🤖 AI is here. But AGI is not. And that's OK (for now)

Big economic gains are possible even without machines that think like humans

“Technology happens because it is possible.” - Sam Altman

The Essay

🤖 AI is here. But AGI is not. And that's OK (for now)

Sometime over the next week or two, SpaceX’s massive Starship could lift off for an orbital test flight. Now, I’m not a business consultant or hot-shot Wall Street investment analyst, but it seems to me that space might be in store for an emerging technology “hype cycle.” And a successful launch of what Elon Musk calls “the holy grail of space technology” — designed to be fully reusable— on top of its SuperHeavy booster might be the trigger mechanism. Orbit, the Moon, and Mars our destination.

Now I’m too young to have lived through Project Apollo and the space dreams of the 1960s. So this would be my first space hype cycle. But I’m old enough to have lived several previous hype cycles, or at least bouts of massive techno-enthusiasm: the PC, the internet, nanotechnolgy, iPhone applications, autonomous driving. Several of these involved artificial intelligence, from Deep Blue beating chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov in 1997 to IBM’s Watson winning on Jeopardy in 2011.

None of this is meant to be a statement of cynicism. The value created by the computer, internet, and smartphone combo is in the trillions of dollars. And I’m probably as excited and hopeful as anyone about the innovations we’re currently seeing in generative AI. It certainly seems as if things are moving quite quickly, from record early adoption rates to a flood of use cases. Over at online prediction platform Metaculus, the consensus forecast date of artificial generative intelligence now stands at February 1, 2032, versus April 14, 2052, back in early 2022.

But the optimism that fuels this newsletter does not depend on human-level AI, much less superhuman. That said, continued advances in machine learning are important to my thesis as is the continue effective diffusion of ML as a general purpose technology of significant important. And that diffusion process, aided by all manner of complementary investments. Stanford University economist Erik Brynjolfsson:

