💣 Environmentalism and the Unabomber

Also: 5 Quick Questions for … AI policy analyst Adam Thierer

⭐ First things first, I have a great offer for all my free subscribers: a full-year subscription for just $1 a month. That works out to a whopping 80 percent discount from the usual $60 a year. That’s right, just a buck a month for the next 12 months, or $12 for 12 months. This offer won’t last long!

It’s going to be a fascinating time as emerging technologies such as generative AI continue to emerge amid a year sure to be full of surprises, both economic and political. What’s going to happen next? Let’s find out together as we work to create a better world.

Melior Mundus

The Essay

💣 Environmentalism and the Unabomber

The death of mad bomber and eco-terrorist Theodore Kaczynski doesn’t require a serious examination of his views about modern industrial society, much less a scholarly exegesis of his 35,000-word manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future. As political scientist and AEI scholar James Q. Wilson wrote in a January 1998 New York Times op-ed, “Apart from his call for an (unspecified) revolution, his paper resembles something that a very good graduate student might have written based on his own reading rather than the course assignments.”

If so, why not instead study the primary sources of Kaczynski’s anti-modern, anti-technology ideology? It’s not a particularly original one. The notion that the “Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race” — the first sentence of the manifesto — was being propagated by environmentalist extremists long before the essay’s 1995 publication by The Washington Post.

Indeed, charging what Kaczynski calls the “industrial-technological system” with creating a societal sense of alienation, dehumanization, and emotional distress, along with destroying the environment, was commonly discussed even before Kaczynski headed into the Montana wilderness in 1971. A year earlier, “sociologist of the future” Alvin Toffler had a best-seller with Future Shock, which warned about global disorientation as advanced civilization transformed into a “super-industrial society”:

In the three short decades between now and the twenty-first century, millions of ordinary, psychologically normal people will face an abrupt collision with the future. Citizens of the world's richest and most technologically advanced nations, many of them will find it increasingly painful to keep up with the incessant demand for change that characterizes our time. For them, the future will have arrived too soon.

But whereas Toffler was an optimist about humanity’s ability to adapt and prosper amid rapid change, Kaczynski wanted to "decentralize society" and "reduce the complexity of technology.” Everyone back to the wilderness. Again, nothing new here.

By the early 1970s, such views were at the core of the environmental movement. In particular, Kaczynski was known to be influenced by the writings of French philosopher Jacques Ellul, who wrote about the socioeconomic system that drove our technological imperative, a governmental-industrial-university entity that fellow technology critic Lewis Munford called the “megamachine.” As historian Thomas P. Hughes writes in “American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm, 1870-1970,”:

Ellul suggested that we, like Esau, are selling our birthright for a mess of pottage, that the price we pay for a cornucopia of goods and services is slavery. We fail to see that, as technology solves problems, it also creates them, as in the case of automobiles, congestion, and pollution. Furthermore, we cannot choose good technology and reject bad, for these qualities are inseparably intermixed within technological systems. He also lamented our enthusiasm for technology. Sputniks, he wrote, “scarcely merit enthusiastic delirium,” and “it is a matter of no real importance whether man succeeds in reaching the moon, or curing disease with antibiotics, or upping steel production. The search for truth and freedom are the higher goals. . . . “ Ellul was not referring to political freedom but to freedom from the deterministic forces of technology, especially those stemming from the momentum of large technological systems of production, communication, and transportation.

Kaczynski echoes Ellul throughout his manifesto: “There has been a consistent tendency, going back at least to the Industrial Revolution for technology to strengthen the system at a high cost in individual freedom and local autonomy. Hence any change designed to protect freedom from technology would be contrary to a fundamental trend in the development of our society.”

Likewise, one can also find in Kaczynski’s views plenty of British economist E.F. Schumacher’s “small is beautiful” philosophy that advocated a rejection of megamachine-driven economic growth and increased consumption in favor of small-scale, community-based living. (The “grown local” foods movement is pure Schumacher.) Although Kaczynski attacks the political left, his views on "the system” were fully in line with the era’s counterculture thinking. Hughes:

Reflective radicals of the 1960s, both in America and abroad, attacked modern technology and the order, system, and control associated with it. The counterculture called for the organic instead of the mechanical; small and beautiful technology, not centralized systems; spontaneity instead of order; and compassion, not efficiency.

