📉 Why America’s biggest bank is forecasting a bleak post-COVID economy (Is it wrong?)

Also: Orbital space junk is a disaster waiting to happen

“You should see the sun on the Ganges. It's amazing.” - astronaut Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) in Gravity.

In This Issue

Micro Reads: 2022 economy; pro-progress poetry; gig economy; and more . . .

Short Read: Orbital space junk is a disaster waiting to happen

Long Read: Why America’s biggest bank forecasts a bleak post-COVID economy (Is it wrong?)

Micro Reads

📅 2022 US Economic Outlook - Goldman Sachs | Short version: Jobless rate will head steadily lower, inflation will get worse then better, growth will get better then worse. From the report:

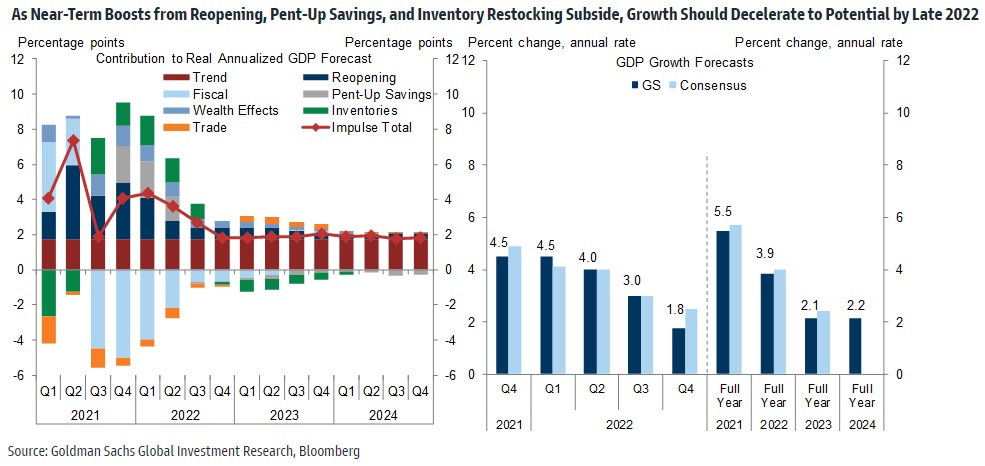

We expect the economy to reaccelerate to a 4%+ growth pace over the next few quarters as the service sector continues to reopen, consumers spend part of their pent-up savings, and inventory restocking gets underway. These forces will contend with a large and steady headwind from diminishing fiscal support that we expect will ultimately leave GDP growth near potential by late 2022. . . . The labor market should reach maximum employment by the middle of next year as red-hot demand for workers and the end of enhanced unemployment benefits bring solid job gains. We expect the unemployment rate to reach 3.7% at mid-year and 3.5% — the pre-pandemic 50-year low — by end-2022. . . . The current inflation surge will get worse this winter before it gets better, but as supply-constrained categories shift from a transitory inflationary boost to a transitory deflationary drag, we expect core PCE inflation to fall from 4.4% at end-2021 to 2.3% at end-2022.

🚗 Who Benefits from Online Gig Economy Platforms? - Christopher T. Stanton (Harvard) and Catherine Thomas (LSE), NBER | Government efforts to reclassify independent contractors as employees would create a gig economy where “buyers post fewer online jobs and fill posted jobs less often, reducing expected surplus for all market participants.”

🚂 The poetry of progress - Jason Crawford, The Roots of Progress | People were so crazy about progress during the late 19th century phase of the Industrial Revolution that they even wrote poetry about it. Among these poets of progress: Rudyard Kipling and the grandfather of Charles Darwin.

☄ Are We Really Safe From Killer Asteroids? - Adam Minter, Bloomberg | “As a start, NASA should build on DART by testing a gravity-tractor deflection spacecraft. Although it sounds extreme, preparing for a nuclear-armed mission would also make sense.”

👩💻 Best books of 2021: Technology - Financial Times | I’ve already podcasted with Azeem Azhar, author of The Exponential Age, one of the books that made the cut.

Short Read

🛰 Space junk is an orbital disaster waiting to happen

In the book Seveneves by Neal Stephenson, the Moon mysteriously cracks into seven pieces. (A tiny black hole might have been the culprit). Those giant chunks then start bumping into each other, creating lots of smaller chunks. Rinse and repeat, fragments smashing into fragments, until all those lunar pieces start raining down on Earth, superheating its atmosphere, and battering the planet.

Like any good storm, the hard rain began with a sudden thunderclap: a kilometer-wide rock that lit up eastern Europe with eerie, silent flashes as it skidded in across the upper atmosphere before digging into thick air somewhere around Odessa. Its trail set fire to dry leaves and combustible litter in the Crimea, then painted a long brushstroke of burning buildings and forests across the northeast rim of the Black Sea, ending with a long elliptical crater in the steppe between Krasnodar and Stavropol. The former city was first set on fire by radiant heat from the sky and then flattened by a blast wave. The latter got only the blast, followed by a rain of ejecta. Both disappeared from human ken.

