A stunning week in science and tech; Roaring Twenties or Boring Twenties; telemedicine is here to stay; the story of human progress through nails; and much more ...

“The limits of the possible can only be defined by going beyond them into the impossible.”- Arthur C. Clarke

In This Issue:

⏩ A stunning week for tech progress in space, biology, and energy

🐢 What’s the risk of a Boring Twenties rather than a Roaring Twenties?

😷 Not only is telemedicine convenient, it doesn’t seem to hurt care quality or increase costs

📈 The power of human progress as told through the story of nails, the hammering kind

⏩ A stunning week for tech progress in space, biology, and energy

More videoconferencing and ecommerce aren’t going to create a “New Roaring Twenties” of fast productivity and economic growth. Nor is a post-pandemic economic reopening combined with a tsunami of stimulus cash. Not that those things are bad. Every little bit helps. It’s just that significant and sustained economic acceleration will need significant and sustained technological progress. What would that look like? Maybe something like this:

Only a week or so after Virgin Galactic founder Richard Branson took his rocket plane near the Kármán line, Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos on Tuesday took his rocket just past the space boundary. Of the two, the Bezos effort is the more intriguing. While Blue Origin’s New Shepard is a space tourism rocket, CNBC notes that the company “is also working on a massive orbital rocket called New Glenn, a stable of next-generation rocket engines, and a crewed lunar lander.” Also, Bezos is 40 times as wealthy as Branson and can simply invest more resources in his dream of building a diverse orbital economy (the production of exotic materials, solar power generation, and even asteroid mining).

Google-owned AI company DeepMind published a paper on Thursday showing its AlphaFold algorithm could confidently predict the structural position for almost 60 percent of amino acids, which in turn will allow researchers to predict the three-dimensional structure of proteins. There you go, one of biology’s “grand challenges” solved. And the experts seem wowed. The Financial Times quotes the director-general of European Molecular Biology Laboratory (which hosts the 350,000 protein structure prediction in a public database) this way: “Accurately predicting their structures has a huge range of scientific applications from developing new drugs and treatments for disease, right through to designing future crops that can withstand climate change, or enzymes that can degrade plastics. The applications are limited only by our imaginations.”

And speaking of “grand challenges,” the Wall Street Journal also on Thursday reported that Form Energy — a startup based in Somerville, MA, that’s backed by Bezos and Bill Gates — may have found a “holy grail” in the energy industry: a battery that would enable power grids to cheaply store large amounts of electricity for days — especially when the wind isn’t blowing or the sun isn’t shining. From the exclusive WSJ report:

On a recent tour of Form’s windowless laboratory, [CEO Mateo] Jaramillo gestured to barrels filled with low-cost iron pellets as its key advantage in the rapidly evolving battery space. Its prototype battery, nicknamed Big Jim, is filled with 18,000 pebble-size gray pieces of iron, an abundant, nontoxic and nonflammable mineral. Iron pellets that fill the battery are abundant and inexpensive and could hold electricity for days or weeks. … For a lithium-ion battery cell, the workhorse of electric vehicles and today’s grid-scale batteries, the nickel, cobalt, lithium and manganese minerals used currently cost between $50 and $80 per kilowatt-hour of storage, according to analysts. … Using iron, Form believes it will spend less than $6 per kilowatt-hour of storage on materials for each cell. Packaging the cells together into a full battery system will raise the price to less than $20 per kilowatt-hour, a level at which academics have said renewables plus storage could fully replace traditional fossil-fuel-burning power plants. … In 2023, Form plans to deploy a one-megawatt battery capable of discharging continuously for more than six days and says it is in talks with several utilities about battery deployments.

In other words, it was a bad week for [Greta] Thunbergians out there, those scarcity-obsessed pessimists who rail against “fantasies of infinite growth” — they think such growth either a scientific impossibility or environmental disaster. The “limits to growth” people continue to push their message of gloom with barely a hint of uncertainty. Note this Vice piece from a couple of weeks ago: “MIT Predicted in 1972 That Society Will Collapse This Century. New Research Shows We’re on Schedule.” It summarizes a paper from Gaya Herrington, an analyst at “Big Four” accounting firm KPMG, that reviews the modeling from the original “Limits to Growth” study and concludes, as Vice puts it “that the current business-as-usual trajectory of global civilization is heading toward the terminal decline of economic growth within the coming decade—and at worst, could trigger societal collapse by around 2040.”

But it’s not all bad news. Herrington thinks the rise in “environmental, social and good governance priorities” is reason for optimism. I, on the other hand, would point to technological progress, like the advances mentioned above, as reason for optimism. Likewise, I would point to the new issue of The Economist, which offers favorable words about climate engineering in a big piece about climate change, a helpful plank in creating a public permission infrastructure about a controversial policy: “It is also prudent to study the most spectacular, and scary, form of adaptation: solar geoengineering. … Research over the past 15 years has suggested that solar geoengineering might significantly reduce some of the harms from greenhouse warming.”