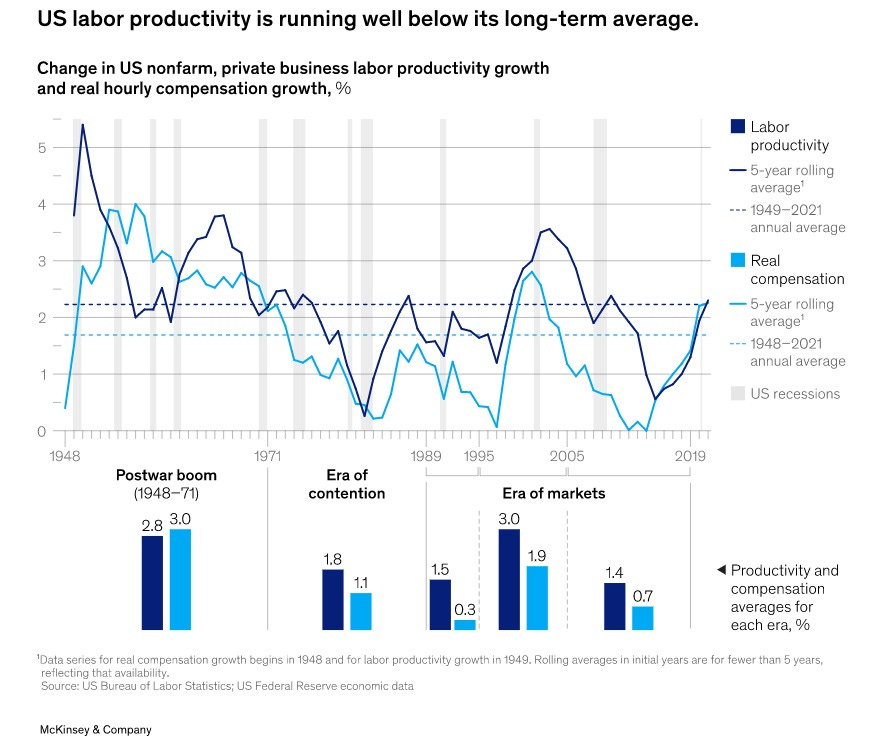

While advances in technology are the catalyst of productivity growth, that growth is not realized unless and until a cascade of complementary innovations are implemented. For instance, when American factories first electrified, there was negligible productivity growth for the first 30 years. It was only after the first generation of managers retired and a new generation replaced the old “group drive” organization of machinery, which was optimized for steam engines, with the new “unit drive” approach that enable assembly lines that we saw a doubling of productivity. Today, despite impressive improvements in AI, not to mention many other technologies, productivity growth has actually slowed down, from an average of over 2.4% per year between 1995-2005 to less than 1.3% per year since then. The bottleneck is not the technology – though faster advances certainly wouldn’t hurt – but rather a lack of complementary process innovation, workforce reskilling and business dynamism. Simply plugging in new technologies without changing business organization and workforce skills is like paving the cow paths. It leaves the real benefits largely untapped. However, by making complementary investments, we can speed up productivity growth.

That Brynjolfsson analysis comes from 2019, and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman made a similar point the other day, also citing the story of electrification as laid out in the famous 1990 economic paper “The Dynamo and the Computer” by economic historian Paul David. Heck, it was also three decades from the declaration of Moore’s Law to the start of the mid-1990s productivity boom. The headline from that Krugman essay, “A.I. May Change Everything, but Probably Not Too Quickly,” may have seemed like clickbait or trolling, but it was a reasonable statement.

Of course, I hope AI changes everything (well, things that can be changed for the better) — most notably decades of disappointing productivity growth — with great alacrity. As I wrote on Monday, the sorts of complementary investment one would need to see with AI/ML seems to be happening, especially in the areas tracked by the AI Index Report from the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI: AI-related hiring, investment, education, and skills penetration among others.

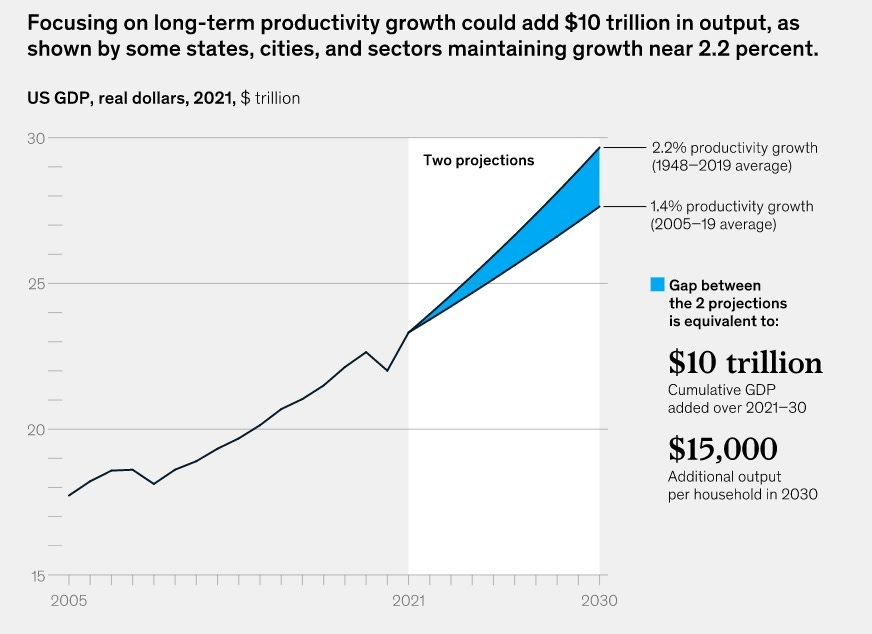

And if this investment process continues and we avoid bad decisions — such as taking an AI Pause — there’s good reason to think that faster productivity growth will emerge in the economic statistics sooner rather than later. Remember, we don’t need warp-speed growth or a pace of improvement such that the Technological Singularity is nigh. Labor productivity growth averaged 1. 1 percent annually in the decade between the Global Financial Crisis and the Global COVID-19 Pandemic and 1.4 percent over the decade and a half between the end productivity boom of 1994-2004 and the pandemic. But a return to the pace of productivity growth seen from the end of World War Two through the start of the pandemic. 2.2 percent, would have a pretty awesome economic impact:

Returning US productivity to its long-term trend of 2.2 percent annual growth would add $10 trillion in cumulative GDP over the next ten years. This is equivalent to every US household seeing a cumulative income gain of $15,000 over that period. Other things being equal, it would also boost stagnating median incomes and encourage labor participation.

