A New Roaring Twenties would make America better, as well as richer

Also: Given cheaper solar power, do we need nuclear fusion?

"The only limit to our realization of tomorrow will be our doubts of today. Let us move forward with strong and active faith." - President Franklin D. Roosevelt

In This Issue

The Micro Reads: WFH and superstar cities, the rise of robot workers, better R&D, and more . . .

The Short Read: Given cheaper solar power, do we need nuclear fusion?

The Long Read: A New Roaring Twenties would make America better, as well as richer

The Micro Reads

🏙 “Superstar Cities Are (Probably) Immune From WFH” - Bloomberg | Columnist Justin Fox conducts a deep-dive interview with economist Enrico Moretti, who expounds on the what appears to be the consensus economist view of America’s high-productivity hubs in the post-pandemic era:

I think our link to the office will look a lot like in the past. There will be probably more work from home, but it might take the shape of one or two days a week, meaning that we still have to show up at the office three or four days. That’s fundamental because it means that for places like New York or San Francisco, if you want to have access to the types of careers and jobs and employers that are there, you still need to have a physical presence in the metro area. Maybe not next to your employer, given that you don’t have to commute every day, but in the same metro area.

🤖 “Robots replace humans as labour shortages bite” - Financial Times | This is more a story about labor shortages than labor costs. Also, efficiency. From the piece: “In US and European warehouses, the boom in online shopping during the pandemic has accelerated the switch to automated systems and robots, which can cope more quickly and efficiently with increasingly complex orders as demand for next-day delivery rises and bottlenecks in the supply chain cause disruptions.”

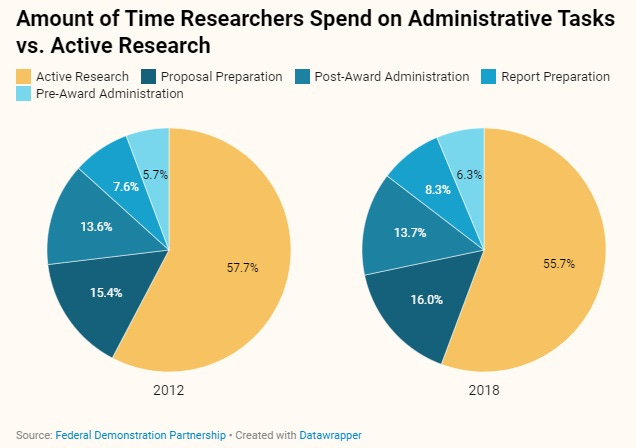

🔬 “Fix Science, Don’t Just Fund It” - Tony Mills, Innovation Frontier Project | Innovation policy isn’t just about higher government R&D funding levels. More taxpayer dough “won’t solve issues of concentration, bureaucratization, and replication in science,” Mills writes, adding that it is “striking how little attention has been paid to any of these issues in the current debates about boosting American science and innovation.” As this chart from the piece shows, the problem isn’t getting better despite its wide acknowledgment:

🌌 “The New Space Empires” - Anton Howes, Age of Invention | From the excellent piece: “There are quite a few parallels I can see between travelling to Mars, say, in a hundred years’ time, and travelling between continents in the age of sail. . . . it seems likely that those controlled by particular companies or countries may occasionally be persuaded — by bribes or by force — to defect. . . . [Such] problems curtailed the ambitions of other would-be colonial powers, like the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. When the Dutch turned up in the Indian Ocean, many of the Portuguese forts they threatened simply surrendered.”

📱 Tweet of the Issue:

The Short Read

⚛ Given cheaper solar power, do we need nuclear fusion?

A skeptic might call nuclear fusion “the energy of the future — and it always will be.” And while that future of limitless, clean (including both carbon pollution and radioactive waste) energy isn’t yet here, it might be rapidly approaching. This New York Times headline from a year ago, “Compact Nuclear Fusion Reactor Is ‘Very Likely to Work,’ Studies Suggest” has been followed by more big advances, especially by the burgeoning private sector that’s building upon previous government basic research.