🐢What’s the risk of a Boring Twenties rather than a Roaring Twenties?

The previous essay mentions lots of emerging technologies that could, over the longer run, increase human welfare and boost the environmentally sustainable pace of economic growth. But we shouldn’t assume that will be the case. Maybe they’ll amount to nothing. Maybe, for instance, the machine-learning revolution will turn out to be not so revolutionary. Maybe we’ll enter another AI winter. Maybe the space economy will get stuck on the pad. Maybe the promise of genetic editing will remain unfulfilled. A Boring Twenties rather than a Roaring Twenties.

That’s why policymakers must constantly push pro-progress policies and always evaluate ideas — immigration, deregulation, science investment, tax reform, trade — through the lens of their potential to strengthen America’s innovation capacity. But aren’t we doing that right now with President Biden’s expansive economic agenda? Won’t that radically transform the American economy?

It’s hard to see such a transformation in the economic modeling, even in those with a bullish slant. For example: Mark Zandi, the well-known Moody’s Analytics economist has lots of good things to say about both the administration’s infrastructure plan and its proposed reconciliation spending on items such as early childhood and higher education, child and elder care, housing, healthcare, and climate change mitigation. From a recent Moody’s analysis:

The nation has long underinvested in both physical and human infrastructure and has been slow to respond to the threat posed by climate change, with mounting economic consequences. The bipartisan infrastructure deal and reconciliation package help address this. Greater investments in public infrastructure and social programs will lift productivity and labor force growth, and the attention on climate change will help forestall its increasingly corrosive economic effects. Moreover, the policies being considered would direct the benefits of the stronger growth to lower-income Americans and address the long-running skewing of the income and wealth distribution. Passage of legislation is far from certain but failing to pass legislation would certainly diminish the economy’s prospects.

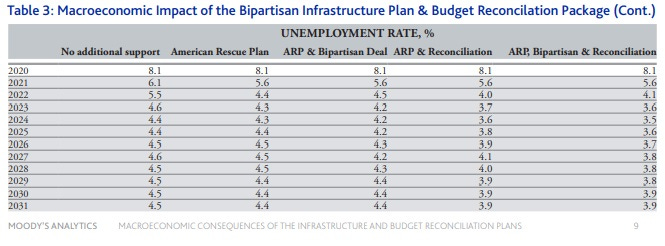

Zandi’s modeling considers a number of different legislative scenarios:

The first scenario assumes that Biden was unable to enact any major fiscal policy changes, including the American Rescue Plan that was passed into law in March.

The second scenario assumes that lawmakers fail to pass any additional fiscal policy legislation beyond the ARP.

The third and fourth scenarios assume the bipartisan infrastructure deal and the reconciliation package are each passed into law, respectively, but not the other. And the final scenario assumes that both the bipartisan infrastructure deal and the reconciliation package become law.

And here is the modeling, first for real GDP, unemployment rate, and labor force participation rate:

The bottom line from the above charts is faster growth in the near term with greater government action, but then the economy settles back into a longer-term 2 percent-ish pace. Also less unemployment and higher labor force participation. A few things:

First, in an economy as big as America’s, every tenth of a point in growth is meaningful. Second, growing rapidly for a short period and then settling back into the pre-blip pace still means greater additional growth since it comes from a higher plateau. Third, I probably have more concern than Zandi about the level of spending — particularly, from the $3.5 trillion reconciliation package — causing an inflation upturn that risks a policy error from the Federal Reserve and prematurely ends the expansion. Fourth, and most importantly, policymakers should look at the unspectacular long-term growth rate and find it totally unacceptable.

😷 Not only is telemedicine convenient, it doesn’t seem to hurt care quality or increase costs

Pew Research recently interviewed nearly a thousand “innovators, developers, business and policy leaders, researchers and activists” about life in 2025. One common theme that emerged was the broad adoption of “tele-everything” — including telework, telemedicine, virtual schooling, and e-commerce — as one long-lasting impact from the Covid-19 pandemic.

I see some of these tele-sectors as more significant than others. For instance, we certainly learned a lot about virtual schooling — though often what we learned was that remote school works poorly for many students. Another sector is ecommerce, and gains there might well prove persistent. A Goldman Sachs analysis recently noted that retail ranks high among sectors in terms of pandemic productivity performance, “consistent with a boost from ecommerce and from evolving brick-and-mortar business models [such as] expanding curb-side pickup. Moreover, timely data indicate these gains persisted in Q2 even as malls reopened and the stimulus boost faded.”

