💥 Four shocking truths about the American economy! (Well, shocking to some.)

What you may have heard about productivity and pay, wage growth, income inequality, and upward mobility might be wrong. Way wrong.

Quote of the Issue

“Our ability to crystallize imagination is the ability to create objects that were born as works of fiction. The airplane, the helicopter, and Hugh Herr’s robotic legs were all thoughts before they were constructed. Our ability to crystallize imagination sets us apart from other species, as it allows us to create in the fluidity of our minds and then embody our creations in the rigidity of our planet.” - César A.Hidalgo, Why Information Grows: The Evolution of Order, from Atoms to Economies

I have a book coming out on October 3, 2023. The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised is currently available for pre-order pretty much everywhere, including Amazon. I’m very excited about it!

The Essay

💥 Four shocking truths about the American economy!

I recently wrote a brief essay, “Generative AI and Economic Growth,” for Exponential View, the great newsletter by Azeem Azhar. And I knew one particular passage would be sure to raise eyebrows:

A lengthy and fundamentally solid expansion would allow the economic progress of the pre-pandemic period — falling inequality, rising real wages across the income spectrum — to kick back into gear.

See, there’s a group of economic beliefs that I see confidently and repeatedly stated across traditional and social media: inequality is rising, wages are stagnant, upward mobility is dead, and productivity growth is disconnected from pay growth. In short: Capitalism, especially American-style, “cowboy” or “cutthroat” capitalism isn’t working today and hasn’t worked for decades, really.

And while I never try to be contrarian just for the sake of being contrarian, I take a starkly different view on all of those issues. Time for some myth busting, Faster, Please! style!

“The link between productivity and worker pay is broken.” It isn’t. You might have seen some version of this chart showing a long-term and massive divergence — like, by a factor of five — between productivity growth and wage growth:

“The Link Between Productivity and Wages Is Strong” by Michael R. Strain But this next chart tells a radically different story about productivity and pay, showing the two stats move together decade after decade with some modest divergence since 2000 — but nothing like disconnect seen in the first chart:

“The Link Between Productivity and Wages Is Strong” by Michael R. Strain There’s a reasonable argument to be made that the second chart more accurately reflects economic reality in its basic conceptual choices. Among them: Defining output as net output rather than gross output in this case — productivity is output per worker or hour of worker — makes sense since it removes capital depreciation. As AEI economist Michael Strain observes, “Since depreciation is not a source of income, net output is the better measure to use when investigating the link between worker compensation and productivity.

Second, it’s better to include non-wage compensation, including health benefits, rather than just wage compensation given that non-wage compensation has risen as a share of total worker compensation. “Contrary to the current narrative in some policy circles, the link between productivity and wages is strong,” Strain concludes.

“Income inequality continues to rise at an alarming rate.” Not at all. As I write in the EV essay, the Congressional Budget Office uses the Gini coefficient to estimate the income gap between higher- and lower-income households. Inequality of income after taxes and transfers — which unlike market income is a comprehensive measure of living standards that considers the impact of taxes and social transfers on people's economic well-being — increased by 7 percent from 1990 to 2019, but the rise happened only from 1990 to 2007. Inequality has decreased by 5 percent since 2007 when political and media attention to inequality surged in response to the GFC and the Occupy Wall Street protests. Here’s the CBO chart:

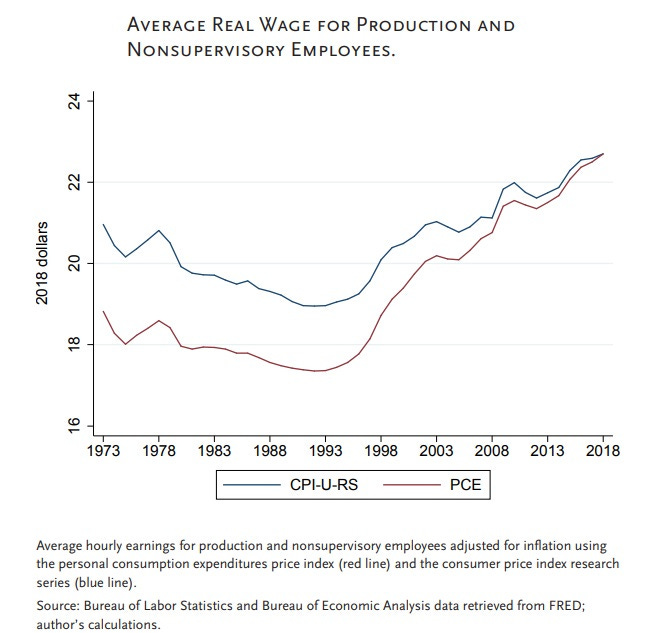

“Worker wages have gone nowhere for decades.” Think again. The most common version of this claim is that since the 1970s, wages haven't really gone up much at all — maybe just a teensy 5 percent increase since the Nixon presidency. But using that 5 percent number to sum up five decades of American economic history leads to a misleading claim about stagnation.

From the peak of the 1990 business cycle though 2019, real wages have actually gone up by a fifth using the consumer price index and by a third using the price consumption expenditure index, which the Federal Reserve prefers, according to Strain’s calculations.

The American Dream Is Not Dead: (But Populism Could Kill It) by Michael R. Strain And if we look at the bigger picture and check how much money people have after taxes and tranfers, the stagnation argument looks even worse. As the CBO noted in its recent look at incomes from 1979 through 2019:

- Over 41 years, all income groups saw highest average income after transfers and taxes in 2019.

- Income growth after transfers and taxes was fastest for top earners, but more even across the distribution due to progressive tax and transfer systems.

- The lowest quintile's income after transfers and taxes grew 94 percent (1.7% annually).

- The middle three quintiles' income after transfers and taxes grew 59 percent (1.2 percent annually).

- The highest quintile's average federal tax rate decreased, resulting in slightly faster growth in income after transfers and taxes (123 percent or 2.0 percent annually), reaching $252,100 in 2019 from $113,100 in 1979.

“Upward mobility is a thing of the past.” Oh, it’s still happening! Are people doing better in their 40s than their parents were doing during their 40s? Overall, Strain finds that around 73 percent of Americans in their 40s have higher incomes than did their parents. For kids raised in the bottom 20 percent, that number is 86 percent.

The American Dream Is Not Dead: (But Populism Could Kill It) - By Michael R. Strain

Now here’s the thing: While the above data may argue things are better than many Americans and econ pundits think, things could be better still. The whole point of this newsletter is to show a better tomorrow is possible if we make better decisions as a society. And one of those decisions to make sure our entrepreneurial and innovative market economy is firing on all cylinders — and appreciate the value of market capitalism as the best path we know to prosperity.

Micro Reads

▶ The AI boom: lessons from history - The Economist | AI might well augment the productivity of workers of all different skill levels, even writers. Yet what that means for an occupation as a whole depends on whether improved productivity and lower costs lead to a big jump in demand or only a minor one. When the assembly line—a process innovation with gpt-like characteristics—allowed Henry Ford to cut the cost of making cars, demand surged and workers benefited. If AI boosts productivity and lowers costs in medicine, for example, that might lead to much higher demand for medical services and professionals.

▶ Consciousness in Artificial Intelligence: Insights from the Science of Consciousness - Patrick Butlin, et al., Arxiv |

▶ China’s 40-Year Boom Is Over. What Comes Next? - Lingling Wei and Stella Yifan Xie, WSJ |

▶ The battle between American workers and technology heats up - Schumpeter, The Economist |

▶ More Autonomous Robots to Hit Farms With Manufacturer’s US Expansion - Tarso Veloso Ribeiro and Michael Hirtzer, Bloomberg |

▶ The renewable energy revolution is happening faster than you think - James Dineen, New Scientist |

▶ China hits the east Asian demographic wall - Gideon Rachmaan, FT Opinion |

▶ Lidar on a Chip Puts Self-Driving Cars in the Fast Lane - IEEE Spectrum |

▶ America’s Tech Giants Rush to Comply With New Curbs in Europe - Kim Mackrael - and Sam Schechner, WSJ |

▶ Deep-Sea Mining Could Begin Soon, Regulated or Not - Olive Heffernan, Scientific American |

▶ Why China remains hungry for AI chips despite US restrictions - Richard Waters and Qianer Liu, FT |

▶ We’re bad at predicting the future and there’s no way around it - Kelsey Piper, Vox |

▶ Net Zero Is Stalling Out. What Now? - Editorial Board, Bloomberg |

▶ Current Share of Energy Projects Requiring High-Level Review that Are Clean Energy - Philip Rossetti, R Street |

▶ Christians shouldn’t fear AI, they should partner with it - Taylor Barkley, Fox News |

▶ China’s quest for self-reliance risks choking innovation - Yu Jie, FT Opinion |

The problem with every one of these graphs is that the focus is income and wages. We all know the wealthy do not become wealthy based on the wages they earn. The become wealthy based on interest payments and capital gains. Further, the GDP Deflator is a poor reflection of what the average American pays for the goods and services it consumes. Why did you choose to use the GDP Inflator rather than CPI?

Let's have an honest discussion about this.

“The link between productivity and worker pay is broken.” It isn’t." The author then proceeds in the next graphic to assert that it actually is, just (according his data massage) not as much as thought.

Such mendacious framing calls into question all the assertions which follows.

Poorly done.