☄ 'Don’t Look Up' suffers from a misguided dystopian gloom

Also: water on Mars, 2022 unemployment; technological diffusion; and more . . .

“Trying to rely on the sheer good luck of avoiding bad outcomes indefinitely would simply guarantee that we would eventually fail without the means of recovering.” - David Deutsch, The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

🎄 Note to my wonderful Faster, Please! subscribers: This newsletter will be modified, both in format and publishing schedule, between now and year end. Have a wonderful holiday season! And please tell your family, friends, and colleagues — even randos on the street — to check out Faster, Please and subscribe!

Short Read

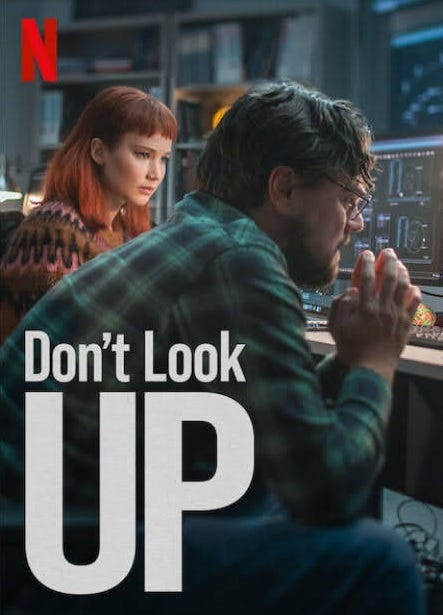

☄ The dystopian gloom of ‘Don’t Look Up’ is misguided

Don’t Look Up, now streaming on Netflix, is a black comedy about a pair of astronomers (Jennifer Lawrence and Leonardo DiCaprio) struggling to warn the world about an approaching killer comet. Apparently the whole thing is an allegory about climate change and the futility of expert persuasion in the age of social media, “fake news,” and late capitalism. The Rotten Tomatoes “critics consensus” is that the film “aims too high for its scattershot barbs to consistently land, but Adam McKay's star-studded satire hits its target of collective denial square on.”

Of course, one can question whether climate change is an extinction-level event like a ginormous comet or asteroid — as it’s frequently portrayed by activists and popular entertainment — while accepting the very real dangers involved for humanity. (Indeed, perhaps overstating risk is a poor long-term communications strategy.)

Just how dangerous is climate change? In The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity (published in March 2020 as we all became fully aware of dangers from the spreading COVID-19 pandemic) Toby Ord, a senior research fellow at the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University, outlines the existential danger from various threats. Among them: nuclear war, climate change, engineered pandemics, and AI. This is key: Ord isn’t just evaluating the risk of human extinction, but also the risk of a permanent, “no-way-back” loss of all the potential prosperous futures for humanity.

Consider a world in ruins: an immense catastrophe has triggered a global collapse of civilization, reducing humanity to a pre-agricultural state. During this catastrophe, the Earth’s environment was damaged so severely that it has become impossible for the survivors to ever re-establish civilization. Even if such a catastrophe did not cause our extinction, it would have a similar effect on our future. The vast realm of futures currently open to us would have collapsed to a narrow range of meager options.

Regarding climate change, Ord spends considerable time running through potential destructive impacts such as “reduced agricultural yields, sea level rises, water scarcity, increased tropical diseases, ocean acidification and the collapse of the Gulf Stream.” Yet, he adds, “none of these threaten extinction or irrevocable collapse.” For example: A “runaway greenhouse effect” scenario where emission-driven warming increases until the oceans boil and all complex life goes extinct is unsupported by current research. Burning fossil fuels isn’t going to turn Earth into Venus.

