🌎 6 Down Wing myths about the American economy and the world

Economist Larry Summers just gave an enlightening speech about a host of economic misconceptions. And I am on it!

Quote of the Issue

"Nations and their economies grow in large part because they increase their collective knowledge about nature and their environment, and because they are able to direct this knowledge toward productive ends." - Joel Mokyr, A Culture of Growth

Some self promotion: I have a book coming out on October 3. The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised is currently available for pre-order pretty much everywhere. I’m very excited about it! Let’s gooooo! 🆙↗⤴📈

The Essay

🌎 6 Down Wing myths about the American economy and the world

A key part of my Conservative Futurism is trying to understand as accurately as possible the world we currently live in and how we got here. If we get that wrong, it’s going to be nearly impossible to create the best possible conditions for future progress. (“Study the past if you would define the future,” as Confucius put it.) And that just isn’t the Northwestern University history major in me talking!

So given my perspective, I have to thank my AEI colleague Stan Veuger, a brilliant economist, for tipping me off to a lecture that Lawrence Summers, also a brilliant economist as well as former US Treasury Secretary, gave on Monday at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. The title of the presentation was “What should the 2023 Washington Consensus be?,” a reference to the turn-of-the-century policy reforms — such as market liberalization, fiscal discipline, and privatization — typically offered to troubled developing countries by the IMF, World Bank, and US Treasury Department.

Summers started out by framing the Washington Consensus as the principles that “undergird or have undergirded American international economic policy since the end of the Second World War.” He then noted that his old boss President Bill Clinton had wondered whether post-Cold War America would repeat the mistakes that were made after World War I or “recreate the successes” in the period since World War II. Summers then continued:

[Clinton], I'm sure, imagined at that time that by 2023 the answers to those questions would be clear. And yet I think they are not completely clear, and I think the prospects that history will see us as having gotten it right are not as large as those prospects looked one or two decades ago. I would suggest six misconceptions that pervade a great deal of the current economic debate.

And here are those misconceptions as outlined by Summers with some commentary by me:

1/ Summers: “First, it is supposed that the idea of economic policy is to maximize the creation of jobs rather than to maximize the availability of goods at low cost to consumers and firms. Both the officials responsible for competition policy and those responsible for international trade have explicitly rejected economic efficiency as a central guide for economic policy. This, I would suggest, is a costly and consequential error. All the more, it is a costly and consequential error at a time when the ratio of job vacancies to unemployment is higher than it has been any time in the last 40 years. And all the more, it is a costly and consequential error at a time when high cost of living is a central concern of the American public.”

➡ Me: I interpret this misconception as a firmly worded critique of the Biden administration’s embrace of industrial policy and its continuation of the unfortunate trade protectionism of the previous administration. Such policies are often promoted as creating “good jobs here at home.” And while that promise sounds appealing, economic efficiency and productivity growth are what raise living standards over the long term. Directly targeting specific industries for government subsidy or tariff protection can a) misdirect resources away from potentially superior economic uses and b) hinder the growth of emerging sectors by trying to maintain jobs in lagging industries. Without competitive intensity that comes from open market competition among both domestic and international firms, a company or sector will, you know, become less competitive! What’s more, when governments selectively back certain sectors, they risk "picking winners" where decisions are influenced more by politics than sound economic logic.

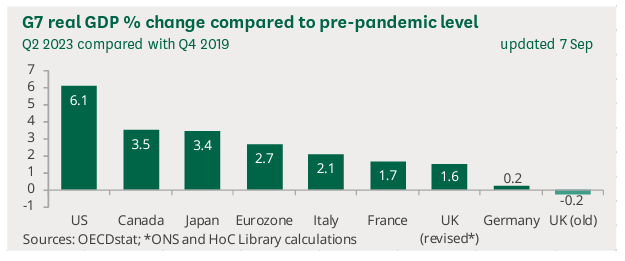

2/ Summers: “The second misconception is that these have not been good decades for the American economy in international perspective. I first got to know my friend Ted Truman well when he was long into his career as the head of the Federal Reserve's International Economic Section and I was a new undersecretary of the Treasury for international affairs. We were involved in making various long-term economic projections for the world. None of them would have believed that US GDP as a share of global GDP would have remained robust for the entirety of the next generation. And if we had been told how spectacularly China was going to do over the next 30 years, we would have been that much more pessimistic. We could not have imagined that the share of US wealth, reflected heavily in the stock market, would have been far higher a generation later than it was at that time.

