🤔 Imagine an America with steep billionaire taxes — and without Amazon, Pixar, SpaceX, and Tesla (essay repost)

I shudder at the thought! And you should, too!

In his State of the Union address last night, President Joe Biden revisited the idea of a special tax on billionaires. So given that recycled proposal — and the fact that I’m sick — I thought it would be a good time for a rare Faster, Please! repost of a relevant essay from last March on the subject. (Fun Bonus: It includes an Elon Musk tweet response to me!)

🧐 Imagine an America with steep billionaire taxes — and without Amazon, Pixar, SpaceX, and Tesla

Item: President Joe Biden will propose a minimum 20% tax rate that would hit both the income and unrealized capital gains of U.S. households worth more than $100 million as part of his budget proposal to be released on Monday. … The administration projects that more than half of revenues for the new payment would come from the nation’s roughly 700 billionaires. (Bloomberg, March 26, 2022)

Two reasonable questions to ask about any public policy idea: First, what problem is the idea meant to solve or ameliorate? Second, what are the trade-offs? (Getting one thing typically means giving up another.) And the answers to both those questions make me queasy about ongoing efforts to “capture” more of the income and wealth of America’s richest people, especially those who got that way by starting and building great companies.

Talking (wealth and income) taxes

Let’s start with that first question. Whether we’re talking about Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax from her 2020 presidential campaign or President Joe Biden’s new billionaire tax, the main problems that these plans are supposedly attempting to address are revenue generation and tax fairness. To be sure, those are issues about which I’m also concerned. But I think it’s a mistake to not be equally concerned — perhaps even more so — about how the current tax code encourages or discourages productive economic activity. Likewise, we must consider how changes in tax policy affect business innovation and investment.

Which brings us to the second question: Might these efforts to raise revenue and reduce inequality generate wholly undesirable trade-offs and numerous unintended consequences — especially when it comes to business innovation and economy-wide productivity growth? After all, the reason I write this newsletter is because of my deep concern about decades of lagging science progress, technology invention, and business innovation.

The Elon Musk entrepreneurial empire: a case study

I think my concerns are reasonable. Take the case of the Biden administration’s version of "He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named" — or named only rarely — Elon Musk. Remember, he’s not just an uberbillionaire with dodgy Twitter behavior. He's also an immigrant who both resurrected the American space industry and grew an electric auto company that makes him, as his Time magazine Person of the Year profile puts it, “arguably the biggest private contributor to the fight against climate change.”

But would SpaceX and Tesla — combined value of an estimated $1.2 trillion — exist in a world of sharply higher investment taxes and a fat new levy on wealth? Maybe not. At least not both of them.