For many environmentalists and worriers about the megamachine, time stopped in the early 1970s. They never anticipated the 1960s countercultural movement ended up helping give rise to Silicon Valley and the Information Technology revolution that upended Corporate America or Washington’s retreat from the Atomic and Space Ages, both supposedly driven by Mumford’s unstoppable megamachine. And there can be little doubt that America today is more open, more free, and more tolerant than it was in 1971. It’s never been easier to express and amplify one’s opinion than right now. It’s certainly easier than ever to find the views of the descendants of the 1970s environmental alarmists, such as the degrowth movement.

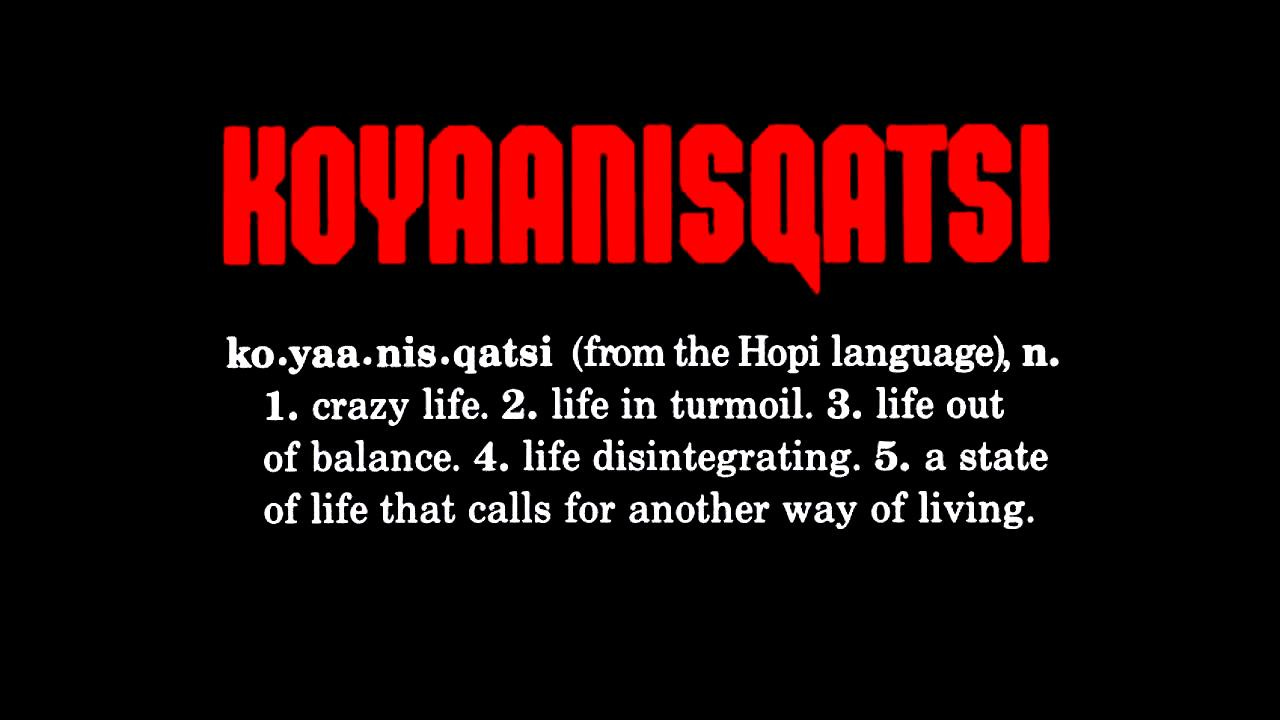

I would certainly recommend reading Ellul, Schumacher, Mumford, or Hughes rather than the murderer Kaczynski. Another option: Watch Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out of Balance the 1982 non-narrative film directed by Godfrey Reggio with music composed by Philip Glass and cinematography by Ron Fricke. Using various visual techniques such as slow and speeded-up motion, this “tone poem” juxtaposes scenes natural and artificial to suggest a world of daunting and unsustainable disequilibrium. Koyaanisqatsi begins with the ancient Great Gallery rock mural of Horseshoe Canyon in southeastern Utah and then cuts to the fiery chaos of a Saturn V launch, then followed by long, languid scenes of the Grand Canyon.

Another example: A massive parking lot of cars cuts to a line of tanks. There’s a lengthy sequence of a taxiing United Airlines 747 slowly approaching the camera across a runaway rippling with heat waves. Perhaps the most famous bits are time-lapse shots of humanity merely going about its business, such as shots from high above busy freeways and Times Square.

For me, Koyaanisqatsi doesn’t have the intended effect. The Boeing 747 and Saturn V were, in their own way, are as beautiful as the rock murals and natural wonders such as the Grand Canyon, clouds, and oceans. While the film treats hustling pedestrians as ants overwhelming nature, I think it misses a different kind of beauty. Film critic Roger Ebert put it well:

All of the images in this movie are beautiful, even the images of man despoiling the environment. The first shot of smokestacks is no doubt supposed to make us recoil in horror, but actually I thought they looked rather noble. The shots of the expressways are also two-edged. Given the clue in the title, we can consider them as an example of life out of control. Or — and here's the catch — we can marvel at the fast-action photography and reflect about all those people moving so quickly to their thousands of individual destinations. What a piece of work is a man! And what expressways he builds!

"Koyaanisqatsi," then, is an invitation to knee-jerk environmentalism of the most sentimental kind. It is all images and music. There is no overt message except the obvious one (the Grand Canyon is prettier than Manhattan). It has been hailed as a vast and sorrowful vision, but to what end? If the people in all those cars on all those expressways are indeed living crazy lives, their problem is not the expressway (which is all that makes life in L.A. manageable) but perhaps social facts such as unemployment, crime, racism, drug abuse and illiteracy -- issues so complicated that a return to nature seems like an elitist joke at their expense.

Lots of old-school, scarcity-obsessed environmentalists, even ones barely twenty-years old such as activist Greta Thunberg, continue to miss the noble beauty of humanity’s achievements, as well as accomplishments such the big reductions in global poverty and inequality over the past generation. What they decry as a “life out of balance” is actually the creative destruction and human drive that moves civilization forward, solving old problems while creating news ones, yet forward, ever forward. Faster, please!

5 Quick Questions for … AI policy analyst Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer is a resident senior fellow at the R Street Institute, where he writes about technology and innovation. Last fall, Adam offered his 5 Quick Questions thoughts on dystopian science fiction to Faster, Please! readers. In this Q&A, Adam offers his thoughts on artificial intelligence regulation — a topic he’s written much about.

1/ What are the legitimate AI concerns that should prompt legislators to act with regulation? If America's tech companies pursue AI advances unregulated and unfettered, what is the downside risk?

The current policy debate over artificial intelligence is haunted by many mythologies and mistaken assumptions. The most problematic of these is the widespread belief that AI is completely ungoverned today. As I detailed in a recent R Street Institute report, nothing could be further from the truth. Our federal government is massive—2.1 million employees, 15 cabinet agencies, 50 independent federal commissions and over 430 federal departments—and many government officials have already started considering how they might address AI and robotics.

Many agencies have broad power to regulate specific algorithmic or robotic risks that could arise in their respective areas, and they are already using that authority. Some of the most active agencies include the Federal Trade Commission, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the Federal Aviation Administration, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Consumer Product Safety Commission. The courts and our common law system are also starting to address novel AI problems as cases develop.

We can fill governance gaps as needed from that starting point. Algorithmic systems may create new challenges in some contexts and require additional policies to address things like predictive policing or law enforcement use of AI or robotic technologies, among other things.

2/ You recently suggested that AI regulation proposals in the senate might spell "the beginning of a 'Mother, May I?' permission slip-based regulatory regime for computational technology that will slam the brakes on AI innovation." How consequential would that brake-slamming be in terms of the costs of overregulation?

Another myth driving the artificial intelligence debate is the idea that “AI” is a single regulable thing. Artificial intelligence is probably too amorphous of a term to regulate in a holistic, singular fashion. “There is no single universally accepted definition of AI, but rather differing definitions and taxonomies,” a U.S. Government Accountability Office report has noted. That is precisely why we are seeing the expansion of context-specific policies that target concrete algorithmic risks related to specific industries and applications.

