🍼 Confronting global population collapse: A Quick Q&A with … demographer Nick Eberstadt

'Capital and technology can increase productivity regardless of whether manpower is growing or shrinking.'

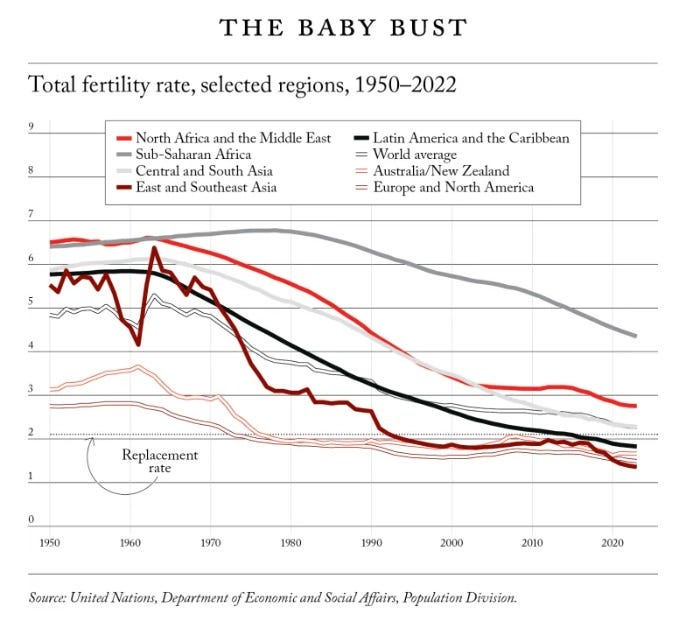

Global population will soon decline for the first time since the Black Death, but this time it's due to human choices, not disease. Falling birthrates will lead to shrinking, aging societies worldwide. Humanity is entering uncharted territory, which poses massive challenges for global governments. I asked demographer Nick Eberstadt a few quick questions about our current state of population decline and the outlook for the future.

Eberstadt is the Henry Wendt Chair in Political Economy at AEI where his research areas include demographics, economic development, poverty, and global health. He is also a senior adviser to the National Bureau of Asian Research. The most recent of his many books is Men Without Work: Post-Pandemic Edition. I urge you to check out his recent essay in Foreign Affairs, “The Age of Depopulation.” From that essay:

Net mortality—when a society experiences more deaths than births—will likewise become the new norm. Driven by an unrelenting collapse in fertility, family structures and living arrangements heretofore imagined only in science fiction novels will become commonplace, unremarkable features of everyday life.

Human beings have no collective memory of depopulation. Overall global numbers last declined about 700 years ago, in the wake of the bubonic plague that tore through much of Eurasia. In the following seven centuries, the world’s population surged almost 20-fold. And just over the past century, the human population has quadrupled.

The last global depopulation was reversed by procreative power once the Black Death ran its course. This time around, a dearth of procreative power is the cause of humanity’s dwindling numbers, a first in the history of the species. A revolutionary force drives the impending depopulation: a worldwide reduction in the desire for children.

1/ What did the population decline during the Black Death teach us about the economics of population recovery?

The demographic recovery from the Bubonic Plague in the 14th Century isn’t much of a guide for 21st Century prospects for coping with global depopulation. Humanity’s circumstances were so vastly different back then.

It is hard today to comprehend just how poor the Eurasian landmass actually was on the eve of the Black Death. To go by estimates from the Maddison Project, global per capita output might be as much as 20 times higher today. And global wealth is literally immeasurably higher now — no one has even tried to calculate that difference.

So too human capacities. Life expectancy at birth is probably over two and a half times higher today, and almost 90 percent of the world’s adults have at least some schooling nowadays, whereas 90 percent or more were illiterate back then.

Seven hundred years of advance in the frontiers of productive knowledge separates us from our Black Death era forebears; likewise 700 years of social learning in encouraging complex and fruitful economic cooperation — i.e. “business climate.”

In short, we’d be immensely better positioned today to deal with a mortality catastrophe like the one the world suffered in the 1300s. And the sort of gradual population decline that looms ahead of us now, under conditions of orderly progress and driven by low fertility, isn’t nearly in that league.

All this said, perhaps the most important thing we should remember from that last bout of global depopulation is this: Demographic disaster did not prevent the Renaissance, despite all the economic constraints and technological limits of 14th Century life.

2/ Is the declining birth rate a primarily cultural issue or an economic issue, since higher wealth correlates with fewer children across diverse societies?

Social science thinking about fertility decline betrays an abiding and unjustified bias toward what we might call “the modernization thesis.”

Received academic wisdom holds that economic development and material change are the drivers behind lower fertility levels in rich countries — and likewise the sub-replacement childbearing patterns erupting everywhere else today.

That sounds reasonable enough: Sustained fertility decline began in Europe during the Industrial Revolution, and then spread around the globe in our era of modern economic growth. But that “modernization thesis” also falls short in some pretty obvious ways.

Europe’s 18th Century decline in birth rates, after all, did not commence in England, the continent’s most modern and industrialized country. Rather it began in France — a place that was decidedly poorer, more rural, less literate and (not to put too fine a point on it) overwhelmingly Catholic as well.

Over our postwar era, development “thresholds” — income, urbanization, education — have been progressively falling for sub-replacement societies. At this writing, in fact, two of the UN’s officially designated “Least Developed Countries” are actually sub-replacement: Burma/Myanmar and Nepal. Bangladesh is on track to join this grouping, too.

The very best predictor of a population’s fertility level seems to be the number of children women say they want. (Surveys seldom pose that question to men.) So we can’t understand how many children people want unless we are willing to explore the realm of “mentality.” Social sciences can only take us so far in this.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faster, Please! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.