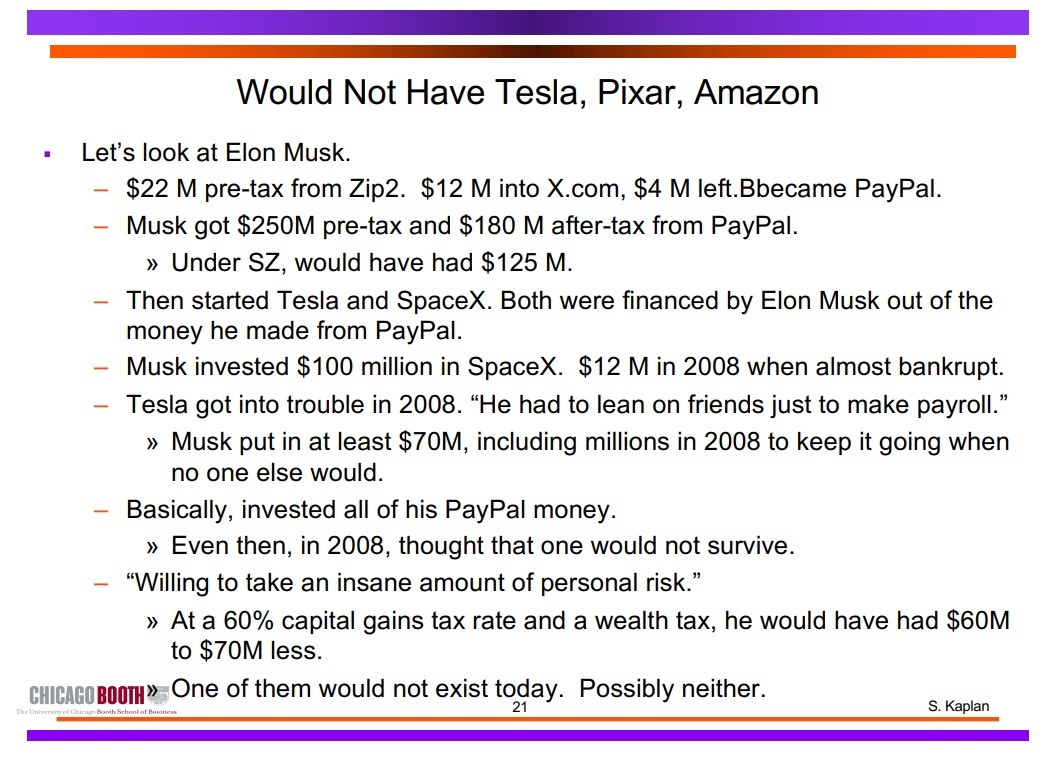

University of Chicago economist Steven Kaplan has run the numbers. To begin: Musk was one of the “PayPal Mafia,” the founders and early employees of the financial technology company. When PayPal was bought by eBay in 2002, Musk, the largest shareholder, walked away with $250 million before taxes, leaving him with $180 million after taxes.

What did Musk do with that cash? Well, he didn’t buy some monstrous Bel-Air mansion or pricey Picasso painting. Instead, he started SpaceX in 2002, putting in $100 million, and Tesla in 2003, putting in $80 million. Musk: “I thought the probability of success was so low that I provided all of the money. All of the money just came from me personally. I didn't want to ask people, other investors for money if I thought we were going to die because I thought we were.”

Of course, it’s hardly been a smooth ride getting from there to here. In 2008, during the Global Financial Crisis, both companies almost went bankrupt. Musk calls it “definitely the worst year of my life.” Tesla closed a financing round on Christmas Eve 2008. “It was the last hour of the last day that it was possible,” he recalled in 2015. “Even then, we only narrowly survived.”

As for SpaceX, here’s a bit from a December 2021 podcast chat I had with Eric Berger, senior space editor at Ars Technica and the author of Liftoff: Elon Musk and the Desperate Early Days That Launched SpaceX:

By far, the most desperate moment for SpaceX was after the third flight of the Falcon 1 rocket where pretty much everyone assumed they were going to be successful. They were already running out of money. And then that rocket went up and failed. That was the summer when Elon Musk was getting divorced, where Tesla was hemorrhaging money. And now SpaceX had just failed for the third time. [SpaceX President] Gwynne Shotwell said they had payroll for maybe six or eight more weeks, then the company was going to go bust.

And so that was a desperate period when they were leading up to the launch and they had one more rocket, the fourth rocket they were going to launch, and they were flying it out to [the Kwajalein Atoll launch site in the Marshall Islands]. ... And as they were flying that first stage toward Kwajalein, it starts imploding on the C-17 aircraft. And so this was their last piece of hardware. So that was probably the most desperate moment when everyone on that plane thought they might die due to that imploding rocket. And then they were also concerned about losing the hardware. They were able, obviously, to salvage it.

Indeed, they did. That historic fourth flight on September 28, 2008 made the Falcon 1 the first privately built liquid-fueled booster to reach orbit. It saved the company. But would that launch have happened if Musk had left PayPal with $60 million less? Would Tesla have muddled into 2009 and beyond? Kaplan doesn’t think so. “Either SpaceX or Tesla would not exist — and I don’t think anyone else would have done it,” he said in a 2020 debate with University of California, Berkeley, economist Emmanuel Saez, a wealth tax proponent.

Interregnum: Kaplan’s analysis here is of a plan by Saez and Gabriel Zucman that was the basis of the Warren wealth tax. I would note, however, that the Biden plan is also a significant tax, estimated to raise some $360 billion over a decade. It might also require some wealthy entrepreneurs to sell lots of stock. As The Washington Post explains: “The White House tax plan would dramatically change what some of the wealthiest Americans pay in taxes. Tesla chief executive Elon Musk would pay an additional $50 billion, while Amazon founder Jeff Bezos would pay an additional $35 billion, according to calculations by Zucman, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley.”

Update: Elon agrees:

No Amazon Prime, no Woody and Buzz

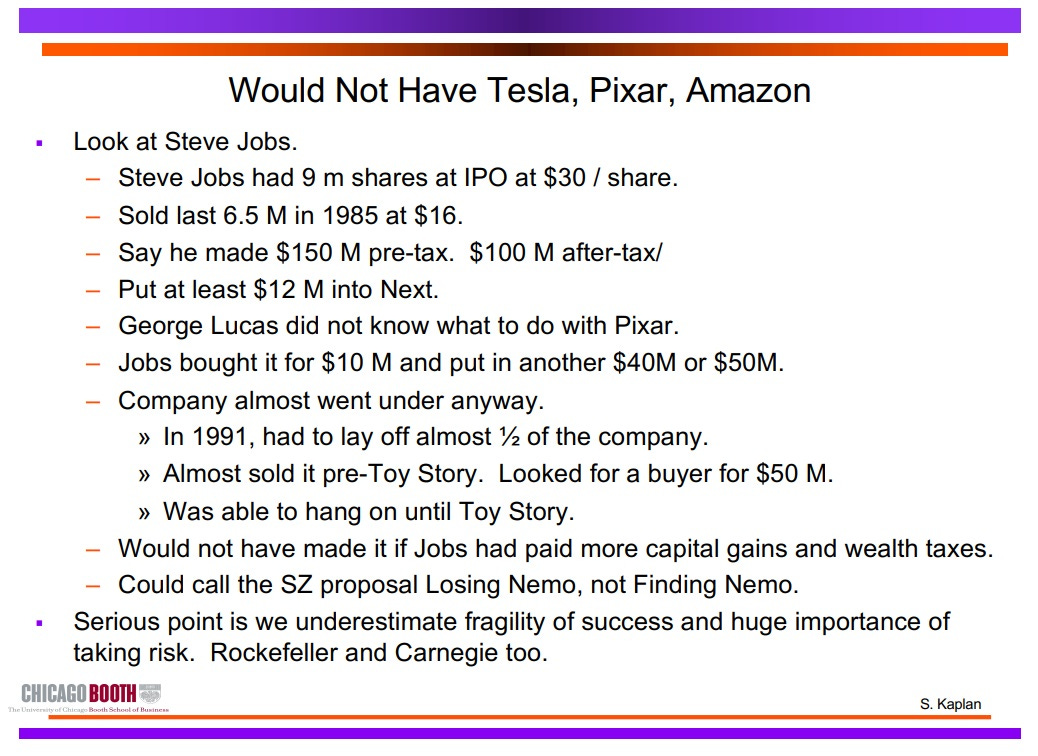

What’s more, much the same case can be made for Amazon and Pixar as for Tesla/SpaceX. Kaplan:

Steve Jobs got his money from Apple, he left Apple, and he put a big chunk of it into Pixar. It also almost went bankrupt, it didn’t, and if you had taxed him more, he would have had to have sold Pixar. It wouldn’t have been Pixar. So you know what I would say there is that you would have “Losing Nemo” instead of “Finding Nemo.”

