China's techlash explained (and lessons for America); the jobs 'robopocalypse' has been canceled; work-from-home won't jumpstart the Heartland; Futurama 1964; and more ...

“The destiny of world civilization depends upon providing a decent standard of living for all mankind” - Norman Borlaug

In This Issue:

🌐 What America should learn from China’s growing techlash

🤖 Don’t expect a jobs ‘robopocalypse’ anytime soon

🏠 Work-from-home isn’t going to jumpstart America’s heartland

🔮 The fantastic Futurama vision of tomorrow at the 1964 New York World’s Fair

🌐What America should learn from China’s growing techlash

Maybe the Chinese equivalent of “We wanted flying cars, instead we got Twitter” is “We wanted global dominance over critical technology sectors, instead we got parents scraping together cash for tuition at online tutoring firms, further discouraging them from having more kids.” Maybe something like that.

But whatever the pithy counterpart might be, the Chinese Communist Party seems unhappy with the current state of the private bits of its technology sector. In addition to new rules that basically turn those tutoring firms into nonprofits, Chinese authorities have launched regulatory crackdowns on its internet giants, Alibaba and Tencent, as well as ride-hailing service Didi Global.

One explanation: Chinese authorities would prefer more private-sector tech brainpower be devoted to sectors that Beijing more highly values — such as those specified in its “Made in China: 2025” industrial policy plan back in 2015. These include aerospace, biomedicine green-energy cars, next-generation information technology, and robotics. As Greg Ip writes in The Wall Street Journal this week: “In [President Xi Jinping’s] estimation, technology comes in two varieties: nice to have and need to have. Social media, e-commerce and other consumer internet companies are nice to have, but in his view national greatness doesn’t depend on having the world’s finest group chats or ride-sharing.”

The techlash also seems to be a matter of pure authoritarian control. The Economist writes that the CCP’s message is clear: “[T]he Marxist pursuit of power trumps market logic.” Likewise, the Financial Times editorial board concludes that this crackdown “is designed in part to demonstrate the state’s control over the economy.”

The CCP’s critique of its tech sector surely resonates with some American politicians. For example: Back in 2019, Sen. Josh Hawley, a Missouri Republican, took to the WSJ editorial page to slam Silicon Valley for creating killer apps rather than, say, curing killer diseases. Also, where are my Mars colonies? Hawley: “Men landed on the moon 50 years ago, a tremendous feat of American creativity, courage, and, not least, technology. The tech discoveries made in the space race powered innovation for decades. But I wonder, 50 years on, what the tech industry is giving America today.”

Of course, Hawley isn’t the first person made to look foolish by the unpredictability of tech-innovation life cycles. Since that op-ed, SpaceX has returned America to manned spaceflight, CRISPR gene-editing seems to hold as much promise as ever for curing disease, and just recently Alphabet’s DeepMind announced that it has used its AlphaFold artificial intelligence program to predict the shapes of nearly every protein in the human body, a breakthrough that could advance drug development and lead to a better understanding of disease. “We believe that this will represent the most significant contribution AI has made to advancing the state of scientific knowledge to date,” said DeepMind’s chief executive Demis Hassabis.

Hopefully, American policymakers will see this emerging technology renaissance as an affirmation of the American Way of Progress. That means government doing its bit: strong science investment, efficient infrastructure, regulation that doesn’t stymie entrepreneurs to innovate and build atoms rather than just bits. That also means the private sector does its part: Advancing and commercializing that science as it creates innovative goods and services that people value.

