⤴ In defense of 'cornucopianism' and a more populous planet

Also: 5 Quick Questions for … economist Parker Rogers on FDA regulation

“On what principle is it that, when we see nothing but improvement behind us, we are to expect nothing but deterioration before us?" - Thomas Babington Macaulay

The Essay

⤴ In defense of 'cornucopianism' and a more populous planet

It’s no easy task to select just one wrong-headed assertion among so many in the Scientific American essay “Eight Billion People in the World Is a Crisis, Not an Achievement” by Naomi Oreskes, a science historian at Harvard University. But here goes (bold by me):

Consider a recent Washington Post editorial saying eight billion people is “probably a good thing.” The authors' reasoning: Population has “more than doubled since 1968, and living standards around the world have vastly, though unevenly, improved.” With an ever increasing population, the editorialists write, “millions of new people—with their new ideas and fresh energy—are on the way,” and this will spur innovation that will solve our problems. … It's both counterfactual and illogical to imagine that more people will solve the problem of too many people. Most population growth is occurring in poor countries, where most people lack educational opportunities that might enable them to develop the kinds of ideas and skills they would need to apply their “fresh energy.” And, as the biodiversity agreement makes clear, the issue isn't just living standards as measured by per capita income. It's also quality of life, which is threatened by widespread degradation and destruction of nature.

One of those “poor countries” that Oreskes is referring to must be India. With a per capita GDP of around $2500, it certainly qualifies as poor. What’s more, no nation is expected to add more to the global population, some 250 million new humans, than India over the next three decades, according to the United Nations. Yet is it also possible that India might contribute some innovative energy and ideas to the global stock of energy and ideas in the future?

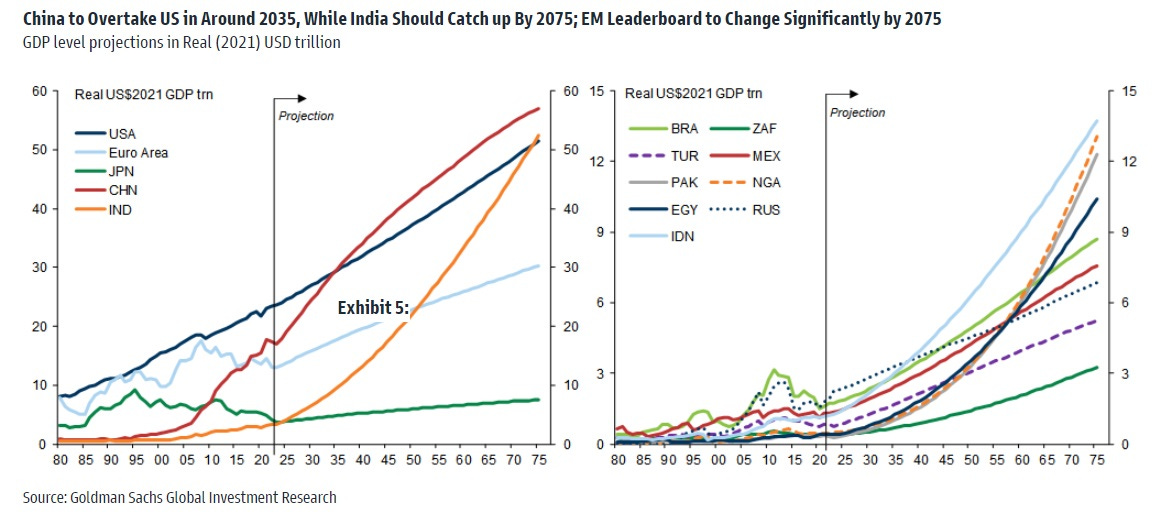

Oreskes might not think so, but I suspect it will. And I’m not alone. Goldman Sachs forecasts that India will be the world’s second-largest economy by 2075 with a real per capita GDP of $31,000, or about the same as Italy and Korea today. And as The Economist recently concluded, India’s “economy is growing strongly and India is good at nurturing entrepreneurial software engineers whose skills increasingly apply in every industry.”

Or as Microsoft President Brad Smith said last year, “India has made an extraordinary leapfrog move digitally in the global economy. It has probably made about five years of digital progress in the last 24 months. … India has long been one of the world's major sources of talent or the software field, a great creator of software IP. I think India is now well positioned to become one of the greatest data capitals of the world and double down on the status.” And here’s Patrick Vallance, chief scientific Adviser to the UK government: “India today is firmly on the path to being a science superpower.”

Population worriers never see potential, only problems. They always think the wrong sorts of people are having too many babies. This is how Paul “The Population Bomb” Ehrlich opens the first chapter of his book:

I have understood the population explosion intellectually for a long time. I came to understand it emotionally one stinking hot night in Delhi a couple of years ago. My wife and daughter and I were returning to our hotel in an ancient taxi. The seats were hopping with fleas. The only functional gear was third. As we crawled through the city, we entered a crowded slum area. The temperature was well over 100, and the air was a haze of dust and smoke. The streets seemed alive with people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing, and screaming. People thrusting their hands through the taxi window, begging. People defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people. As we moved slowly through the mob, hand horn squawking, the dust, noise, heat, and cooking fires gave the scene a hellish aspect. Would we ever get to our hotel? All three of us were, frankly, frightened. It seemed that anything could happen — but, of course, nothing did. Old India hands will laugh at our reaction. We were just some overprivileged tourists, unaccustomed to the sights and sounds of India. Perhaps, but since that night I've known the feel of overpopulation.