But what about a severe warming that makes Earth just too hot for humans, even if the oceans don’t boil away. Ord:

[The] most important known effect of climate change from the perspective of direct existential risk is probably the most obvious: heat stress. We need an environment cooler than our body temperature to be able to rid ourselves of waste heat and stay alive. More precisely, we need to be able to lose heat by sweating, which depends on the humidity as well as the temperature. A landmark paper by Steven Sherwood and Matthew Huber showed that with sufficient warming there would be parts of the world whose temperature and humidity combine to exceed the level where humans could survive without air conditioning. With 12°C of warming, a very large land area — where more than half of all people currently live and where much of our food is grown — would exceed this level at some point during a typical year. Sherwood and Huber suggest that such areas would be uninhabitable. This may not quite be true (particularly if air conditioning is possible during the hottest months), but their habitability is at least in question. However, substantial regions would also remain below this threshold. Even with an extreme 20°C of warming there would be many coastal areas (and some elevated regions) that would have no days above the temperature/ humidity threshold. So there would remain large areas in which humanity and civilization could continue.

To be clear, such a scenario would be, as Ord rightly adds, “an unparalleled human and environmental tragedy, forcing mass migration and perhaps starvation too.” Considerable resources should be invested to preventing it or even reversing it through geoengineering. Wealth creation and technological progress are key to humanity’s resilience and survival.

And not just from a changing climate. It’s ironic that Don’t Look Up chose a giant space rock as its existential threat given that humanity is already taking this risk pretty seriously. Just last month, NASA launched the Double Asteroid Redirection Test mission on a SpaceX Falcon 9. The probe is meant to smash into a small asteroid next fall as practice for deflecting such near-earth objects in the future. Between funding both deflection and monitoring efforts, “no other existential risk is as well handled as that of asteroids and comets,” Ord concludes. And that’s especially true, perhaps, given all the cognitive quirks hampering our ability to do long-term risk assessment. (An essay for another issue.)

Let me conclude with this bit of a chat I had with Ord last summer:

Pethokoukis: I wonder if people don’t focus on these risks because they just don’t see what we have to lose. There’s so much negativity in popular media about the future, so we just don’t have an optimistic image of the future that makes them think we have the chance for something pretty spectacular. So what is that great image of the future that’s at risk, which should motivate us to overcome these risks?

Ord: I think that if you look at the past and you see this accumulation of innovations over the hundred billion humans that have come before us and everything that they built up around us, it’s no surprise that our lives are of higher quality than lives in the past because we have a hundred billion people who worked together to build this for us. And if you look in more detail at the statistics, lifespans have more than doubled over the last 200 years. The country with the lowest life span now is higher than the country with the highest lifespan was 200 years ago.

So we’ve had massive improvements in prosperity, and in things like literacy and a lot of areas that really matter. And if you look at the history of pessimism on this, at this kind of continuous progress at some kind of scale — if you zoom out enough, let’s say every 50 years getting substantially better than 50 years before, even though there could well be serious downturns for particular areas — it’s very hard to understand why, seeing all of this improvement behind us, you’d predict that we’re at the peak now and it’s going to get worse. So that’s one reason just to kind of see this continuing quest for a more just and prosperous and free society.

But also you could look back and ask, “What have we got to lose?” As well as losing the future, we would lose everything from the past. We would be the first generation out of thousands, 10,000 generations, to break this chain. And if you think about what’s bad if a culture is destroyed, everything about that would be even worse. In this case, it would be the final ruin of every language, culture, and tradition. Every temple and cathedral all destroyed forever. And ultimately, the force in the universe that was pushing towards what is good or just, in terms of moral action — the fact that humans, unlike chimpanzees or birds, can actually see that something would be better for others or it would be just, and that’s a reason to do it and to push in that direction — that would be gone. As well as love and appreciation of beauty — all of these things would be forever stripped from the world.

So I think we’ve got a lot to lose. I can understand why people in a moment of despair kind of throw up their hands and say these kinds of things, but I think if they really reflect on it, we have everything to lose.

Micro Reads

🌌 Large deposits of water found on Mars below the surface at the equator - New Scientist | “A region of the Valles Marineris canyon system on Mars, one of the biggest in the solar system, appears to contain large amounts of water locked just beneath the surface, making it potentially useful for future astronauts.”