That is a more workable way of regulating compared to the proposals we are seeing today for AI governance, which are tantamount to calls for broad-based control of computing more generally. In fact, it is not an overstatement to say that a veritable war on computation could be looming. Some regulatory advocates, and even companies like Microsoft and OpenAI, are proposing to regulate the full AI production stack: applications, models, data sets, and even data centers. It would constitute comprehensive control of computation in the name of addressing future algorithmic risks. It could potentially entail government caps on the aggregate amount of compute that could be created or sold and widespread surveillance of AI research and development. Regulatory advocates suggest the new regime could take the form of a top-down licensing system that restricts output according to pre-determined thresholds established by the Department of Energy or some other new AI regulatory body.

This is why I call it a 'Mother, May I?' permission slip-based regime for compute. This regulatory scheme will lead to a highly politicized licensing process in which developers fight over who gets to do large training runs or develop powerful chips or GPU clusters. Once government makes artificial intelligence artificially scarce through such supply-side limitations, the politics of this will get really ugly and it will spawn a cesspool of rent-seeking activity. Federal compute regulation could come to resemble fights we’ve witnessed before over licensed taxicab medallions and broadcast spectrum licenses, where the biggest and most politically connected leverage their influence over the system to beat back new rivals and innovations. The consequences for advanced algorithmic innovation will be profound as many important applications and services never get a chance to get off the ground.

3/ You noted that the recent AI oversight hearing in the Senate featured "references to the atom bomb and various dystopian scenarios." Is dark and gloomy sci-fi infecting our political debates?

As we discussed last time we chatted, depictions of AI and robots in sci-fi and pop culture tend to be highly dystopian. It’s hard to identify many books, shows, or movies today that offer a positive depiction of advanced technology, and especially AI. The robots are either going to eat us, enslave us, or lead to our destruction in some fashion.

All that misery has rubbed off on the public and politicians and shaped their thinking about AI and robotics. As you perfectly summarized here recently, “A big reason why opinion polls suggest considerable concern about recent AI advances is that our culture has produced few visions of a positive future with supersmart computers.” I do not see this problem getting any better, unfortunately. Every writer on strike in Hollywood currently is already terrified about AI taking their jobs. What do you think their next script is going to look like once they go back to work!

4/ Do our legislators in Congress and their staff understand AI enough to begin thinking about how to regulate it? If not, what misconceptions are prevalent?

A recent New York Times article probably put it best when noting, “As A.I. Booms, Lawmakers Struggle to Understand the Technology.” However, as I argued in a study for AEI last year about the current state of tech policymaking efforts, Congress isn’t full of ignorant people, it’s just full of extremely busy people trying their best to keep tabs on very fast-moving technology. Some of them can and have taken the time to get up to speed on the issues, but they are increasingly overwhelmed by the world of combinatorial innovation we now live in.

Essentially, mini-technological revolutions keep happening one after another, usually building on the power of previous ones. I have likened this situation to a series of waves that come flowing in to shore faster and faster. “As soon as one wave crests and then crashes down, another one comes right after it and soaks you again before you’ve had time to recover from the daze of the previous ones hitting you.” AI and the computational revolution now push this techno-supersoaking into hyperdrive, making it even more difficult to get sensible policies enacted that won’t be obsolete a short time later. This opens up the danger of rash regulatory decisions based on misperceptions or bogus fears, some of which are being fueled by the technopanic mentality surrounding AI at the moment.

5/ Do America's politicians have any understanding of the possible benefits of AI and the scale of those benefits, from boosting economic growth to geopolitical advantages?

While some politicians make passing reference to the importance of AI for economic growth and geopolitical standing, they usually move along quickly to recite a litany of grievances they fear far more. Politicians and pundits fearing the future is nothing new, but Chicken Little-ism has now been kicked into overdrive. Consider the Biden administration’s recent “Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights,” which opens with an airing of grievances about how algorithmic systems are “unsafe, ineffective, or biased”; “deeply harmful”; “threaten the rights of the American public”; and “are used to limit our opportunities and prevent our access to critical resources or services.” Those are just the first few lines of the document!

This and other Biden administration statements mostly stress worst-case scenarios about AI. The problem is, as I argued in my book on Permissionless Innovation, “living in constant fear of worst-case scenarios—and premising public policy on them—means that best-case scenarios will never come about.” We have somehow forgotten that the greatest of all AI risks is shutting down AI altogether.