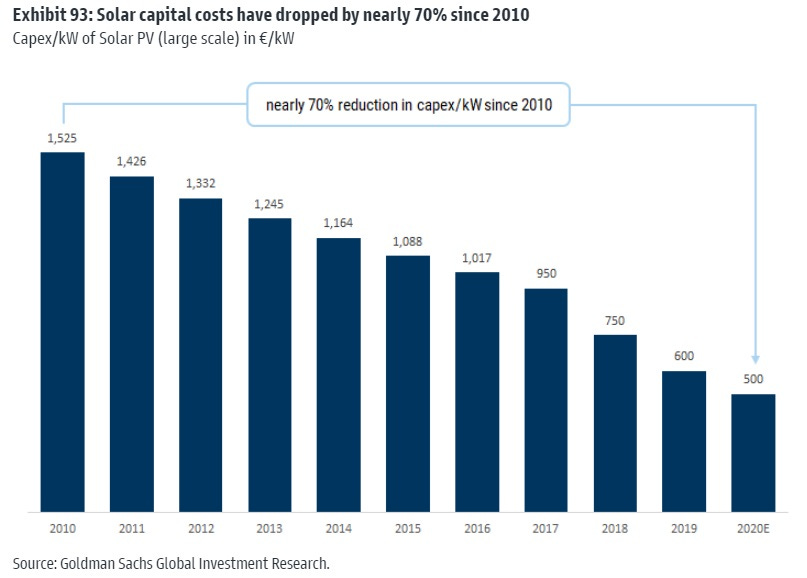

But nuclear fusion is hardly the only energy technology that’s seen big progress, as renewable energy advocates are quick to point out. Wall Street, too. Goldman Sachs noted this in a sector review at the start of the year: “Solar PV power generation costs have seen a remarkable decline over the past ten years,” a drop driven by subsidized Chinese manufacturing (including forced labor) rather than Moore’s Law-type of innovation.

But cheaper is good, even if costs have begun to stabilize in the longer term (and of late they’ve actually risen, partially due to pandemic-related supply chain issues). So some solar enthusiasts might wonder why we should spend considerable time, money, and intellectual bandwidth on trying to reproduce the power of the sun when we can just do more of what we already know how to do: capture its energy when it arrives on earth.

A great response to that query can be found in the optimistic-but-also realistic The Star Builders: Nuclear Fusion and the Race to Power the Planet by Arthur Turrell, whose work at the UK’s Office for National Statistics combines methods from data science, economics, and physics. (I just podcasted with him, by the way, an episode that should be posted within a couple of weeks.) Turrell say he’s not anti-solar, nor are the “star builders,” what he calls the researchers and entrepreneurs featured in his book. But solar and wind “can’t provide energy at the scale, growth rate, and level of consistency that is needed to power the entire planet,” he writes, adding that few experts believe “solar power will be able to supply more than 50 percent of electricity worldwide.”

Let’s just take one of those issues, consistency. From the book:

Even if solar panels were pasted across most of the landscape, they’d still be vulnerable to the weather. Solutions could include building cross-continental power transmitters or smoothing out the uneven supply of electricity using enormous batteries. Unfortunately, those big batteries don’t yet exist. Tokamak Energy CEO Jonathan Carling is skeptical that batteries will ever do the job. “You can have a battery that extends the day a bit,” he told me, “but to have a battery that turns winter into summer is too much to ask.”

Indeed, there’s already widespread concern about looming shortages of battery materials lithium and cobalt as the electrification of the global automobile fleet accelerates. This from Bloomberg:

And though cobalt is currently the most valuable battery metal, and the one with the most concerning supply chain, building enough powertrains for a global post-internal-combustion car fleet is going to require a lot more of a lot of metals: nickel and lithium for the cathodes, copper for the wiring, rare earths for the powerful magnets that turn the battery’s electrical energy into torque. Add up all of that, and subtract the world’s known reserves, and you get $10 trillion in what House calls “missing metals.”

Maybe automobiles and trucks would be a better use of those metals than mega-batteries for the electrical grid, which could be better powered by advanced fission, fusion, and geothermal.

