🤖⤴️ AI and extreme economic outcomes

'This could even entail explosive growth — an order-of-magnitude increase in the growth rate.'

Quote of the Issue

“Humanity has the stars in its future, and that future is too important to be lost under the burden of juvenile folly and ignorant superstition.” - Isaac Asimov

I have a book out: The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised is currently available pretty much everywhere. I’m very excited about it! Let’s gooooo! ⏩🆙↗⤴📈

The Essay

🤖⤴ AI and extreme economic outcomes

Think about a world in which a big chunk of white-collar work can be done at low or zero marginal cost, meaning there’s very little or no extra cost for each additional task or project. Or, going further, imagine a world in which the marginal cost of scientific and technological research, specifically, falls close to zero.

These two fascinating and important questions are the subject of a new report, “Assessing the Implications of a Productivity Miracle” by analysts at Bridgewater Associates. As the report sets things up:

Are we on the edge of a productivity miracle? This question is on our minds as we both observe and use cutting-edge machine-learning tools. As machine-learning solutions surpass human performance at many cognitive tasks that had previously been the exclusive domain of people, the odds are rising that the marginal cost of many economically important cognitive tasks will fall close to zero.

Let’s first take up the issue of AI and white-collar work where some jobs will be automated and some complemented, along with the creation of novel things for workers to do. Within that framing, some jobs would be expected to disappear. The classic example is agriculture, a sector that accounted for 85 percent of total US employment at the start of the 19th century vs. 1.4 percent today. But as you may have noticed, the 20th century was not a century of mass unemployment.

As the Bridgewater report explains: “Over the long run, productivity-enhancing technologies free up time and money to spend in new areas. Our workforce gradually expanded in other sectors as fewer people were needed to farm and consumer demand shifted.”

This economic phenomenon, the report notes, can also be seen historically with the Ford Model T automobile where the assemby line process lowered prices and spurred new demand and new industries elsewhere in the economy, as well as a mass consumer market for cars. From the report:

AI could similarly make a host of previously high-cost items very cheap to provide, such as tailored legal advice, customized software builds, individualized financial planning, and one-on-one tutoring. … We’ll likely see a mix of the two dynamics as AI lowers production costs: customers will buy more at the new lower price but will also spend some of their savings in other categories. Similar (though smaller scale) versions of these dynamics have occurred more recently. The automation of goods production in the 1990s and 2000s led to rising output as people bought more or higher-quality goods at lower prices, but higher goods consumption didn’t crowd out other forms of spending. In the later part of that period, durable goods even shrank as a share of consumer spending as people spent their savings elsewhere (especially in more discretionary services sectors).

Anyone projecting mass technological unemployment from AI automation has to contend with these historical examples and baseline economic reasoning. That said, the report’s other query would seem to take us into new territory: What about AI that can automate the process of knowledge advancement, a supersmart, super-capable research assistant? From the report:

An AI tool that could drive research on its own could add the equivalent of billions of human researchers to the R&D ecosystem, producing an innovation boom. The resulting growth would compound, as AI-powered researchers could further improve AI technology, and the rapid economic growth their inventions catalyze would make it possible to direct more resources toward creating even better AI tools. This world would be very different from those where AI capabilities do not progress as much; it could even entail “explosive growth,” i.e., an order-of-magnitude increase in the growth rate.

Yet the next iteration of ChatGPT probably won’t be sufficient to boost economic growth such that it would be, say, several multiples higher than the historical average. Full automation of the R&D process would probably need human-level artificial general intelligence, if not better, according to Bridgewater. If possible, however, AGI would eliminate a key constraint on technological progress: There are only so many scientists and technologists. And it appears that research productivity is declining, despite more resources being put to the task. (The number of researchers required to double computer chip density has increased 18-fold since the early 1970s.)

A good point here: “An AI that fell short of this threshold could still be incredibly fruitful for research but probably wouldn’t overcome some crucial hurdles to explosive growth. Past innovations with extensive uses in the R&D ecosystem—like software and the internet—have not produced a permanent shift in the pace of productivity growth.”

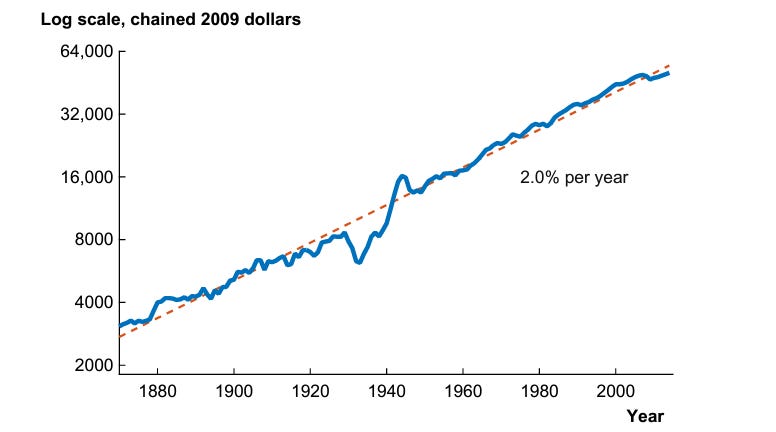

This is hardly a new phenomenon. Stanford University economist Charles Jones points out that since 1870, GDP per person in the US economy has grown at a “remarkably steady” average rate of around 2 percent per year, give or take.