Let me offer another view: Economic growth — a greater ability to turn our dreams into reality — is driven by people discovering new ideas. “Other things equal, a larger population means more researchers which in turn leads to more new ideas and to higher living standards,” explains economist Charles I. Jones in “The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population.” And it’s my guess that the more smart humans we have — assisted by smarter and smarter tech and operating in a basic environment of economic freedom — the faster tech progress and economic growth will be, benefitting all of us.

Apparently, Oreskes sees things differently: “We ought to have a plan for slowing the destructive surge in human population.” Setting aside demographic trends that show global population plateauing by century’s end, past plans for slowing population growth provide ample reason for concern here. While Oreskes mentions giving girls and women greater access to education to slow population growth — a good thing but one that would seem to undermine her point about the global impoverished being forever and always unable to contribute to global progress and growth — it’s also certainly worth mentioning how past population degrowthers weren’t against coercive methods. “Coercion in a good cause,” as Ehrlich put it.

I would guess Oreskes would lump my views into “cornucopianism,” a term she uses in the essay, linking to this encyclopedia definition: “cornucopian, label given to individuals who assert that the environmental problems faced by society either do not exist or can be solved by technology or the free market.” Oreskes:

This [abundance] argument is a retread of a theoretical framework that was named cornucopianism in the 1980s. Cornucopians, led by economist Julian Simon and military strategist Herman Kahn, argued that anxiety over limited natural resources is misguided because human ingenuity can overcome any limits. Let populations grow alongside markets operating under minimal government constraints, and people will invent solutions to whatever problems they face.

I dunno, this all strikes me as a clumsy attempt to discredit opponents as a bunch wild-eyed, extreme libertarians. Most of the pro-progress folks I know certainly see a role for government, from a safety net to funding basic science, if not more. But they also think human ingenuity and entrepreneurship has a pretty good track record when it comes to solving big problems. Weird, I would think a historian would know this.

5QQ

💡 5 Quick Questions for … economist Parker Rogers on FDA regulation

In an excellent recent paper that generated some buzz among the social media accounts that I closely follow, “Regulating the Innovators: Approval Costs and Innovation in Medical Technologies,” Parker Rogers, (a PhD candidate in economics at the University of California, San Diego) looks at the effects of FDA regulation on medical device innovation, market concentration, and safety by examining FDA "down-classification." When the FDA reclassifies a medical device from high regulation to moderate regulation, Rogers finds, "the quantity and quality of new technologies in affected medical device types" increase significantly, while "rates of serious injuries and deaths attributable to defective devices" do not. Here is the full abstract:

How does FDA regulation affect innovation and market concentration? I examine this question by exploiting FDA deregulation events that affected certain medical device types but not others. I collect comprehensive data on medical device innovation, device safety, firm entry, prices, and regulatory changes and enhance these data using text analysis methods. My analysis of these data reveals three key findings. First, deregulation events significantly increased the quantity and quality of new technologies in affected medical device types relative to controls. These increases are particularly strong among small and inexperienced firms. Second, these events increased firm entry and reduced prices for medical procedures that utilize affected medical device types. Finally, rates of serious injuries and deaths attributable to defective devices did not significantly increase following these events. Interestingly, deregulating certain device types was associated with reduced adverse event rates, possibly due to firms increasing their emphasis on product safety in response to increased litigation risk.

It's a fascinating paper, so I emailed Rogers to find out more.

1/ How do you think about the balance between FDA regulation and legal liability for medical producers?

Federal preemption protects medical producers from liability risks when their product receives FDA approval. This protection raises an important question for policymakers: Does regulation or litigation best encourage innovation and ensure product safety? My research suggests that legal liability can best accomplish both objectives.

2/ How would you respond to someone who claims that more FDA regulations are necessary because they increase consumer confidence in a product?

While regulatory approval does seem to increase the use of existing technologies, it also imposes significant costs that restrict the emergence of other potentially life-saving innovations. Further, there are other ways to build consumer confidence, such as providing warranties, which some drug companies already do. Even without warranties, consumers often opt into using medications in ways that are not FDA-approved, showing that consumer confidence can exist without regulation.

3/ Should we be concerned about moral hazard associated with FDA approval among consumers?

Consumers and producers both face a moral hazard, where consumers may not proactively seek safer or more effective products, instead relying solely on FDA information, and producers may prioritize meeting FDA requirements with less regard for patient safety. Additionally, some doctors may rely on the FDA guidance instead of tailoring treatments to individual patient needs.

4/ To what extent do the costs of regulations deter producers from medical product R&D?

My research on medical devices shows that regulatory barriers can deter medical product R&D by as much as 400 percent, depending on the types of regulations. It’s concerning that, despite our ability to have intelligent conversations with computers, we are still grappling with routine illnesses and diagnostic errors. I wouldn’t be surprised if the current regulatory framework plays a crucial role in this discrepancy.

5/ Do your findings apply to regulations in other industries?

Regulatory compliance provides a degree of legal protection for a wide range of products, including drugs, medical devices, GMOs, aircraft, automobiles, pesticides, and more than 15,000 consumer products overseen by the Consumer Product Safety Commission. My findings help highlight the potential tradeoffs of regulating technologies in these and other industries.

Micro Reads

▶ Beyond Catastrophe: A New Climate Reality Is Coming Into View - David Wallace-Wells, NYT |

▶ Vaccines based on mRNA need to get out of the freezer - The Economist |

▶ Man beats machine at Go in human victory over AI - Richard Water, FT |

▶ Hyperloop Dreams Endangered After SPAC Deal Fails - Sarah McBride, Bloomberg |

▶ Microsoft flip-flops on reining in Bing AI chatbot - Gerrit De Vynck, WaPo |

▶ We Can Vacuum Carbon From the Sky. Will It Make a Difference? - Lara Williams, Bloomberg Opinion |