📈 10 Questions for 2022 - Goldman Sachs | I’ll highlight question #4: “Will the unemployment rate fall below its 2019 average of 3.7%?” From the report:

Yes. We took our unemployment rate forecast far below consensus at the start of this year after the Democrats’ win in the Georgia Senate elections made a large fiscal package likely. We stuck with our forecast when the initial post-vaccination pace of labor market recovery proved disappointing, because we thought that strong labor demand would eventually produce large job gains and suspected that enhanced unemployment benefits were temporarily delaying the return to work. We later proved that this indeed was the case by comparing workers in states in which benefits expired early with those in states where they expired late, a finding that an academic study has since replicated. Steady labor market progress should continue in 2022. We expect the unemployment rate to fall from 4.2% now to 3.9% by February, the last report before the March FOMC meeting, and to 3.5% — the pre-pandemic 50-year low, and the lowest of the FOMC’s NAIRU estimates — by end-2022

☎ Organizational Frictions and Increasing Returns to Automation: Lessons from AT&T in the Twentieth Century - James J. Feigenbaum & Daniel P. Gross, NBER | Devising an innovation is not the same thing as implementing an innovation throughout an economy, or even throughout a single company. The classic example of this phenomenon is the slow march of the electric dynamo. Here’s another:

AT&T was the largest U.S. firm for most of the 20th century. Telephone operators once comprised over 50% of its workforce, but in the late 1910s it initiated a decades-long process of automating telephone operation with mechanical call switching — a technology first invented in the 1880s. We study what drove AT&T to do so, and why it took one firm nearly a century to automate this one basic function. Interdependencies between operators and nearly every other part of the business were obstacles: the manual switchboard was the fulcrum of a complex system which had developed around it, and automation only began after the firm and automatic technology were adapted to work together. Even then, automatic switching was only profitable for AT&T in larger markets — hence diffusion expanded as costs declined and service areas grew.

♾ The Metaverse Is Already Here - Andy Kessler, WSJ | Over the past several decades, social platforms and video games have advanced considerably — along with their economies. Now Facebook is looking to pioneer the next generation social platform in virtual reality with its metaverse project: “Eventually, will we see virtual artwork and nonfungible tokens hanging on infinitely expandable walls? . . . Maybe, but I guarantee that the metaverse, like all new technology, will be far different from whatever we can dream up today.”

👽 What if the truth isn’t out there? - Dylan Matthews, Vox | I’ve written a bit about the potential economic impact of alien contact, partially because there’s been more solid news about this subject in the past few years than in all the previous postwar decades combined. Even Washington is taking it seriously as never before, at least in a public way. But Matthews explores the other side. (He also, coincidentally, mentions the Toby Ord book from the above essay.) Matthews:

But I also worry that belief in the extraterrestrial hypothesis is a kind of wishful thinking. If it’s wrong, and a Great Filter is in our future, that suggests our species is in immense danger. It would mean there are many, perhaps millions or billions, of civilizations like ours around the universe, but that they without fail destroy themselves at some point after they reach a certain level of technological sophistication. If that happened to them, it’ll almost certainly happen to us too.

🧓 Population Aging and the US Labor Force Participation Rate - Daniel H. Cooper, Christopher L. Foote, María J. Luengo-Prado, and Giovanni P. Olivei, Boston Fed | While there has been plenty of focus on the “great resignation” and its impact on joblessness and labor force participation, don’t forget to look at demographics:

The failure of the participation rate to get closer to its level immediately before the pandemic has puzzled many analysts. In this note, we show that the current participation rate is much less puzzling if one compares it with participation in November 2017 (the last time the unemployment rate was at its current level of 4.2 percent), rather than February 2020 (immediately before the pandemic). Since November 2017, population aging has continued to exert a strong downward pull on the participation rate, so that participation is now close to what one would expect, given the current unemployment rate and the current age structure of the population.

📱 Tweet of the issue: