🤖 From Hollywood studios to West Coast ports, automation fears are sweeping through the US economy

Also: 5 Quick Questions for … federal science funding analyst Matt Hourihan

Quote of the Issue

“Three generations of working Englishmen were made worse off as technological creativity was allowed to thrive. And those who lost out did not live to see the day of the great enrichment. The Luddites were right, but later generations can still be grateful that they did not have it their way. History is made in the short run because the decisions we make today shape the long run. Had the Luddites been successful in bringing progress to a halt, the Industrial Revolution would probably have happened somewhere else. And if not, economic life would most likely still look similar to the way it did in 1700.” - Carl Benedikt Frey, The Technology Trap

The Essay

🤖 From Hollywood studios to West Coast ports, automation fears are sweeping through the US economy US economy

Hollywood creative types and dockworkers at the nearby Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles may not seem to have much in common. But both groups have been involved in labor strikes where automation of one sort or another has been a key issue of contention between union members and their employers. Writers and actors fear AI-generated scripts (and eventually, perhaps, entire films) due to recent advances in generative AI, while longshoremen see an ongoing threat to good-paying jobs from robots: automated cranes and self-driving vehicles.

Indeed, both groups portray the threat as ultimately an existential one. As comedy writer Miranda Berman told NPR, “This is only the beginning; if they take writer's jobs, they'll take everybody else's jobs too. And also in the movies, the robots kill everyone in the end.” Harold Daggett, head of the International Longshoremen’s Association, said in a video last year, “They want to put automation in and eliminate us, that’s what it is all about.”

All of this has happened before and will happen again

Such fears of massive job disruption are hardly founded. Technological progress has always brought big changes for workers, some of it unpleasant. The postwar automation wave, including the innovation of shipping containers, reduced longshoremen employment by 90 percent, although workers today are better paid and trained.

Likewise, the arrival of computer-generated imaging in the late 1980s and 1990s had a big impact on special-effect artists and animators, though perhaps more on how they did their work than the absolute number of jobs. From a Quartz piece back in 2016:

The tipping point came in 1993 with Steven Spielberg’s dinosaur thriller, Jurassic Park. According to the New Yorker, Spielberg put two separate teams on dinosaur design: one using old-fashioned stop-motion techniques, one on digital. The head of the go-motion team saw the digital team’s flawlessly rendered Tyrannosaurus Rex and reportedly deadpanned, “I think I’m extinct.”

But while CGI shifted special-effects work to digital over animation, it also created jobs. As I noted recently, there were 36,000 “Special Effects Artists and Animators” jobs in the US in 2022, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, versus 26,000 back in 2006 when Disney bought Pixar, eventually shuttering its hand-drawn animation studio in Orlando, Florida.

A similar phenomenon can be seen in port automation. While there may be many fewer longshoremen — and basically none remaining who work the way the stevedores did in prewar America — port innovation also created jobs in the broader economy by boosting port efficiency and expanding global trade. A 2020 St. Louis Fed analysis found that from 1970 through 2018, a) total world total exports grew tenfold, b) the share of internationally traded goods and services increased from less than 14 percent of global GDP to more than 30 percent, and c) the ratio of US exports to GDP increased from 5.6 percent to 12.2 percent.

From the analysis: “A key factor spurring this rapid globalization was the pervasive adoption of containers and corresponding infrastructure, which led to drastic cost reductions for transporting goods.”

Technology doesn’t just replace workers, you know

A basic question about the economic history of technology and work: Why are there still so many jobs? Or as MIT economist David Autor asks in his 2015 paper on technological unemployment, “Why doesn’t automation necessarily reduce aggregate employment, even as it demonstrably reduces labor requirements per unit of output produced?”

First, automation has two effects: it replaces some workers, but it also helps others become more productive or creates entirely new things for humans to do. Second, some tasks are hard to do with machines. (“The tasks that have proved most vexing to automate are those demanding flexibility, judgment, and common sense—skills that we understand only tacitly.”) Third, automation may lower costs and thus boost demand for goods and services.

