Is slow population growth the ultimate obstacle to tech progress?

“Man is diminished if he lives without knowledge of his past; without hope of a future he becomes a beast.” - P.D. James, The Children of Men

The Long Read

🛑 Is population growth the ultimate obstacle to technological progress? (812 words)

“The Past and Future of Economic Growth: A Semi-Endogenous Perspective,” a marvelous new NBER working paper from Stanford University economist Charles I. Jones, ends with a helluva kicker: “I hope this essay convinces you that there are many exciting opportunities for future research on economic growth. This force has lifted billions of people out of poverty. It holds the promise of equally great advances in the future.” Love it, love it, love it.

But to understand the promise of economic growth, one must understand both what drives growth today and the forces that could either accelerate or decelerate growth in the future. Let’s start with a mystery that derives from this fun fact presented by Jones: “For the past 150 years, GDP per person in the United States has increased exponentially at a relatively stable rate of around 2 percent per year.”

Now to understand why that fact might seem mysterious to some economists, you have to understand the notion that economic growth comes from ideas. As Nobel laureate economist Paul Romer pointed out, ideas are nonrival. Once invented — whether the AlphaFold software code, the formula for mRNA vaccines, or techniques to create high-yield wheat — an idea can be used infinitely. So where do ideas come from? Well, you and me. . . and folks like CRISPR pioneer Jennifer Doudna and the Google guys, Sergey Brin and Larry Page.

So here’s the basics of Romer’s “semi-endogenous growth theory,” as explained by Jones: “People produce ideas and, because of nonrivalry, those ideas raise everyone’s income. This means that income per person depends on the number of researchers. But then the growth rate of income per person depends on the growth rate of researchers, which is in turn ultimately equal to the growth rate of the population.”

So like Soylent Green, economic growth is made from people. Which brings us to our mystery: If long-run economic growth comes from long-run population growth, how come US economic growth has far exceeded population growth? Indeed, Jones calculates that population growth contributed only around 20 percent of US economic growth since 1950. So where did the other 80 percent come from?

Jones offers a three-part answer: That other 80 percent is explained by rising educational attainment, increases in the fraction of the population devoted to R&D, and declines in misallocation (the unproductive distribution of capital and labor.)

So based on that model, why might economic growth be slower in the future than in the past? Jones:

Many of the sources of growth historically — including rising educational attainment, rising research intensity, and declining misallocation — are inherently limited and cannot go on forever. . . . [For example]: we cannot spend more than 100 percent of our time in school. . . . The key source of sustainable growth in the semi-endogenous setting is population growth. But that has been slowing historically around the world and current fertility patterns are more consistent with a declining population than with positive population growth. In the extreme, this could even lead to the stagnation of living standards for a vanishing population.

But there are also reasons why economic growth might be faster in the future, especially with better public policy. First, we could find more Einsteins. Jones notes that only maybe a couple of every thousand people in the world is engaged in research, and thus “we are a long way from hitting any constraint that we have run out of people to hunt for new ideas.” More economic development in China and India will expand the potential pool of new inventors. Jones: “How many Thomas Edisons and Jennifer Doudnas have we missed out on among these billions of people because they lacked education and opportunity?” Even in the US, fewer than 12 percent of inventors are women.

Second, artificial intelligence allows us to more thoroughly automate idea production. AI becomes an ever-improving research assistant. We’ve already seen this play out with AlphaFold and the the new antibiotic, Halicin. How far can this go? Jones speculates:

An extreme version of this model would involve artificial general intelligence (AGI): consider what would happen if machines could replace humans in all tasks. On the one hand, this scenario seems quite far-fetched. On the other hand, according to Davidson, many experts in the field of artificial intelligence believe there is a nontrivial chance of this occurring in the next century. If we replace all labor with capital in the task model — in both goods production and in idea production — then there are increasing returns to factors that can be accumulated because of the nonrivalry of ideas. Growth explodes, and simple math reveals a singularity in which knowledge and incomes go to infinity in finite time. . . . [Or perhaps] machines invent all possible ideas, leading to a maximum productivity, and then they fill the universe rearranging matter and energy to exponentially expand the “size” of the artificial intelligence.