The Long Read

😇 A New Roaring Twenties would make America better, as well as richer

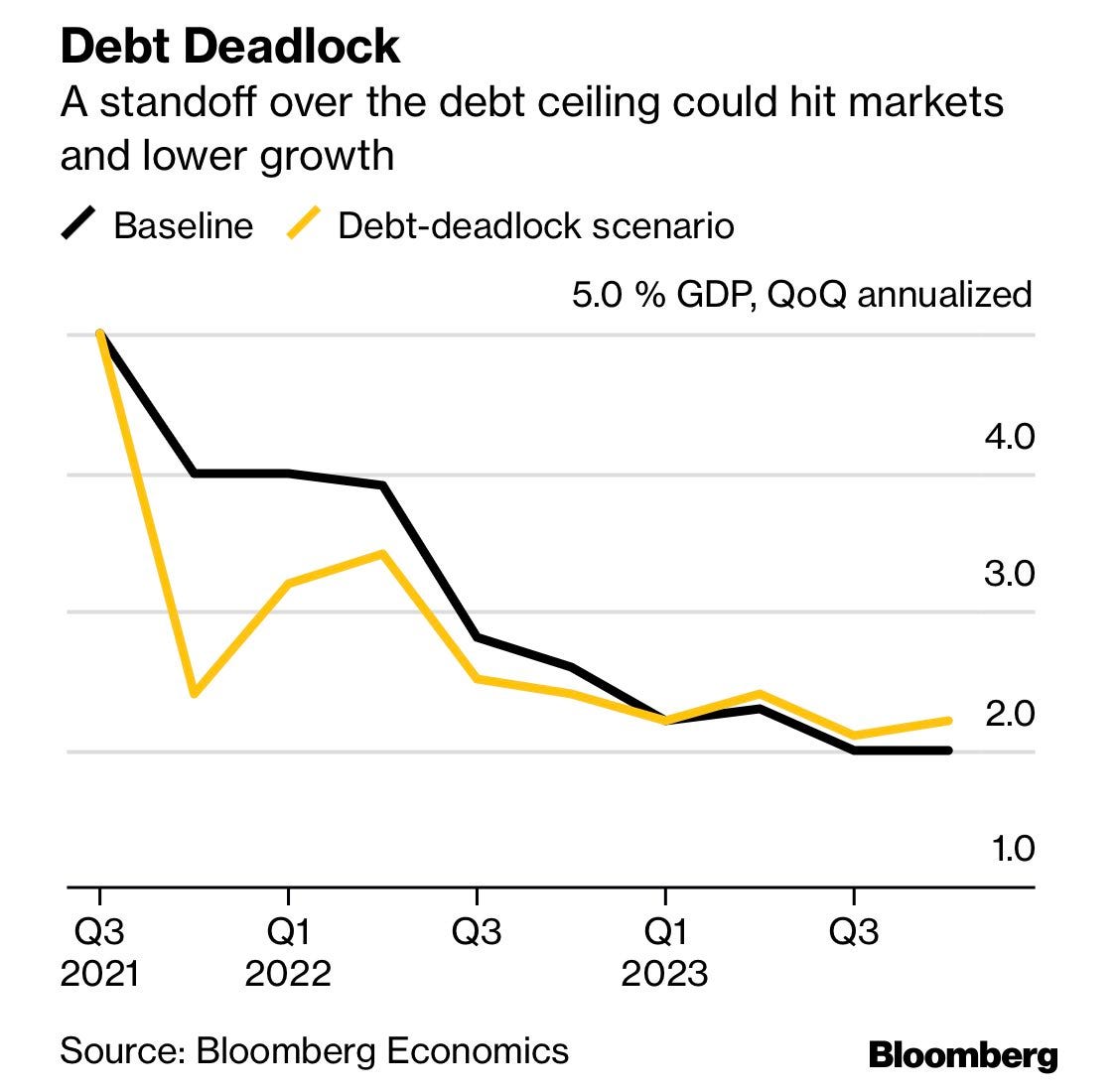

The following chart from the Bloomberg economics team forecasts the potential economic impact from congressional inaction over the debt ceiling. A late-year slowdown, basically, followed by return-to-trend growth. (So, not good.) Now what I really want you to notice here is the post-debt deadlock trend. Hello, again, to a Two Percent Economy™.

Obviously, I think the American economy can do better. That’s the whole point of this newsletter. And maybe America will do better thanks to pandemic-related productivity boosts (work-from-home, ecommerce) as well as the greater diffusion and use of digital technologies such as machine learning. And long-term advances in biotechnology, energy, and space could provide a sustained boost to human welfare, both here and elsewhere. (Abundant clean energy! Curing Alzheimer’s! Orbital factories! Flying cars!) Again, this newsletter spends considerable time analyzing those potential impacts.

