🚀 Faster, Please! Week in Review #43

Silicon Valley Bank, machine learning, anti-tech regulation, and the Long Boom

My free and paid Faster, Please! subscribers: Welcome to Week in Review+. No paywall! Thank you all for your support! For my free subscribers, please become a paying subscriber today. (Expense a corporate subscription perhaps?)

Melior Mundus

In This Issue

Essay Highlights:

— Blowing up the American tech sector would be bad

— If AI can help us make better decisions, that's a gamechanger

Essay Highlights

💣 Blowing up the American tech sector would be bad

The downside of Washington fully guaranteeing all those deposits in the failed Silicon Valley Bank (and Signature Bank in New York) is one of moral hazard: The federal government’s moves may encourage more reckless behavior in the future if bankers think Uncle Sam will always race to the rescue. But there are other factors also worth considering. It’s my hope and my belief that we are now in an inventive and transformative time with key advances in biology, energy, space, and artificial intelligence. And Silicon Valley is the beating heart of that civilizational push forward. Consider this, from economist Larry Summers: “It will certainly have consequences for Silicon Valley and for the economy of the venture sector which has been dynamic, unless the government assures the situation is worked through. ... the consequences really will be quite severe for our innovation system [if SBV account holders can't make payroll].” We don’t need another financial crisis, especially one where Silicon Valley is ground zero.

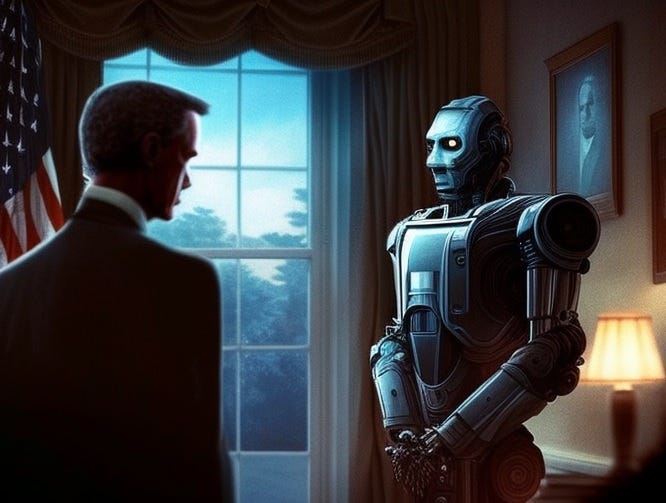

🤖 If AI can help us make better decisions, that's a gamechanger.

“A human player has comprehensively defeated a top-ranked AI system at the board game Go, in a surprise reversal of the 2016 computer victory that was seen as a milestone in the rise of artificial intelligence,” reports the Financial Times. This surprise victory for sentient life raises questions like how might superhuman intelligence affect our decision-making? And what would be the exact mechanism? To find some answers, a team of researchers from City University of Hong Kong, Yale School of Management, and Princeton University had a “superhuman AI” assess the quality of nearly 6 million professional Go moves over 71 years (1950-2021). They then created 58 billion different game patterns based on that analysis and examined how the win rates of the real human moves differed from those of the possible AI moves. Their finding: “Because AI can identify optimal decisions free of human biases (especially when it is trained via self-play), it can ultimately unearth superior solutions previously neglected by human decision-makers who may be focused on familiar solutions. … The discovery of such superior solutions creates opportunities for humans to learn and innovate further.”

⚡ Regulation versus emerging energy technology

Last week, Georgia Power said that the nuclear fission process has begun inside the Unit 3 reactor at the Vogtle nuclear plant, about 150 miles east of Atlanta. Vogtle Unit 3, once fully operational, will be the first reactor that started with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and moved all the way to completion. So given that track record, it’s perhaps unsurprising that the supposed future of nuclear fission power is taking longer than expected. They promised us small modular reactors, or SMRs, and all we’ve gotten is continually stretched-out timelines. The regulatory approval process for NuScale’s SMR began in 2008 and final approval for a tweaked reactor design may take until 2025. Here’s a fun fact: “In 2020, when it received a design approval for its reactor, the company said the regulatory process had cost half a billion dollars, and that it had provided about 2 million pages of supporting documents to the NRC,” reports MIT Tech Review. Who could conclude this process is optimal other than diehard nuclear opponents? We know what the problem is. When will we do something about it?

💥 The Long Boom that wasn't — and what we can learn

One of the best sources for late 20th-century futurist forecasts is the archives of Wired magazine. One of my all-time favorite pieces is a 1997 essay by Peter Schwartz and Peter Leyden, “The Long Boom: A History of the Future, 1980–2020.” Some things they got correct, such as Rising China, the sharp decline of global poverty, and the pervasive power of the internet. Other things, less so. Today, we’re not all driving around in hydrogen-powered cars or watching humanity walk on Mars. Broadly, the rapid productivity and economic growth of the late 1990s didn’t continue into the 21st century as they and many others of that time predicted. Perhaps more interesting is how Schwartz and Leyden looked that what might possibly go wrong with the bullish scenario, what they call “scenario spoilers” that could “cut short the Long Boom.” One lesson has to be that innovation can make a hash of our forecasts, either by unexpectedly solving/mitigating some problem, as with the Shale Revolution, or taking longer than expected to have an impact. Another lesson: liberalization doesn’t always go in one direction, though that may have seemed the case in the late 1990s. Finally, it’s always worth being on guard for the emergence of an anti-tech backlash and the revocation of social license.