“The truth is that the United States has done extraordinarily well. It could have been argued until a few years ago that if you looked at what's probably the single best measure of an economy's performance, its GDP per person between the age of 20 and 65, that we had not done so well. But if you look up till now, we have actually done very well on that standard as well. So, there are plenty of internal issues. But as an overall economy, the United States has fared very well.”

➡ Me: I would point out a few things here. First, over the past two decades, wages for the typical American worker have risen in real terms by more than a fifth — including the chaos of the pandemic years. Second, predictions that China will someday overtake the US economy in total GDP are looking evermore shaky. Third, this chart shows American outperformance versus other rich nations, as well as China:

3/ Summers: “Third, the world has fared very well. Relative to the time when I was chief economist of the World Bank at the beginning of the 1990s, child mortality rates are less than half of what they were then. Literacy rates are more than twice what they were then. Poverty rates, in terms of extreme poverty, are less than 40% of what they were then. And in some ways most fundamental and important, this month, we celebrate the 78th anniversary of a situation where there has been no direct war between major powers. You cannot find a period of 78 years since Christ was born when that was the case. So, the idea that we've been doing it all wrong is, I would suggest, a substantial misconception.”

➡ Me: I know the anti-capitalists hate this chart, but it is what it is:

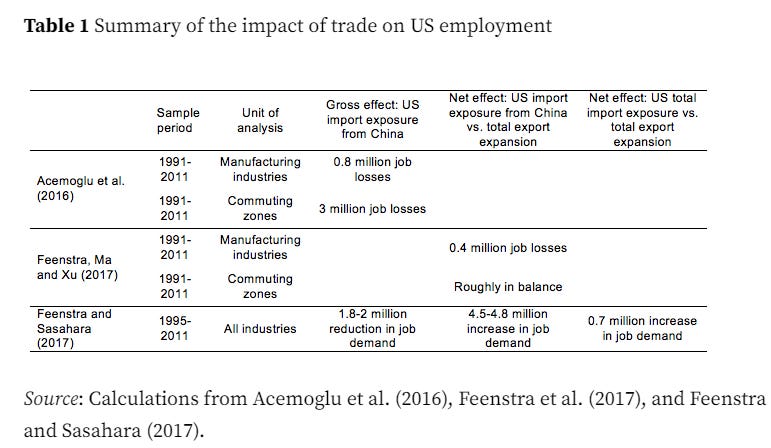

4/ Summers: “Fourth, the problems that we have are not due to trade liberalization. The single most misleading idea that has moved from academic economic research into the popular domain is the concept of the China shock associated with China's accession to the WTO. To start with, that agreement did not change one iota of US policy permitting Chinese goods to be sold in US markets. The principle that China would be the beneficiary of most favored nation treatment and get the same benefits that other countries did had been well established years before. It was ritually reaffirmed annually by the Congress.

“Yes, China's tremendous economic progress did lead to far more sale of goods in the United States. But it is hard to imagine a less credible approach to the problem than adding up all the losers from the imports without taking any account of the jobs created and the economic impacts of the goods we sold to China, of the lower-cost inputs we received because of imports from China, of the enhanced real wages and associated greater spending caused by those lower prices, and the lower capital costs associated with the inflows of capital that we received from China. When those calculations have been done, as they've now been done by Rob Feenstra and several other teams of economists, they show that, in fact, as with NAFTA, the net benefit to the US economy has been substantial.”

