🌎 Fear not the Anthropocene Epoch!

Time to drill, baby, drill ... for geothermal energy

Quote of the Issue

"Just as electricity transformed almost everything 100 years ago, today I actually have a hard time thinking of an industry that I don’t think AI will transform in the next several years." - Andrew Ng

The Essay

🌎 Fear not the Anthropocene Epoch!

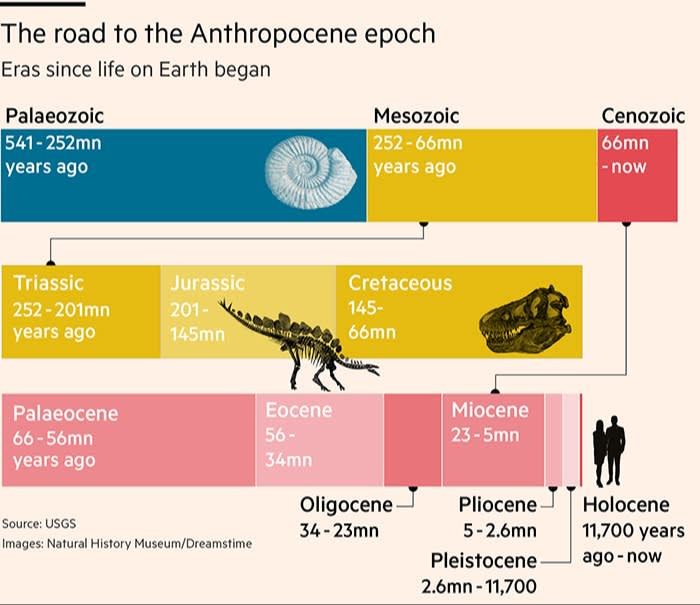

Goodbye, Holocene Epoch (from Greek, meaning “entirely new”). Welcome, Anthropocene Epoch (from Greek, meaning “human” and “new”). Probably. From a certain point of view.

According to a panel of earth scientists from around the world, humanity in the 1950s seems likely to have entered a new geological era. Now look, the Holocene had a good run, a stretch of nearly 12,000 years since the last major ice age. But human activity has likely brought that lengthy period — one of climate stability — to an end, explain the smarties of the Anthropocene Working Group:

The ‘Anthropocene’ is a term widely used since its coining by Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer in 2000 to denote the present geological time interval, in which many conditions and processes on Earth are profoundly altered by human impact. This impact has intensified significantly since the onset of industrialization, taking us out of the Earth System state typical of the Holocene Epoch that post-dates the last glaciation. … Phenomena associated with the Anthropocene include: an order-of-magnitude increase in erosion and sediment transport associated with urbanization and agriculture; marked and abrupt anthropogenic perturbations of the cycles of elements such as carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and various metals together with new chemical compounds; environmental changes generated by these perturbations, including global warming, sea-level rise, ocean acidification and spreading oceanic ‘dead zones’; rapid changes in the biosphere both on land and in the sea, as a result of habitat loss, predation, explosion of domestic animal populations and species invasions; and the proliferation and global dispersion of many new ‘minerals’ and ‘rocks’ including concrete, fly ash and plastics, and the myriad ‘technofossils’ produced from these and other materials.

That’s quite a list of human-caused harms. This entire framing is meant to suggest the new Anthropocene Epoch — still a somewhat controversial topic among geologists — represents something detrimental having happened to the Earth, with you and me at fault. (The symbolic start of this new ecological era is a small Canadian lake with plutonium markers in its rocks. The start of nuclear testing is what makes the 1950s the key Anthropocene decade.)

Indeed, the members of the AWG have made it clear that “declaring the Anthropocene could spur political action to limit humanity’s impact on the Earth,” notes the Financial Times.

An NPR piece on the identification of the lake offers this quote from one panel member: "If you know your Greek tragedies you know power, hubris, and tragedy go hand in hand. If we don't address the harmful aspects of human activities, most obviously disruptive climate change, we are headed for tragedy."

Certainly one way to interpret the macro-message here is that humanity should consume less, use fewer resources, and have less of a presence on this planet. Humanity should retreat in all ways possible.

Digging for energy

But that’s not the message of this newsletter. If we want a healthier and more prosperous humanity living on a healthier planet, then humanity must advance. I wonder what the AWG geologists would think about this important bit of geological news that broke yesterday (via Bloomberg):

In a landmark step for enhanced geothermal technology’s potential as a dependable carbon-free energy source, startup Fervo Energy has completed a performance demonstration of its commercial pilot. The Houston-based company wrapped up a full-scale, 30-day well test at its Project Red site in northern Nevada, which was able to generate 3.5 megawatts of electricity, according to a company statement. (One megawatt can power roughly 750 homes at once.) Project Red will connect to the grid later this year and power Google's data centers and infrastructure throughout Nevada.