But also important is how economic growth makes us better people and a better nation. One example: A new analysis by MIT economist Daron Acemoğlu and team of fellow researchers looks at the health of global democracy. And to be honest, its health could be better. The researchers note that the democracy advocacy NGO Freedom House reports how democracy has been in retreat globally for 14 consecutive years. That disturbing news led Acemoğlu and his team to ask a question: What makes people supportive of democracy? And here’s what they found:

Most importantly, our results establish that the association between exposure to democracy and support for democracy is driven almost entirely by people’s experience of successful democracy. In particular, it is exposure to democratic regimes that deliver economic growth, peace and political stability and public services that makes people more willing to support democracy. In contrast, greater exposure to democracies that are not hampered by deep recessions, mired in political instability, or unable to provide public services does not appear to increase support for democracy.

To be clear, economic growth isn’t the only thing that matters. It’s part of a package of achievements that make people support democratic governance. Of course, one would probably guess that solid economic performance would give people greater confidence in government. On the other hand, economic shocks and stagnation would do just the opposite, lowering confidence in both democracy and economic openness. The 2015 paper “Going to extremes: Politics after Financial Crises, 1870–2014” finds that after a severe financial crisis, “voters seem to be particularly attracted to the political rhetoric of the extreme right, which often attributes blame to minorities or foreigners. On average, far-right parties increase their vote share by 30 percent after a financial crisis.”

The authors of that paper probably weren’t that surprised by the results of the 2016 election. A 2019 Reuters analysis found that real GDP growth in 2016 in the 2600 counties won by Trump barely topped 1 percent vs. nearly 2 percent in the counties carried by Hillary Clinton. Stagnation is good for nativist populism.

Perhaps the most well known analysis of the impact of economic growth on the nature of a society is the 2005 book The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth by Harvard University economist Benjamin Friedman. It tells a compelling, intuitive story — supported through a deep political and economic analysis of American and Western European history — about how economic growth boosts social justice, while economic hardship promotes retreat from values such as tolerance for racial and ethnic differences, concern for the poor and disadvantaged, and civil liberties. Friedman writes:

The experience of many countries suggests that when a society experiences rising standards of living, broadly distributed across the population at large, it is also likely to make progress along a variety of dimensions that are the very essence of what a free, open, democratic society is all about. Conversely, experience also suggests that when a society is stagnating economically — worse yet, if it is suffering a pervasive decline in living standards — it is not only likely to make little if any progress in these social, political, and (in the eighteenth-century sense) moral dimensions; all too often, it will undergo a period of rigidification and retrenchment, sometimes with catastrophic consequences.

Again, this seems intuitive. You don’t have to be an economic historian to connect the launch and success of the Great Society and civil rights movement with the rapid economic and productivity growth of the 1960s. But if you’re looking for something more empirical, I would point to the aptly titled “The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth: An Empirical Investigation” by Lewis Davis and Matthew Knauss of Union College. The 2011 analysis tests Friedman’s hypothesis by using the World Values Survey to measure the demand for egalitarian social policy by support for the statement: “The government should take more responsibility to ensure that everyone is provided for.” From that paper:

In The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth, Benjamin Friedman argues that growth reduces the strength of interpersonal income comparisons, and thereby tends to increases the desire for pro-social legislation, a position he supports by drawing on the historical records of the US and several Western European countries. We test this hypothesis using a variable from the World Values Survey that measures an individual’s taste for government responsibility, which we interpret as a measure of the demand for egalitarian social policy. . . .Using this measure, we find strong support for a modified version of Friedman’s hypothesis. While the relationship between the rate economic growth and the taste for government responsibility is not significant, we find support for a positive and robust relationship between the taste for government responsibility and the change in the growth rate. Thus the demand for egalitarian social policy appears to be high not when the growth rate is high, but when the growth rate is rising. A similar result applies to income inequality: the demand for egalitarian social policy is low not when inequality is high in an absolute sense, but when it is high relative to its long run average.

So what’s described here is a sort of “policy treadmill” where acceleration is associated with egalitarian social policy. One policy conclusion you could draw is that when growth is booming, it’s a good time to push through policies that focus on increasing economic opportunity, boosting economic openness, and strengthening the safety net. So faster, please!