➡ Me: Summers here is referring to the work of University of California, Davis economist Robert Feenstra who looked at the job losses due to China’s imports as well as job gains from US global exports, finding that the two largely offset each other in the 1990s and 2000s. In other words, a victory for Econ 101 which holds that opening up trade between countries has two main effects on jobs. First, companies that now face competition from imports may get smaller or even go out of business, leading to lost jobs. Second, companies that can now export more products to other countries may grow and add more jobs. Feenstra:

Our results fit the textbook story that job opportunities in exports make up for jobs lost in import-competing industries, or nearly so. Once we consider the export side, the negative employment effect of trade is much smaller than is implied in the previous literature. Although our analysis finds net job losses in the manufacturing sector for the US, there are remarkable job gains in services, suggesting that international trade has an impact on the labour market according to comparative advantage. The US has comparative advantages in services, so that overall trade led to higher employment through the increased demand for service jobs.

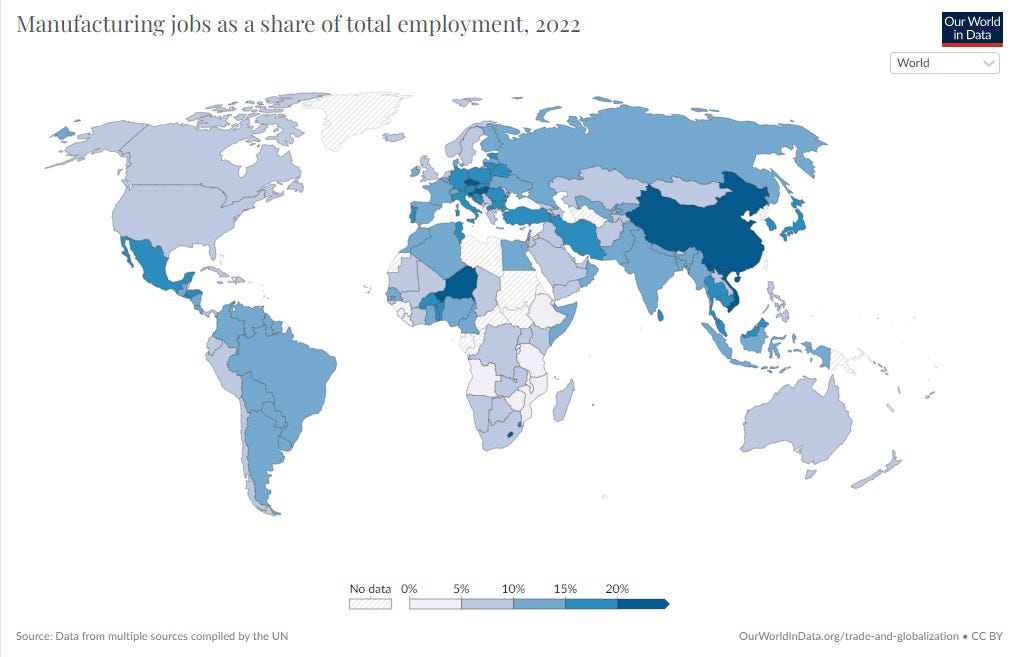

5/ Summers: “The fifth misconception is that domestic industrialization and some kind of renaissance of manufacturing is somehow the central issue for US prosperity going forward. This is simply not a realistic idea. In 1970, about 20% of US workers were engaged in production work in manufacturing. Today, that number is about 6%. That number has trended downwards in countries like the United States that have tended to run trade deficits. It has also trended downwards rapidly in countries like Germany that have run manufacturing, export, mercantilist-oriented economic strategies and not at very different rates. It is a consequence of the same set of phenomena that led to declining shares of workers in agriculture over time. … And there is nothing in the coming robotic revolution to suggest that these trends are likely to do anything other than accelerate going forward. I would note that the president of Ford has judged that it requires about 40% less labor input in a Ford factory to make an electric car as to make a traditional car.

