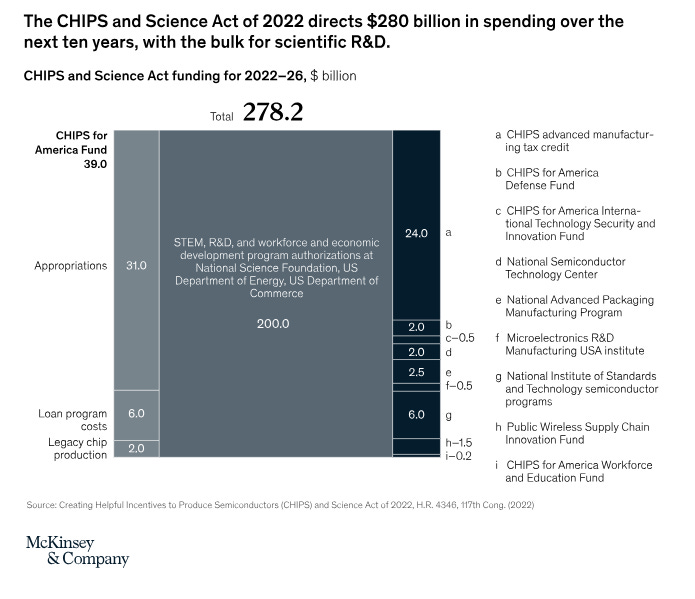

Given those beliefs, then, what do I make of Washington’s foray into the semiconductor industry through the $280 billion CHIPS and Science Act of 2022? The chip part includes nearly $40 billion in subsidies and grants to encourage domestic semiconductor manufacturing (with a focus on cutting-edge facilities), as well as investments in semiconductor R&D, and investment tax credit for investments in semiconductor manufacturing equipment and facilities.

Where things stand right now

Still early days, but my AEI colleague Chris Miller, author Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, likes what he sees, as he recently wrote in a Financial Times op-ed, “The Chips Act has been surprisingly successful so far.” Miller:

Samsung, TSMC, and Intel — the world’s leading chipmakers — are now building major new plants in the US. Intel will manufacture its most advanced chips there, while TSMC will introduce its cutting-edge 2-nanometre process in Arizona around two years after bringing it online in Taiwan. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo notes that by 2030, the US will probably produce around 20 percent of the world’s most advanced chips, up from zero today.

Of course, what we’ve seen so far is the aspect of industrial policy that’s easiest to pull off. It’s something familiar to many American CEOs and US state governors. “The global locational battle for fabs resembles, on a world scale, the battle between US states for automotive plants and other industrial prizes,” writes Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Megan Hogan in a 2022 Peterson Institute for International Economics policy brief on the CHIPS Act

Yet even that part isn’t so easy. The construction of the TSMC plant in Arizona has brought to light a significant culture clash between the work practices and management styles of TSMC’s home culture in Taiwan and the expectations of the American workforce. The Washington Post reports that “the companies have struggled to hire enough construction workers, especially welders and pipe fitters.” There’s also no guarantee that government checks will offset a series of poor past strategic decisions by Intel — including reluctance to invest in the most advanced manufacturing technologies — and enable it to again be a global leader in making cutting-edge chips. At least TSMC has shown it can produce cutting-edge chips, albeit in some other place.

My point: It’s still a long way from breaking dirt to churning out chips, even for companies already successful at doing so. The good news here is that we have a metric by which to judge this effort, courtesy of Raimondo: “I want to emphasize this point. We anticipate that America will produce 20% of the world’s leading-edge logic chips by the end of the decade, meaning our manufacturing capacity and supply chains will no longer be as vulnerable to geopolitical challenges as they are today.”

Productive capacity, then. Not jobs. Not “good jobs.” Not “good jobs in swing states.” Not share of jobs with nearby access to high-quality childcare.