At some point, such negative thinking influences our nation’s innovation culture and begins to discourage entrepreneurs and investors from putting their creative energy and money into AI and robotics. Worse yet, because we live in a world where global innovation arbitrage is a reality, many innovators and investors may move to wherever they are treated more hospitably.

6/ OpenAI CEO Sam Altman suggests heavier regulation for dominant AI players and lighter regulation for smaller companies. Is that a good idea?

It’s always easy for market leaders to call for preemptive regulation of their field. Firms like OpenAI and Microsoft have two big advantages in doing so. Their first-mover advantage with large-scale AI systems means they already have a leg up on other current or future competitors. Second, more established firms tend to have a political infrastructure—lobbyists, consultants, compliance officers, etc.—in place to handle the compliance costs associated with all the resulting red tape. For larger firms, regulation is often treated as just another cost of doing business, and they implicitly understand it will raise rivals’ costs.

To his credit, OpenAI’s Altman recognizes that this is a problem for future innovation, but the regulatory regime that he and Microsoft have sketched out could ensnare smaller competitors or open source efforts anyway because they want it to cover “powerful” AI models or “advanced” supercomputing systems. Thus, even if newer players could get the venture capital and other resources needed to get a major effort off the ground, they would likely be hit immediately with the technocratic mandates that OpenAI and Microsoft favor. This is probably what led The Economist magazine to conclude that, “tech giants want to strangle AI with red tape” because, “[t]hey want to hold back open-source competitors.” Even if that is not their express intent, it could be the result anyway.

7/ Enthusiasm for regulating AI and "reining in" Big Tech seems to be bipartisan. Are Republicans and Democrats, broadly speaking, approaching this issue differently or are they essentially of one mind?

The culture warriors on the political left and right all want government to exert more control over algorithmic systems, but they have completely different rationales in doing so. As I recently told Politico, "[t]he left will say AI is hopelessly biased and discriminatory; the right will claim AI is just another ‘woke’ anti-conservative conspiracy.” It’s hard to know how this drama plays out, therefore. If a new AI regulatory agency was created and given broad-based powers to enforce “algorithmic transparency” or address “AI bias,” we can imagine that new body being tugged in radically different directions whenever a new administration took over. And congressional lawmakers would endlessly jawbone that agency to do their bidding.

Consider the clownish behavior we’ve witnessed at many recent congressional hearings about social media regulation, in which tech CEOs are brought in for a good public flogging before the cameras so that politicians can play to their respective bases. Now, imagine those same hearings including five bureaucrats from a new Federal AI Commission, who were subjected to the same sort of brow-beating by their congressional appropriators who tell them: “Clean up this mess, or else.” We’re looking at the mass politicization of artificial intelligence.

Micro Reads

Will generative AI boost productivity? - Editorial Board, FT | Just how high generative AI can rise up the curve, once — and indeed if — it clears the dip, depends on its usefulness. It may boost productivity in knowledge-based jobs, speeding-up doctors’ diagnoses and legal contract-writing, but some service sectors may be less affected. By accelerating the research process itself, it could drive tech progress and iterative productivity gains. Complementary changes are important too. Railways eventually raised efficiency, but that is because industry and trade were also booming. If governments adopt AI, to slash form-filling for example, that would reduce other brakes on productivity.

Robot gardener grows plants as well as humans do but uses less water - Alex Wilkins, New Scientist |

OpenAI CEO Calls for Collaboration With China to Counter AI Risks - Karen Hao, WSJ |

Artificial brains are helping scientists study the real thing - The Economist |

Silicon Valley Confronts the Idea That the ‘Singularity’ Is Here - David Streitfeld, NYT | The Singularity’s intellectual roots go back to John von Neumann, a pioneering computer scientist who in the 1950s talked about how “the ever-accelerating progress of technology” would yield “some essential singularity in the history of the race.” Irving John Good, a British mathematician who helped decode the German Enigma device at Bletchley Park during World War II, was also an influential proponent. “The survival of man depends on the early construction of an ultra-intelligent machine,” he wrote in 1964. The director Stanley Kubrick consulted Mr. Good on HAL, the benign-turned-malevolent computer in “2001: A Space Odyssey” — an early example of the porous borders between computer science and science fiction.