“I am aware that we have a much-ballyhooed increase in manufacturing plant construction going on in the United States, and that that figure has shown almost a hockey-stick level of growth. I'm also aware that of the 30 categories of business investment, that category is one of the very smallest, and that it constitutes less than 2% of total business investment. The idea that we can build an economy on growing our manufacturing sector is just not realistic and it is potentially counterproductive. I would just note that there are about 100 times as many workers in steel-using industries as there are in the steel industry as evidence of the potential costs of domestic content requirements motivated by the desire to create capacity.”

➡ Me: Again, I think charts plainly tell the story here, both in the US and globally:

6/ Summers: “Finally, I would suggest that substantial and accumulating deficits and debts are a substantial threat to national security and national power, contrary to what is often believed in what sometimes seems like a post-budget constraint era of economic thinking. … Suffice it to say that a reasonable calculation would suggest that our budget prospects are vastly worse than they were at the time of the Clinton administration's successful budget actions and substantially worse than they were at the time of the Simpson-Bowles efforts. The budget deficits a decade out comfortably in double digits as a share of GDP now seem a reasonable projection with primary deficits quite likely in the 5% of GDP range. This is without the assumption of the need for vast mobilization for meeting contingencies, military or non-military. And I think it is reasonable to ask the question: How long can or will the world's greatest debtor be able to maintain its position as the world's greatest power?”

➡ Me: I get that it’s more fun to assume fiscal considerations and constraints don’t exist. It’s certainly easier to suggest new public policies without the need to think about how those ideas might be financed. But just as my conservative futurism is science factual not fictional, the same approach must be used for governance that thinks soberly about the long term. Oh, and these CBO charts are defininitely worrisome:

Economic openness and global economic competition are at the core of the political economy that I believe will generate the sort of future that we’ll want to live in. Anytime that I can engage in a bit of myth-busting about the weakness of such a system, you know I will.

Micro Reads

▶ AI that’s smarter than humans? Americans say a firm “no thank you.” - Sigal Samuel, Vox |

▶ AI could consign educational traumas to history - Andy Haldane, FT |

▶ Google’s AI protein folder IDs structure where none seemingly existed - John Timmer, Ars Technica |

▶ Autonomous Vehicles: A Safer Road Ahead - John Bailey, AEIdeas |

▶ How to Survive the Revival of Industrial Policy - Adrian Wooldridge, Bloomberg |

▶ Google Connects A.I. Chatbot Bard to YouTube, Gmail and More Facts - Nico Grant, NYT |

▶ Silicon Valley’s quest to live forever now includes $2,500 full-body MRIs - Elizabeth Dwoskin, WaPo |

▶ DeepMind is using AI to pinpoint the causes of genetic disease - Antonio Regalado, MIT Technology Review |

▶ A Disney director tried—and failed—to use an AI Hans Zimmer to create a soundtrack - Melissa Heikkilä, MIT Technology Review |

▶ Agility’s New Factory Can Build Thousands of Humanoids a Year - Evan Ackerman, IEEE Specrum |

▶ Why We’ll Never Live in Space - Sarah Scoles, Scientific American |

▶ Telling AI model to “take a deep breath” causes math scores to soar in study - Benj Edwards, Ars Technica |

▶ On the Transition to Modern Growth - B. Ravikumar and Guillaume Vandenbroucke, St. Louis Fed |

▶ KIPP Schools and Lessons for Education Catch-up - Timothy Taylor, Conversable Economist |

▶ Super-precise CRISPR tool enters US clinical trials for the first time - Heidi Ledford, Nature News |

If a goal is set too low, that can be pernicious. That's the point.

If you're interested, you should read the UN report.

As to point 3, I believed that capitalism deserved great credit for reducing world poverty until I read this report. The statistics are fatally flawed. And, worse, it fosters false complacency. Please read this, and tell methane what you think.

https://chrgj.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Alston-Poverty-Report-FINAL.pdf