Oh, one more thing: That also means eschewing attempts to copycat China with our version of industrial policy where government selects sectors and technologies for subsidy and trade protection. Cato Institute fellow Scott Lincicome recently wrote a long analysis of the failure of American efforts at industrial policy. (We should also learn a lesson from the autonomous vehicle hype cycle.) I would also recommend a new Foreign Affairs piece by China analyst Dan Wang that highlights the shortcoming of the China Way:

If the country’s recent industrial policy programs had reached fruition, the country would be a technological giant today—but it is not. Chinese tech firms have mastered the production of certain goods, including renewable power technologies, electric vehicles, high-speed rail supplies, heavy machinery, and automotive parts. China is at the fore of 5G network deployment, boosted by Huawei’s strength in mobile networking equipment. But on bigger-ticket items that are explicit government targets, such as semiconductors and aviation technologies, China’s industrial policy has failed. … In other words, Chinese central planning has not defied economic gravity and proved that the government knows better than the market.

You can also see that failure in IMF estimates of Chinese productivity growth showing it averaged just 0.6 percent between 2012 and 2017, a sharp decline from an average of 3.5 percent over the previous five years. As my fellow AEI scholar Derek Scissors has noted, “Beijing has long abandoned the pro-market path and shows no true interest in returning to it.” Something for Washington to think about as it considers the shape of US economic policy over the next decade.

🤖 Don’t expect a jobs ‘robopocalypse’ anytime soon

One reason some economists forecast faster productivity growth over the near term is greater tech adoption by business, driven by the Covid-19 pandemic. Here are three examples from reporter Ben Casselman at The New York Times:

When Kroger customers in Cincinnati shop online these days, their groceries may be picked out not by a worker in their local supermarket but by a robot in a nearby warehouse.

Gamers at Dave & Buster’s in Dallas who want pretzel dogs can order and pay from their phones — no need to flag down a waiter.

And in the drive-through lane at Checkers near Atlanta, requests for Big Buford burgers and Mother Cruncher chicken sandwiches may be fielded not by a cashier in a headset, but by a voice-recognition algorithm.

So maybe get ready for another Automation Panic. Or perhaps a continuation of the one we saw before the pandemic. Stories about big advances in AI and robotics sparked a flurry of news reports and books warning that smart machines were going to take all the jobs. Of course, at the very time that warnings were escalating, unemployment was falling to a 50-year low, with wages rising across the board, especially at the bottom of the income scale.

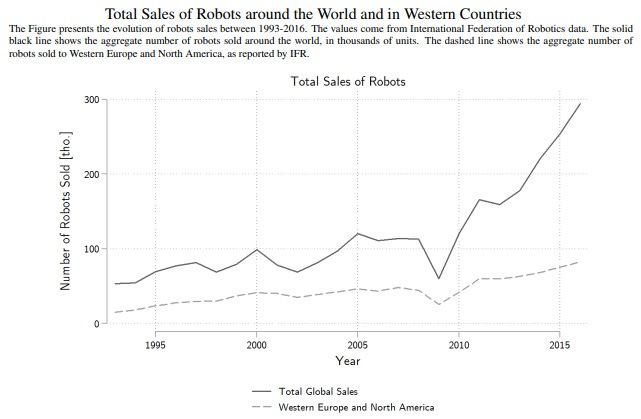

An important data point in thinking about the impact of automation on jobs going forward is the new NBER working paper “Robots and Firm Investment” by Efraim Benmelech (Northwestern University and NBER) and Michał Zator (University of Notre Dame). Using cross-country data on robotization as well as administrative data from Germany, the economists conclude that the impact of robots, specifically, on firms and labor markets has been limited:

Commenting on the disparity between measures of investment in information technology and output productivity, Robert Solow famously quipped at the beginning of the IT-driven technological revolution that “you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” More than 30 years later, another technological revolution again seems imminent – in what is now called “The Fourth Industrial revolution” a great deal of attention is devoted to automation and industrial robots. … This paper shows that despite these omnipresent predictions, today it is again hard to see robots not only in the aggregate productivity statistics, but also anywhere else. … Usage of robots is close to zero outside of manufacturing and even within manufacturing robotization is very low for all but few poster-child industries, such as automotive. … A decade after Solow’s observation the economic impact of IT was evident, but the same explosive growth pattern is not visible in robotics. … Recent increases in the absolute numbers of robots sold are driven mostly by catching-up of manufacturing in China and other developing nations rather than by increasing robotization in developed countries. … It does not appear, therefore, that we should expect a “robocalypse” in the foreseeable future.