The Short Reads

🌉 A counter-counter take on the Biden infrastructure plan | One criticism of the $1.2 trillion Biden infrastructure plan, approved by the Senate on Tuesday, is that it’s not ambitious enough. Mike Solana of the Founders Fund, for instance, titles his take “Trillion Dollar Paint Job.” The core of his critique: “We are not researching, designing, and building. We are repairing, and refurbishing. This entire bill is proudly ‘green.’ Old schools will be green, old housing projects will be green, old ports will be green! But they’ll still be old.” In a recent tweet, Solana give a sense of his vision:

I feel you, Mike! And if this bill is a one-off for the next decade or more — and it might be — my disappointment will be profound. That said, one problem with US infrastructure is that politicians would rather build a new road than fix the potholes in an existing road or upgrade century-old water pipes. There is a definite and documented maintenance gap. I would refer readers to my June podcast chat with AEI scholar Rick Geddes. When I asked how a rich country like the US allowed its infrastructure to erode so badly, he replied. “I think the answer is the way infrastructure has been procured or delivered by the state and local governments that own the infrastructure has caused them to focus more on the design and construction of new facilities and not the operation or maintenance of existing facilities over a longer period of time.”

Of course, you can repair and upgrade at the same time. That could mean the incorporation of new technologies into the operation of roadway maintenance such as sensors, new types of concrete, new types of line paint, smart stoplights, and smart street lights. State and local governments have been slow to adopt these improvements, which is why Geddes favors long-term contracts with private partners who are more likely to innovate. Now onto the megaprojects!

📈 Are economist starting to buy into the “New Roaring Twenties” thesis? | The worst reason to think we are experiencing an emerging productivity boom is because we’re experiencing a productivity boomlet. Over the past year, productivity growth has put in its best showing in over a decade. As JPMorgan explains: “This pickup likely reflects both shifts in the composition of economic activity away from low productivity industries as well as fundamental productivity acceleration brought on by the pandemic.”

It remains to be seen just how significant the pro-productivity changes nudged by the pandemic — such as work-from-home and more e-commerce — really are. Then there’s the stuff which really gets pro-progress folks excited, such as advances in machine learning algorithms, biomedical sciences, and energy. Economists Erik Brynjolfsson and Georgios Petropoulos: “. . . the bounty of technological advances, the compressed restructuring timetable due to covid-19, and an economy finally running at full capacity—the ingredients are in place for a productivity boom. This will not only boost living standards directly, but also frees up resources for a more ambitious policy agenda.”

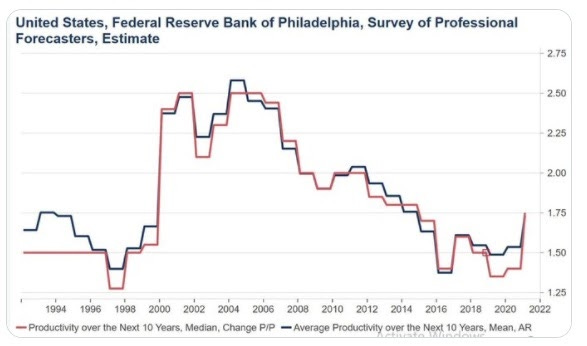

And this chart of productivity forecasts, courtesy of economist David Beckworth, suggests growing acceptance of Brynjolfsson’s growthy thesis:

🔬 Science policy isn’t just more money for science | The return from public science investment might be so large that it could reasonably be called an “extraordinary machine to benefit human progress,” as Northwestern University economist Benjamin F. Jones does in his recent paper. “Science and Innovation: The Under-Fueled Engine of Prosperity.” The $25 billion investment in Operation Warp Speed during the Covid-19 pandemic easily paid for itself many times over through accelerated vaccine development. Or this: Without the basic science of Albert Einstein, no GPS and no Uber.

Given that return, why is the US only now thinking about ramping up science investment, especially given the long-term productivity downshift? Jones: “An observation about U.S. science and innovation policy is that policymakers appear to go big (or, at least, go bigger) when perceiving specific threats.” So thanks, China, I guess.

But what should Washington do besides ramp up funding and bring in more immigrants? Jones argues that we need as much innovation in research institutions as research itself in “order to further explore the roads not traveled amidst the vast unknown.” Both the Office of Scientific Research and Development during World War II and Operation Warp Speed provide examples to consider. (I would also point to Focused Research Organizations as another intriguing possibility.)

📉 Bad economic policy, Maoism edition | China’s national rate of extreme poverty has fallen from nearly 90 percent in 1981 to under 4 percent today. That massive reduction is largely credited to the pro-market economic reform initiated in 1978 by Deng Xiaoping. The country abandoned policies based on Soviet-style central planning.

But what if China had abandoned the Maoist path earlier and copied the sort of economic policies implemented in the 1950s and 1960s in Taiwan and South Korea? That’s the counterfactual explored in the January 2021 working paper “Poverty in China since 1950: A Counterfactual Perspective” by Georgetown University economist Martin Ravallion.

Now the “political capitalism” pursued by those nations was hardly something Milton Friedman would have recommended. But farms were not collectivized nor were market incentives eliminated in those nations. Ravillion concludes: “When judged against the development paths of South Korea and Taiwan, this paper’s calculations suggest that the Maoist path meant that an extra quarter or more of the Chinese population were living in poverty by the time Deng’s reforms began.”

The Micro Reads

Geothermal energy is poised for a big breakout - David Roberts, Vox | “After many years of failure to launch, new companies and technologies have brought geothermal out of its doldrums, to the point that it may finally be ready to scale up and become a major player in clean energy. In fact, if its more enthusiastic backers are correct, geothermal may hold the key to making 100 percent clean electricity available to everyone in the world. And as a bonus, it’s an opportunity for the struggling oil and gas industry to put its capital and skills to work on something that won’t degrade the planet.”

A Negative Delta in Asia - Jan Hatzius, Goldman Sachs | “We also don't expect a big economic impact from the Delta variant in the US and Europe, economies with abundant vaccine supply and relatively permissive covid policies. Despite a rising number of breakthrough infections, the vaccines remain highly effective in preventing severe disease, so people who want to protect themselves against bad outcomes can do so and then mostly go about their lives. And while only half the US population is fully vaccinated, the holdouts don’t seem to worry enough to change their behavior in response to outbreaks.”

“Frontier Knowledge and Scientific Production: Evidence from the Collapse of International Science” - Alessandro Iaria, Carlo Schwarz, Fabian Waldinger | “We show that World War I and the subsequent boycott against Central scientists severely interrupted international scientific cooperation. . . . This suggests that access to the very best research is key for scientific and technological progress.”

Why Has Nuclear Power Been A Flop? - Jason Crawford, The Kernel | “Overcautious regulation interacted with economic history in a particular way in the mid–20th century that played out very badly for the nuclear industry.”

“Non-Disclosure Agreements and Externalities from Silence” - Jason Sockin, Aaron Sojourner, Evan Starr | “Together, our results highlight how firms can use broad NDAs to preserve their reputation by silencing workers, but that doing so imposes negative externalities on job seekers who value such information and on competing ‘high-road’ employers who are less able to distinguish themselves.”

Where Are The Robotic Bricklayers? - Brian Potter, Construction Physics | “Masonry seemed like the perfect candidate for mechanization, but a hundred years of limited success suggests there’s some aspect to it that prevents a machine from easily doing it. This makes it an interesting case study, as it helps define exactly where mechanization becomes difficult - what makes laying a brick so different than, say, hammering a nail, such that the latter is almost completely mechanized and the former is almost completely manual?”