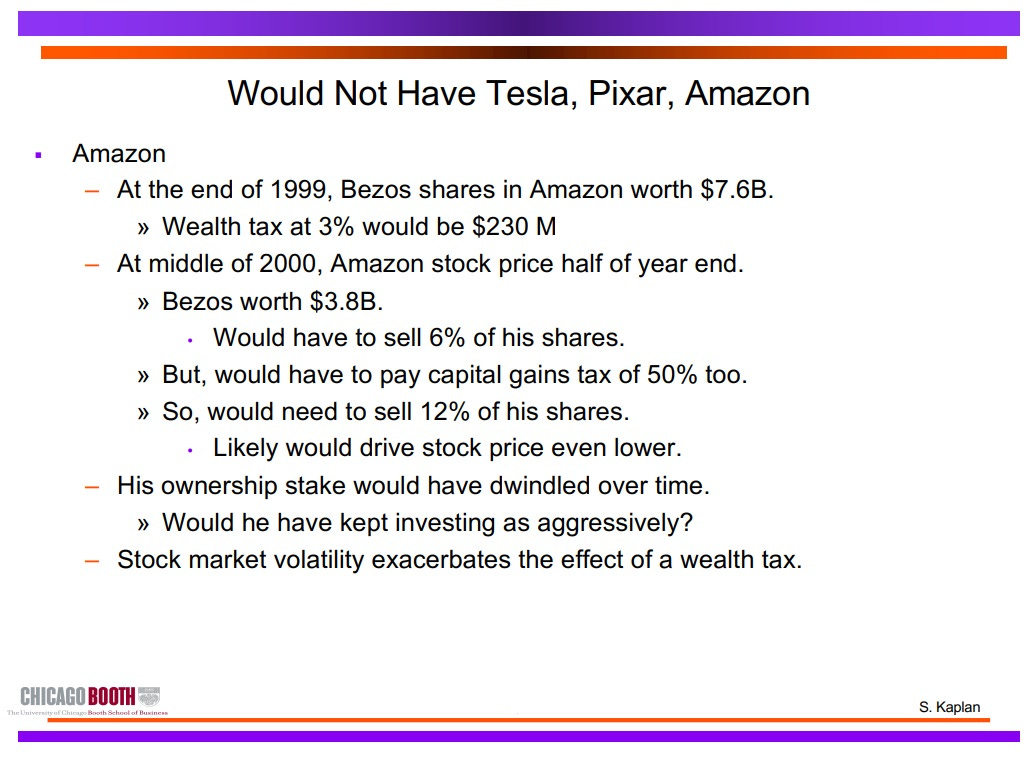

Jeff Bezos was worth $4.7 billion or $5 billion in 2000. At the peak of the dotcom bubble, Amazon hadn’t really succeeded then. And if you imposed a 5 percent wealth tax on him when it was 5 billion, that’s a $250 million tax. By the time he would probably get around to paying it, which would be June [of 2000], his shares were worth 2.5 billion [due to the plunging stock market]. So now he’s got to sell. To get the 250 million – he would have to sell 10 percent of his shares. But then we [also] have a 50 percent capital gains tax. Got to sell 20 percent of [the] shares. So in six months, under this plan, he would have to sell 20 percent of Amazon in that situation. Which would probably – what would that do to the stock price? Probably drive it down further. So maybe 25 percent of Amazon. Do you want Jeff Bezos to be selling 25% of Amazon? In 2000?

No such a thing as a free lunch or free Amazon Prime

So, trade-offs. And if you are a labor activist who doesn’t like Amazon, an astronomer who doesn’t like SpaceX and all the satellites it puts in the night sky, or an old-school cartoon buff who loves the traditional 2-D animation that Pixar killed, maybe a world without those companies is a better world. That lunch is a great bargain!

As for me, however, I like a world that includes those companies and the valuable products and services (and toons) they provide. But understanding the potential trade-offs is necessary no matter where one stands.

And for my readers who might like to still sock it to the billionaires, one final point: According to estimates by Nobel laureate economist William Nordhaus, innovators captured only 2 percent of the value they created between 1948 and 2001. He found that “only a miniscule fraction of the social returns from technological advances” accrued to innovators and concluded that “most of the benefits of technological change are passed on to consumers.” I would guess an update analysis would be similar. Indeed, I wrote last April about how most of the value created by Bezos and Amazon doesn’t go to Bezos.

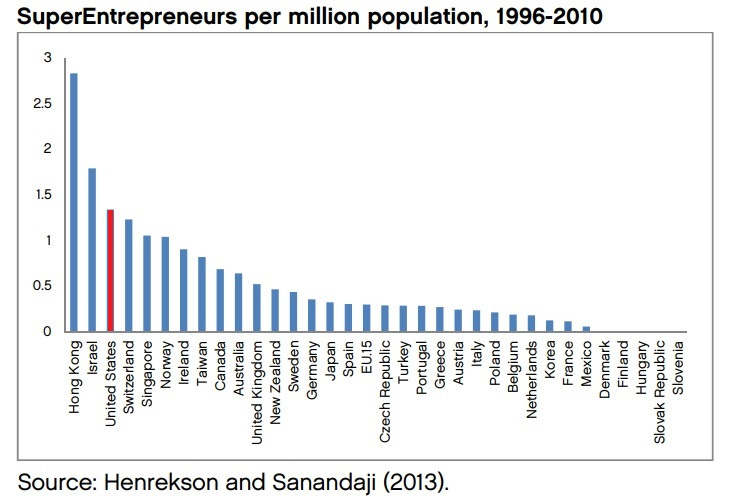

A 2019 Economist piece speculated that an understanding of Nordhaus’s point is why “billionaires are tolerated even by countries with impeccable social-democratic credentials: Sweden and Norway have more billionaires per person than America does.” If only more American policymakers possessed similar insight.