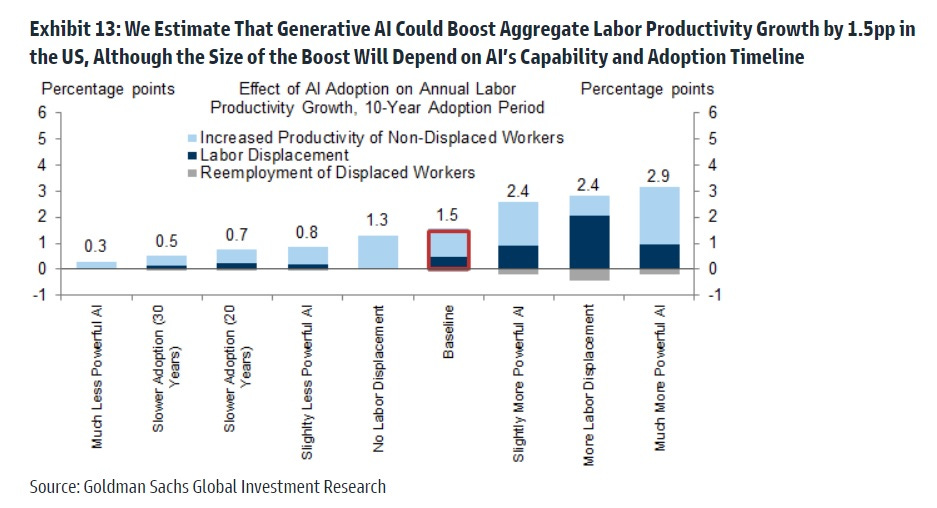

Let me again point to the recent Goldman Sachs analysis looking at GenAI. The bank thinks the emerging deep-learning technology could raise annual US labor productivity growth by just under 1½ percentage points over a 10-year period following widespread business adoption. Such a boost would create a long-term 3 percent economy (again), instead of a 1.5 percent economy (the long forecast of many economists), with productivity growth at the highest levels since the boomy late 1990s and early 2000s. GS:

Despite significant uncertainty around the potential of generative AI, its ability to generate content that is indistinguishable from human-created output and to break down communication barriers between humans and machines reflects a major advancement with potentially large macroeconomic effects. … The combination of significant labor cost savings, new job creation, and a productivity boost for non-displaced workers raises the possibility of a labor productivity boom like those that followed the emergence of earlier general-purpose technologies like the electric motor and personal computer. … Although the impact of AI will ultimately depend on its capability and adoption timeline, this estimate highlights the enormous economic potential of generative AI if it delivers on its promise.

GenAI might be an AI Revolution, but it’s not yet an AGI Revolution. Still, tremendous economic productivity gains might be possible from just this manifestation of AI/ML, especially with supportive public policy in areas such as immigration, R&D, and (light) tech regulation.

Micro Reads

▶ An AI ‘Pause’ Would Be a Disaster for Innovation - Bloomberg Editors, Bberg |

▶The case for an environmentalism that builds - The Economist |

▶The Robots Have Finally Come for My Job - Greg Ip, WSJ |

▶Congress Tries Again on Advanced Nuclear Energy - Leigh Anne Lloveras and Adam Stein, Breakthrough Institute |

▶The Chinese Talent Behind Your Favorite Generative AI Product - AJ Cortese MacroPolo |

▶The Counter-Reformation, Science, and Long-Term Growth: A Black Legend? - Matías Cabello, MLU Halle-Wittenberg

▶Capital Is Making a Comeback - Steven Bogden, WSJ Opinion |

▶How AI startups are fully automating drug discovery - Adam Green, Sifted/FT |