Fervo’s “enhanced geothermal system” involves drilling deep wells, and then using fracking techniques developed by the oil and gas industry, it fractures hot, impermeable rock underground, creating an artificial geothermal reservoir. The company then pumps water into that reservoir, the water gets really hot, and then the water is pumped back to the surface to power a turbine and generate electricity. What this all adds up to is the prospect of clean, limitless, reliable energy.

Fervo cites a 2016 National Renewable Energy Laboratory study that determined there’s enough geothermal energy within a subsurface depth of five kilometers to fully satisfy U.S. electrical demands, and enough energy potential within a subsurface depth of seven kiometers to meet U.S. electrical demands five times over. The sun beneath our feet.

As Fervo CEO Tim Latimer tweeted, “We could not be more thrilled to announce these results. We are already at work on our next projects, orders of magnitude larger than our pilot. More to come on that soon. Cost-effective, clean, firm, reliable geothermal is at our fingertips, and we’re ready to rock and roll.”

Of course, that’s the spin you might expect to hear from the founder of a promising startup. So here’s what geothermal expert Wilson Ricks from Princeton University — he also cowrote a paper on the role of geothermal energy in future decarbonized energy systems — says of Fervo’s technical milestone, according to CNBC:

This is a very significant milestone in enhanced geothermal systems development. It is the first application of the advanced drilling and well stimulation techniques developed in the shale oil and gas boom to geothermal, and has demonstrated that these can be used to create artificial geothermal reservoirs delivering high flow rates. There is still more development to be done on the path to large-scale and cost-competitive commercial systems, but the significance of this achievement shouldn’t be understated. [The kind of enhanced geothermal energy systems, like those that Fervo is developing] “could do double-duty as a form of long-duration energy storage, enhancing their ability to complement wind and solar in a decarbonized grid.

Moving forward, one innovation at a time

By the way, Fervo’s Latimer pops up in a great new Wired piece on geothermal energy, “A Vast Untapped Green Energy Source Is Hiding Beneath Your Feet,” in which he comments on the company’s recent advance:

“We’ve shown that it works,” Latimer says. Now the question is how quickly can we bring it down the cost curve.” That includes getting hotter. Fervo’s Nevada wells peaked at 370 degrees Fahrenheit (190 degrees Celsius)—hotter, he points out, than any other horizontal oil and gas well in the US—and hot enough to prove that its own tools can go a bit hotter next time. There are also crucial questions about drilling, he adds: the optimal distance between the wells, the angles, the depth. “It’s not like software where you can iterate quickly,” he says. The industry needs more experiments, more projects, to figure out the most productive combination—each of them bound to be expensive and difficult.

The Wired article also tells the story of the $220 million, US Department of Enegy-funded Frontier Observatory for Research in Geothermal Energy, which is trying to accelerate breakthroughs in ESG technology and help “de-risk” geothermal for private sector investment.

Coast-to-coast ESG power plants — along with perhaps more nuclear plants and solar sites — certainly would mean continuing to leave a sizable footprint on the Earth. I mean, that’s what we do in the Anthropocene Epoch. But by leaving a footprint, we also use technology to help solve a problem created by previous technology: fossil fuel-powered industrialization. As Northwestern University economic historian Joel Mokyr has put it, “Whenever a technological solution is found for some human need, it creates a new problem. … The new technique then needs a further ‘technological fix’, but that one, in turn, creates another problem, and so on.”

Meanwhile, humanity become healthier, richer, and better able to deal with big problems. This is also known as progress. See, the Anthropocene Epoch might turn out better than many think because of human activity, not despite it.

Micro Reads

▶ Meta Unveils a More Powerful A.I. and Isn’t Fretting Over Who Uses It - Mike isaac and Cade Metz, NYT |

▶ ‘Training My Replacement’: Inside a Call Center Worker’s Battle With A.I. - Emma Goldberg, NYT |

▶ Why computer-made data is being used to train AI models - Madhumita Murgia Wired |

▶ What's standing in the way of the flying car? - Adrienne Bernhard, BBC |

▶ China’s Tech Overseer Promises to Back AI Computing Push - Debby Wu, Bloomberg |

▶ No, NEPA really is a problem for clean energy - Aidan Mackenzie and Santi Ruiz, Noahpinion |

▶ Where Did Our Belief in Abundance Come From? - Johan Norberg, Discourse |

▶ Embedded Generative AI Will Power Game Characters - Matthew S. Smith, IEEE Spectrum |

▶ China notes, July ’23: on technological momentum - Dan Wang |

▶ The Future Is Nuclear Engineers - Charlyne Smith, The Breakthrough Institute |