And while you might create an economic model suggesting AGI would boost annual GDP growth to 20 or 30 percent, things probably wouldn’t be that simple. In a review of the really interesting 2021 Open Philanthropy analysis, “Could Advanced AI Drive Explosive Economic Growth?,” economists offered several caveats with the overall point that extraordinarily fast technological progress and growth might not lead to the expected increase in output growth due to these complex social and economic dynamics such these:

If living standards doubled every 2.5 years, people would be a thousand times richer in 25 years. This would require creating and deploying tech advancements far surpassing all historical achievements. Warp-speed growth would need warp-speed diffusion technology.

Rapid growth would lead to significant "creative destruction," including fast turnover in technology and worker skills, likely causing societal pushback.

With rapidly increasing incomes, people might reduce their work efforts. They might live off their growing investments, work significantly fewer hours, retire early, or take extended time off.

The report’s conclusion:

Forecasts about the development of AGI rest on highly speculative and untestable assumptions about how much more powerful models would need to become to develop humanlike intelligence. … [And] if we were to develop AGI, would it lead to explosive growth? Critics here point out that the testing and implementation of an AGI’s ideas would likely rely on processes that naturally take time or face resource constraints, like conducting experiments or sourcing and processing raw materials. Alongside potential obstacles from regulation or a lack of suitable training data for many tasks, these delays could prevent the rapid compounding that is necessary for explosive growth. Some say that super-advanced AI tools could just innovate their way out of these problems, but this claim is very challenging to assess from today’s vantage point. Given these considerations, full-blown explosive growth looks unlikely. But we wouldn’t rule it out at this early stage—and assigning it even a tiny probability would dramatically alter our average expectations for what the world will look like decades from now.

Of course, my pro-progress, Up Wing thesis really only depends on the American economy being able to grow as fast in the future as it has in the past — at least when really hitting on all cylinders. And what are the chances of that happening? Some good points on this issue from market strategist Edward Yardeni. In a recent research note, he highlighted the following investment stats, which are what you might expect to see if an AI boom were emerging:

High-tech spending on IT equipment, software, and R&D rose to a record $1.84 trillion (saar) during Q3-2023.

Such spending has hovered around a record 50% of total capital spending in nominal GDP since the pandemic, up from about 25 percent in1980.

During Q3-2023, R&D accounted for 20.2% of capital spending in nominal GDP, while software represented 17.2% and information processing equipment 12.1%).

It’s worth noting that Yardeni is bullish on the possibility of a productivity and economic boom, with AI a big part of the story. He sees productivity growth that would be spectacular — especially versus current expectations and recent history — but hardly science fictional:

In our opinion, the latest productivity growth boom cycle started well before the pandemic, at the end of 2015. During Q4 of that year, the 20-quarter annual average growth rate of productivity was only 0.6%, the slowest pace since the end of 1982. It almost tripled, rising to 1.6%, through Q4-2019, just before the pandemic. The pandemic at first boosted productivity growth (when layoffs soared), but then depressed it (when quits soared). During Q3-2023, this measure of productivity growth was back up to 1.8%. We think it is heading to 3.5%-4.5% by the end of the decade. That might seem far-fetched (maybe even delusional), but our heady targets are consistent with the comparable peak growth rates of the past three productivity boom cycles. And this one has more going for it, in our opinion, as noted above.

Faster, please!

Micro Reads

▶ Tesla Shows Off Optimus Gen 2 Robot With Improved Hands, Slimmer Figure - Vlad Savov, Bloomberg

▶ Green pledges mean nothing if you can’t get the permits - Brooke Masters, FT

▶ Cheating Fears Over Chatbots Were Overblown, New Research Suggests - Natasha Singer, NYT

▶ Tesla’s huge recall will make it harder — but not impossible — to misuse Autopilot - Andrew J. Hawkins, The Verge

▶ US nuclear regulators to issue construction permit for a reactor that uses molten salt - Jennifer McDermott, Power Engineering

▶ How to Use Challenge Prizes - Santi Ruiz, Statecraft

▶ China's economic decline has been vastly exaggerated - Branko Milanovic, UnHerd

▶ All habitable worlds come to an end - Avi Loeb, The Debrief

▶ The “Trolley Problem” Doesn’t Work for Self-Driving Cars - Sarah Wells, IEEE Spectrum

Although chip density itself may require more researchers, the more interesting research these days is around new kinds of accelerators (I'm finishing a Master's in this right now) which can improve performance outside the realm of the typical CPU.