But won’t AI eventually — and maybe sooner rather than later — render obsolete that Econ 101 answer? History suggests not, even fairly recent history. In a 2019 paper, “The Occupational Impact of Artificial Intelligence: Labor, Skills, and Polarization,” economists Edward Felten, Manav Raj, and Robert Seamans create a new measure to gauge the impact of specific AI applications — such as image recognition, translation, or the ability to play strategic games — on real-world job tasks and occupations. They conclude: “We provide evidence that, on average, occupations impacted by AI experience a small but positive change in wages, but no change in employment.”

Past performance doesn’t guarantee future results, of course. So Autor offers some good news, just in case AI really does make this time different:

A final point, typically neglected in recent dismal prophesies of machine-human substitution, is that if human labor is indeed rendered superfluous by automation, then our chief economic problem will be one of distribution, not of scarcity. … If machines were in fact to make human labor superfluous, we would have vast aggregate wealth but a serious challenge in determining who owns it and how to share it. … Are we actually on the verge of throwing off the yoke of scarcity so that our primary economic challenge soon becomes one of distribution? Here, I recall the observations of economist, computer scientist, and Nobel laureate Herbert Simon (1966), who wrote at the time of the automation anxiety of the 1960s: “Insofar as they are economic problems at all, the world’s problems in this generation and the next are problems of scarcity, not of intolerable abundance. The bogeyman of automation consumes worrying capacity that should be saved for real problems . . .” A half century on, I believe the evidence favors Simon’s view.

Not that Hollywood writers or West Coast dockworkers should find tremendous immediate comfort in any of what I’ve written. Change is going to come. It did for the dockworkers of old, though that change was softened by a labor agreement where displaced workers received generous payments. Perhaps the epilogue to that automation battle will repeat this time around. As recounted in The Atlantic:

Harry Bridges, who was the president of the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union from 1937 to 1977, was among the first labor leaders to bargain explicitly with management on the consequences of automation. Beginning in 1960, as the West Coast docks were automated, Bridges negotiated the following arrangement: The shipping companies would be free to automate, but his members would not be laid off. The wages of longshoremen holding "A" union cards would rise with productivity, and the number of longshoremen would gradually be reduced by attrition. Bridges liked to say, "At this rate, by the year 2000 there will be one longshoreman left on the docks. But he's going to be the best paid son of a bitch in the United States."

As for Hollywood, folks who embrace AI may not get as much attention as picketers with clever and snarky signs (“AI? MORE LIKE AI-YI-YI!”) but they’re out there, which provides hope for use cases that favor complementation rather than just automation. From NBR:

"I'm using it as a brainstorming tool and as a research aide," says TV writer Matt Nix, who tested several AI programs to give him episode ideas for his show True Lies. … Nix says when it comes to generating ideas, if you make a single request, an AI program is likely to spit out the most cliched version of what it's seen before. "But if you play with it and you say, 'no, no, I don't want just one idea for this. I want five ideas for this,' then it has to dig a little bit deeper and give you the less likely ideas."

Nix has been playing around with an AI app called Pickaxe, which was built by Mike Gioia and Ian Eck, who run a film and media production company. They presented their work this week at a summit called "AI On the Lot." With Pickaxe, writers can generate written scenes by describing their plots and characters in a text box. Gioia says screenwriters have told them it's a helpful tool "to do 80 percent of the work for them, like get around writer's block, generate a B-minus version of a scene or conversation that they can then spruce up. It's far away from being able to write screenplays."

The US economy and its workers need to be more productive. We more AI and more robots. We needs more technology that automates and more technology that complements and creates. Most of all, we need more imagination about how technology will benefit our lives.