A few other points. First, there’s no doubt that robotics, combined with other technologies, is having a significant effect on the economy and labor markets, such as hollowing out the “middle-skill” part of the labor market. Second, the impact of robotics could well change as technology advances. Third, we should want better and more robotics. While some jobs will be replaced, history suggests others will be complemented and made more productive, and new tasks will be created. And attempting to limit technological “creative destruction” is a sure path toward stagnation.

🏠Work-from-home isn’t going to jumpstart America’s heartland

As trends go, 5,000 years of urbanization qualifies as an awfully persistent trend. So to suggest “cities are over” or that American largest (and most productive) cities will soon look like the backdrops of a post-apocalyptic zombie film — well, it’s quite a bold forecast. Yet during the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic, there was plenty of musing about just such a scenario. A weak version of such a prediction is that lots of Americans would take advantage of remote work and head to the American heartland, allowing all that tech hub vitality to seep into the country’s “left behind” spaces. A silver lining of talent diffusion prompted by terrible disease.

But Heartland America better not have counted on population losses in superstar cities being their gain. It just didn’t happen. A Brookings analysis finds the gross total out-migration to the classic Heartland states and the Mountain states was only 198,000, out of 4.7 million outbound moves from the coastal metro areas of New York, Los Angeles, Washington D.C., and Seattle.

These results are in keeping with the expectations of Alain Bertaud, a senior research scholar at New York University’s Marron Institute of Urban Management. I highly recommend his 2018 book Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities. (Here also is a transcript from my early 2020 Political Economy podcast chat with Bertaud.) This is what he said at a May 2020 virtual event at AEI:

Cities have been through a lot of crises in their history. Some have been completely bombed out during the last war — for instance, cities like Berlin. During the Black Death, cities were also practically eradicated. There have been a lot of crises, and every time they come back. Now, maybe the only thing which is different this time is the ability to work at distance, using the tools we are using right now. I don’t think that this will make much of a difference frankly. … Cities are very attractive for a number of reasons — some economic, some cultural — and this is not likely to change. So I think we are a bit overreacting. After September 11, for instance, everybody was saying, “Well, this is the end of skyscrapers. You know, nobody will ever build a skyscraper anymore.” We have probably built more skyscrapers all over the world since September 11 than we had before.

🔮 The fantastic Futurama vision of tomorrow at the 1964 New York World’s Fair

In my previous Faster, Please! newsletter, I wrote about all the ways American society might promote a techno-optimist vision, including embracing World’s Fairs in a way it hasn’t since the 1960s. Back then, the expositions hosted by America, in particular, really tried to present an attractive vision of what tomorrow could be. That was certainly true of the New York City World’s Fair of 1964. The most popular attraction, next to Michelangelo’s Pieta, was the GM-sponsored Futurama ride, an update of the popular Futurama ride at the 1939 New York fair. It provided an integrated vision of all the wonders that the futurists of the era were predicting, from Moon bases to weather control to undersea mining. It was a depiction of vast, global abundance and total human dominance over nature.

The narration:

Welcome to Futurama 2! Welcome to a journey into the future — a journey for everyone today into the everywhere of tomorrow. Let us explore together the future — a future not of dreams, but of reality.

It is now tomorrow. On the moon, there is no air to breathe. No rain to fall. No sound that can be heard. Yet here is man exploring, building his first bridgehead in his span of space.

Lunar rovers float magically over powdered planes, range the craters’ edge, their elastic train-like bodies conforming to every surface character of the moon.

Here are bases of communication and supply — islands of existence built to withstand the melting heat of the lunar day, the shattering cold of the lunar night.

Men in space now monitor the Earth, while men on Earth are finding a whole new world of answers to the worldwide needs of man.

A diamond brilliance draws us to a frozen shore — to Antarctica, the southern polar cap of the world! Here, nations of the world, speaking the common language of science, probe for the Earth's secrets through countless centuries of ice. In mobile laboratories, form expeditions into the vast white wastelands of the still-unknown.

And here is Weather Central, forecasting to the world the great climatic changes born in the Antarctic’s never-ending winds. Technicians, kept warm within their walls of ice, gather data from the depths of space. From polar winds. Surrounding seas. In microseconds, relaying information wherever needed anywhere on Earth.

Three-quarters of our earth lies beneath the cold, still deeps of the sea — a water world in which we now can find abundance far beyond our dreams. Now we can farm and harvest a drifting, swimming, never-ending nourishment. Food enough to feed seven times the population of the Earth!

In aqua-copters, search the ocean floor to find miles-deep, vast fields of precious minerals and ores. And in the deepest trenches of the seas, study it firsthand: long-hidden secrets of survival. Work easily the rich oil deposits of the continental shelves while trains of submarines transport materials and goods along the waterways of the undersea.

And in warmer seas, our new realms of pleasure. A weekend, if you wish, at Hotel Atlantis, in the kingdom of the sea. A holiday of thrills and of adventure — of radiant wonders in the sun-bright gardens of the sea!

Fabulous coral reefs lead us back to the land. An equatorial land. Now technology has found a way to control the wild profusion of this wonder world.

A jungle road is built in one continuous operation. First, a searing ray of light. The laser beam cuts through the trees! Then a giant machine — a factory on wheels — grinds up the stumps and jungle growth, sets the firm foundation, forms the surface slabs, sets them in place, and the roadway bed is paved!

These forest highways now are bringing to the innermost depths of the tropic world the goods and materials of progress and prosperity — creating productive communities that can enter profitably the markets of the world, and offering to us all enchanting tours through the storybook forests of tropic lands.

The mountain barrier — legendary challenge of man — now invites communal living in a world of awesome beauty.

A new system of highways spans the continents, to transport men and goods swiftly and separately across the land.

And for our deserts, a new technology: waters from the sea — made fresh as rain — to nourish crops planted in the sand, produced from seed to shipment, programmed and processed by a new agriculture. A science of plenty for an ever-growing world!

People live today where they will. Neither terrain nor distance a deterrent to where the men of the city build their homes. All roads lead, as they have for centuries, to the great centers of commerce and communication, as the continental highway now leads us to the city of tomorrow!

Plazas of urban living rise over freeways. Vehicles, electronically paced, travel routes remarkably safe, swift, and efficient. Towering terminals serve sections of the city, make public transportation more convenient, provide ample space for private cars. And from a lower level, covered, moving walks radiate to shopping areas that are now truly marketplaces of the world — its traditions and its faiths preserved. There is new beauty and new strength in the city of tomorrow.

Making a (Really) Wild Geo-Engineering Idea Real - a16z Future podcast

Why Artificial Intelligence Isn’t Intelligent - Christoper Mims, WSJ

Effects of Big Tech Acquisitions on Start-up Funding and Innovation - Tiago S. Prado and Johannes M. Bauer

The Diffusion of Disruptive Technologies - Nicholas Bloom, Tarek Alexander Hassan, Aakash Kalyani, Josh Lerner, and Ahmed Tahoun

Japan to develop passenger spaceships in 2040s linking world's major cities in 2 hours - Mainichi Japan

Alphabet launches new robotics software company Intrinsic - CNBC

The fourth industrial revolution – this time it’s exponential! - Richard Jones, Soft Machines

How to Build High-Speed Rail with Money the United States Has - Alon Levy, Pedestrian Observations

What is solarpunk and can it help save the planet? - BBC

Tweetstorm of the Week: