💣 Environmentalism and the Unabomber

Also: 5 Quick Questions for … AI policy analyst Adam Thierer

Quote of the Issue

“The mystery of mysteries is to view machines making machines, a spectacle that fills the mind with curious and even awful speculation." - Benjamin Disraeli

The Essay

💣 Environmentalism and the Unabomber

The death of mad bomber and eco-terrorist Theodore Kaczynski doesn’t require a serious examination of his views about modern industrial society, much less a scholarly exegesis of his 35,000-word manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future. As political scientist and AEI scholar James Q. Wilson wrote in a January 1998 New York Times op-ed, “Apart from his call for an (unspecified) revolution, his paper resembles something that a very good graduate student might have written based on his own reading rather than the course assignments.”

If so, why not instead study the primary sources of Kaczynski’s anti-modern, anti-technology ideology? It’s not a particularly original one. The notion that the “Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race” — the first sentence of the manifesto — was being propagated by environmentalist extremists long before the essay’s 1995 publication by The Washington Post.

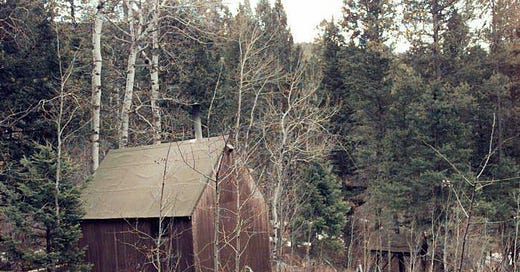

Indeed, charging what Kaczynski calls the “industrial-technological system” with creating a societal sense of alienation, dehumanization, and emotional distress, along with destroying the environment, was commonly discussed even before Kaczynski headed into the Montana wilderness in 1971. A year earlier, “sociologist of the future” Alvin Toffler had a best-seller with Future Shock, which warned about global disorientation as advanced civilization transformed into a “super-industrial society”:

In the three short decades between now and the twenty-first century, millions of ordinary, psychologically normal people will face an abrupt collision with the future. Citizens of the world's richest and most technologically advanced nations, many of them will find it increasingly painful to keep up with the incessant demand for change that characterizes our time. For them, the future will have arrived too soon.

But whereas Toffler was an optimist about humanity’s ability to adapt and prosper amid rapid change, Kaczynski wanted to "decentralize society" and "reduce the complexity of technology.” Everyone back to the wilderness. Again, nothing new here.

By the early 1970s, such views were at the core of the environmental movement. In particular, Kaczynski was known to be influenced by the writings of French philosopher Jacques Ellul, who wrote about the socioeconomic system that drove our technological imperative, a governmental-industrial-university entity that fellow technology critic Lewis Munford called the “megamachine.” As historian Thomas P. Hughes writes in “American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm, 1870-1970,”:

Ellul suggested that we, like Esau, are selling our birthright for a mess of pottage, that the price we pay for a cornucopia of goods and services is slavery. We fail to see that, as technology solves problems, it also creates them, as in the case of automobiles, congestion, and pollution. Furthermore, we cannot choose good technology and reject bad, for these qualities are inseparably intermixed within technological systems. He also lamented our enthusiasm for technology. Sputniks, he wrote, “scarcely merit enthusiastic delirium,” and “it is a matter of no real importance whether man succeeds in reaching the moon, or curing disease with antibiotics, or upping steel production. The search for truth and freedom are the higher goals. . . . “ Ellul was not referring to political freedom but to freedom from the deterministic forces of technology, especially those stemming from the momentum of large technological systems of production, communication, and transportation.

Kaczynski echoes Ellul throughout his manifesto: “There has been a consistent tendency, going back at least to the Industrial Revolution for technology to strengthen the system at a high cost in individual freedom and local autonomy. Hence any change designed to protect freedom from technology would be contrary to a fundamental trend in the development of our society.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faster, Please! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.