Telemedicine also seems promising going forward. The sunny conclusion of those Pew experts is supported by new research. In the VoxEU analysis “The impacts of the shift to telemedicine” by Dan Zeltzer, Liran Einav, Joseph Rashba, and Ran Balice conclude the pandemic made it more likely that telemedicine will be an important part of healthcare delivery. (Fun fact: Before the first lockdown, telemedicine accounted for about 5 percent of all primary care visits, then peaked at around 40 percent during the lockdown and remained at around 20 percent during the post-lockdown period). From that analysis (bold by me):

We find that access to telemedicine results in a slight increase in primary care utilisation (3.5% over the pre-COVID-19 baseline) and no significant increase in overall costs. The evidence is inconsistent with the concerns of increased care intensity, as we find that patients with access to telemedicine appear to receive less intensive treatment; they receive slightly fewer prescriptions and referrals and spend overall 5% less on healthcare services during the 30 days following an initial primary care visit. Although patients with access to telemedicine are 8% more likely to follow up with a physician within a week of the initial visit, the bulk of these follow-ups are with the same physician that provided the initial visit and they tend to be done remotely, so care continuity does not seem to be compromised.

We analyse more granularly the impact of increased access to telemedicine on the diagnosis of specific medical conditions – urinary tract infection, heart attack, and trauma (conditions that are common, unrelated to COVID-19, and may result in serious consequences if misdiagnosed). We find no evidence for decreased accuracy or increased likelihood of adverse events. Taken together, these results suggest that the increased convenience of telemedicine does not compromise care quality or raise costs.

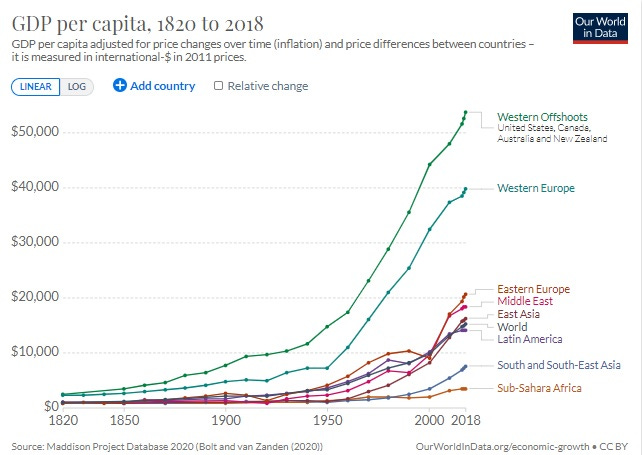

📈 The power of human progress as told through the story of nails

The stunning impact of the Long Industrial Revolution (including First, Second, and Digital) can be illustrated in a number of ways. Perhaps my favorite is this chart showing the increase in per capita GDP, adjusted for inflation:

The radical improvement can also be shown in jaw-dropping stats about key parts of our economic life, such as the real cost of lighting falling by a factor of 3400 from 1800 to 1992. Then there’s the real cost of computing, which fell by a factor of at least 2 trillion times from 1850 to the early 2000s. Both those stats can be found in a new paper by economist Daniel E. Sichel of Wellesley College. But the focus of the paper is on a more pedestrian product: the humble nail. While nails produced in ancient Rome look much like the ones produced today, the production process has changed a lot —and so has the cost. From “The Price of Nails since 1695: What Can We Learn from Prices of a Simple Manufactured Product?”:

… the manufacturing process for nails has changed dramatically, with a shift from artisanal to factory production, a change in power source from hand to water to steam to electricity, and a shift in materials from iron to steel. Coincident with those changes, the price of nails fell significantly, as evidenced by the price index for nails that is constructed back to 1695 and that is the focus of this paper. Indeed, the real price of nails (relative to an index of overall consumer prices) fell by a factor of about 10 from the late-1700s to the middle of the 20th century, averaging a decline of about 1-1/2 percent a year. While these declines are paltry compared with those for lighting or computation, even basic manufactured products experienced large price declines, and an individual nail today seems cheap and disposable

It’s a story of both lower material prices and higher productivity (from the specialization of labor and re-organization of production processes). Another wild stat: “The share of nails in GDP dropped from 0.4 percent in 1810 to de minimis share today.” From a slide deck about the paper:

The COVID-19 Pandemic and the $16 Trillion Virus - David M. Cutler and Lawrence H. Summers | “As the nation struggles to recover from COVID-19, investments that are made in testing, contact tracing, and isolation should be established permanently and not dismantled when the concerns about COVID-19 begin to recede.

On the market for a supersonic airliner - Matthew Sattler, Incubate Aerospace | “Certifying a new transport category airplane is a risky, multi-billion-dollar endeavor. Yet today, more than ever before, hard tech businesses are thriving.”

The state of next-generation geothermal energy - Eli Duorado | “If we play our cards right, human civilization could soon have access to a virtually inexhaustible supply of cheap and clean energy. Shouldn’t we pull out all the stops to get there?”

What Would Hayek Do About Climate Change? - Mark Sagoff | “Entrepreneurs who are piling on to create clean energy sources exemplify the creative and dynamic nature of markets, as management guru Peter Drucker describes it, to organize and apply knowledge to knowledge to get things done”

From Twitter: A tweetstorm about nuclear fusion - @willjack |