5QQ

💡 5 Quick Questions for … federal science funding analyst Matt Hourihan

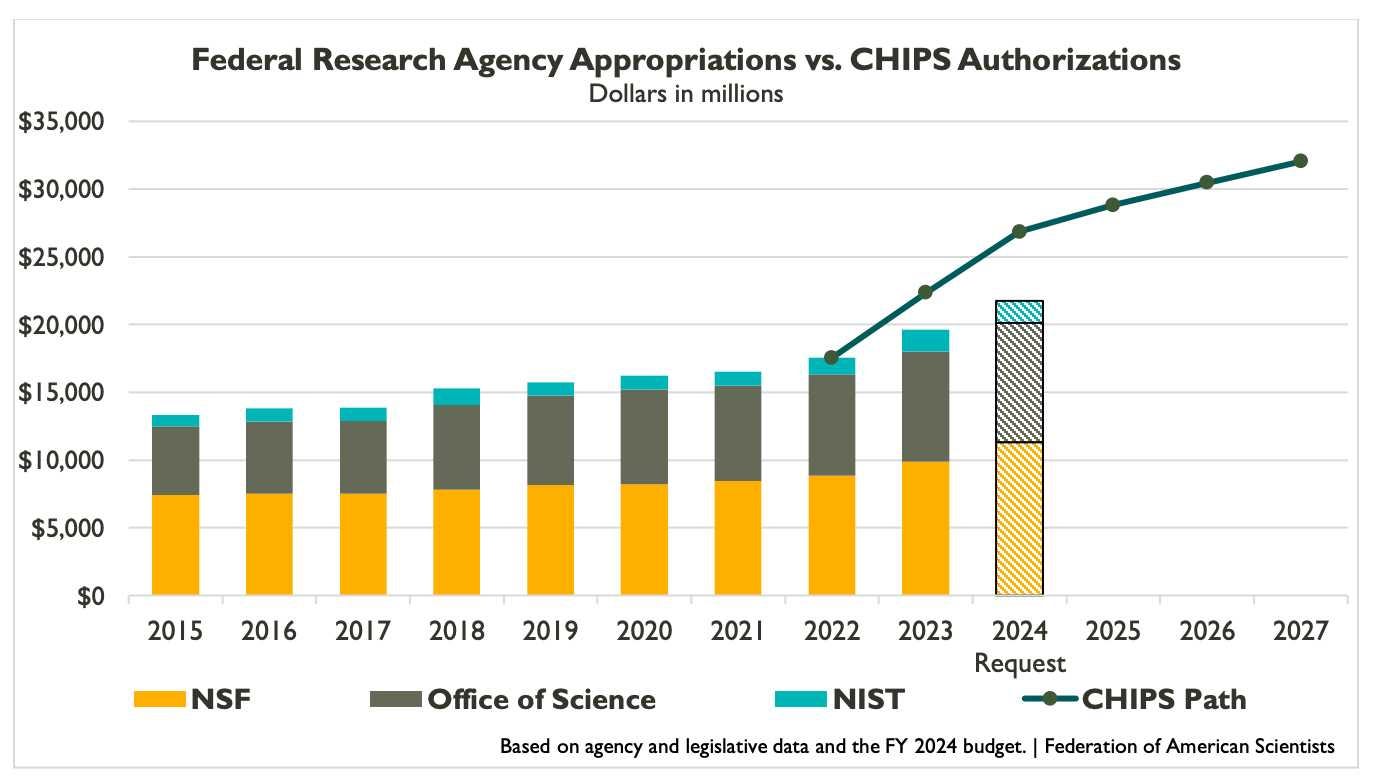

Matt Hourihan is associate director of R&D and Advanced Industry with the Federation of American Scientists. Earlier this year, Matt provided some 5QQ answers on his assessment of the CHIPS and Science Act, which authorized key science and R&D spending. But, as the recent budget negotiations over the debt ceiling demonstrate, Congress doesn’t always live up to its funding promises. So I’ve tapped Matt again to give an update on how the CHIPS and Science Act is doing.

1/ Before the recent budget deal between the White House and congressional Republicans, it seemed doubtful whether the CHIPS and Science Act would even receive the funding it was promised. Where do things stand now? Can you put the current funding gap in context?

Beyond the mandatory $54 billion for semiconductors and wireless innovation, CHIPS and Science authorized a multi-year funding ramp-up for the National Science Foundation, the Office of Science, and NIST, along with a clutch of other activities in energy R&D and regional innovation. This has all mostly been underfunded from the jump. For the research agencies, the FY 2023 omnibus provided some boosts, but those increases were still short of the authorized level for research agencies by about $3 billion excluding earmarks. The FY 2024 White House request continued to undershoot the targets. Now with the discretionary caps, it vastly limits federal ability to pursue the tech priorities established in CHIPS. We can already see the effect in the new House energy bill, which flat-funded or cut several basic and applied research offices at the Department of Energy.

2/ Some provisions of the CHIPS and Science Act seem to be at greater risk of coming up short on authorized funds than others. Which areas have received closest to authorization-level funding?

There are scattered programs here and there that have gotten pretty close, or even surpassed, their authorized levels. For instance, NSF’s Noyce teacher scholarships, DOE Biological and Environmental Research, and DOE High Energy Physics. In some cases, where the gap isn’t so big, it may be because of a funding boost, or because the authorization was more modest, or (in case of NIST) because Congress attached earmarks or “community project funding” to a funding account.

3/ Previously you noted that "the House is talking about rolling back nondefense spending in a such a way that it would kneecap our ability to invest." How greatly will the cuts to nondefense discretionary spending affect CHIPS and Science funding this year and in coming years?

We dodged the worst-case scenario in the original House debt ceiling bill, but we still haven’t made it easy on ourselves. Unless Congress can come up with a workaround, the caps mean perhaps a $16 billion shortfall below CHIPS targets and a squeeze on agencies, and specific priorities will probably go un- or under-funded. For instance, agencies have proposed ramping up R&D in microelectronics, in biotechnology, and DOE is looking to expand fusion technology partnerships with industry. The regional tech hubs are mostly unfunded. These are areas prioritized in CHIPS where the US is trying to gain or sustain competitive advantage, and the spending limits mean a lot of these investments may not happen. We’re a long way from the original $100 billion vision.

4/ Given the long-term nature of R&D, should federal science spending be mandatory rather than discretionary?

I think it could make enormous sense to have some sort of mandatory stream for critical technology R&D, to supplement annual appropriations. If done right it could provide a level of stability for science investments, which benefit from predictability, in the face of the funding swings we seem to have every few years. You wouldn’t want these to displace base appropriations, which would defeat the purpose. You could gear it towards R&D in critical technologies, or toward stable R&D capital investments.

5/ What do we know right now about CHIPS and Science funding and what's still unknown?

Focusing on the “and Science” portion, we’ve got annual appropriations settled for year one out of five, spending caps in place for the next two years at least, an upcoming presidential election, deep divisions over broad fiscal policy, continuing bipartisan interest in science and innovation, a Senate desire to draft and adopt another competitiveness bill, and six weeks in session before a potential shutdown. So there’s a lot we don’t know! But agencies are moving to implement what they can with the resources they have, and I hope Congress can figure out a way to navigate all this and make new investments.

Micro Reads

▶ The working-from-home illusion fades - The Economist |

▶ Super Mario Meets AI: Experimental Effects of Automation and Skills on Team Performance and Coordination - Fabrizio Dell'Acqua, Bruce Kogut, and Patryk Perkowski, MIT |

▶ AI has secured a footing in drug discovery. Where does it go from here? - Michael Gibney, PharmaVoice |

▶ A Dog’s Life Could Hold the Key to Anti-Aging Drugs for Humans - Gideon Lichfield and Lauren Goode, Wired |

▶ The nuclear industry’s big bet on going small - Umair Irfan, Vox |

▶ Virgin Galactic Reaches Space in Overdue Commercial Debut - Loren Grush, Bloomberg |

▶ Air Pollution Is Deadlier Than You Think - Charles Swanton, Wired |

▶ US is on track to halve emissions by 2035, but this still isn't enough - James Dinneen, New Scientist |

▶ Microsoft and Nvidia join $1.3bn fundraising for Inflection AI - Madhumita Murgia, FT |

▶ Capitalism unchained - Branko Milanovic, Global Policy |

▶ The choice between a poorer today and a hotter tomorrow - The Economist |

▶ Me, Myself, and AI - Allison Whitten, Stanford Magazine |

▶ AI is supposedly the new nuclear weapons — but how similar are they, really? - Dylan Matthews, Vox |

▶ No more ‘playing God’: How the longevity field is trying to recast its work as serious science - Jason Mast, STAT |