That fictional scenario is an apocalyptic version of a dangerous orbital dynamic first proposed by NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler in 1978. In his scenario, the density of objects in low-Earth orbit becomes great enough that collisions cause a debris cascade effect, making many orbital activities far more dangerous or even impossible. The Kessler Syndrome was surely top of mind for space experts on Monday when a Russian anti-satellite missile test generated a debris field that forced International Space Station astronauts to temporarily seek shelter.

Washington said the test had generated more than 1,500 pieces of “trackable orbital debris and will likely generate hundreds of thousands of pieces of smaller orbital debris,” threatening the ISS and “other human space flight activities.” As it is, according to the Financial Times, there are an estimated 30,000 orbiting objects that are regularly tracked, “but substantially more that are too small to be followed.” Indeed, there may be a million of the latter.

Obviously there are scenarios well short of a massive, ping-ponging Kessler Syndrome that suggest we need to clean up space junk ASAP and prevent more from accumulating. And the proposed solutions have, in large part, been technological ones.

But tackling the space debris problem is at least as much an economic issue as a technological one. In the 2018 paper “Space, the Final Economic Frontier,” Matthew Weinzierl, a professor at Harvard Business School, calls it a “classic example of negative externalities [side effects whose costs are incurred by bystanders] but in a setting in which the conventional remedies suggested by economic analysis and applied on Earth have limited traction.”

You can’t, for instance, put a tax on space junk because there’s no one with the authority to collect it. There are also no clearly defined property rights in space or an easy ability to monitor and discipline harmful actions, like we just saw happen with Russia. Weinzierl: “In short, without some centralized action, space debris could generate an outcome similar to the tragedy of the commons [in which no individual charge is made for the use of a collectively owned resource.]”

So why not an international agreement, like the various nuclear agreements that began with the 1963 Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty? Again, the nature of space activities makes such agreements difficult. Again, Weinzierl:

International agreements have made some progress on the issue of space debris

by requiring that objects put into space in the future have automatic de-orbiting

capabilities, but the main provision of international treaties relevant to debris — the assignment of responsibility for debris to the party or country from which it was

first launched — has fallen far short.In fairness, identifying the origin of pieces of debris is difficult, assigning responsibility for an object having become debris (say, due to a collision with another object) is often impossible, and enforcing countries’ obligations threatens their national security and economic interests in other assets.

The analogy to global climate change, where a decades-long effort to generate international coordination has gradually confronted these obstacles, is both useful and daunting. A more encouraging analogy is to international efforts to reverse the depletion of the ozone layer, where over the several decades multiple rounds of agreements have turned the tide. Advocates of action on space debris often point to the need for public awareness of the problem, a factor often credited with encouraging swift action on the ozone layer.

If a chunk of space junk causes a space catastrophe, such as that depicted in the 2013 film Gravity, public awareness will soar, no doubt. Let’s pray that scary near-misses are enough to prompt action.

Long Read

📉 Why America’s biggest bank forecasts a bleak post-COVID economy. (Is it wrong?)

Summary: Megabank JPMorgan sees little reason to think the post-pandemic economy will grow faster than the so-so, pre-pandemic one. If anything, the risk is to the downside. Trends in labor force growth, business investment, and worker skills are uninspiring. And emerging technologies like AI and robotics, assuming they really have lots of potential to boost worker productivity, will need lots of complementary business investments to realize that potential. And that doesn’t seem to be happening.

Over the past two years, economic forecasting has been COVID-19 forecasting. When the pandemic faded enough to allow a broad economic reopening, the economy was sure to boom. With so much pent-up demand and unusually high savings, the only real question was whether the economy would be hot, red hot, or crazy red hot. From Wall Street to Washington, economists have been forecasting rapid GDP growth this year, somewhat slower next, and then a big deceleration back to “trend” growth in 2024 and beyond. (And these forecasts have typically assumed passage of the Biden agenda.)

For example: Goldman Sachs is currently expecting real GDP growth of 5.5 percent this year, 3.9 percent in 2022, and then an average of 2.2 percent in 2023 through 2025. That might seem pretty robust, but many forecasts used to be even growthier. The Delta variant and global supply chain bottlenecks have prompted an overall downshift in 2021 forecasts from last summer. One can see the old hyper-optimism in the most recent Congressional Budget Office forecast, published this past July. Back then, the CBO was looking for 7.4 percent growth in 2021, 3.1 percent in 2022 — but then a big slowdown: 1.1 percent in 2023, 1.2 percent in 2024 and 2025, and 1.6 percent in the following five years.

Now that 1.6 percent number is what the CBO sees as potential, or trend, GDP growth. Think of it as the sustainable rate of growth where things like unemployment and industrial capacity utilization are steady. Although booms and busts will happen, it’s this long-term trend growth rate that determines long-run growth and prosperity. And by historical standards 1.6 percent is pretty low, only about half the post-World War II pace and a third lower than the growth rate since 1990.

In a new report, JPMorgan’s economics team notes that before the pandemic, its estimate of potential GDP growth stood at a “rather subdued” 1.5 percent annually. And how about now? Certainly a lot happened over the past nearly two years to cause a re-evaluation. That includes pandemic-related phenomena such as “work from home,” increased ecommerce, as well further advances in AI and robotics. Then there are the exciting emerging technologies in biology, energy, and space. So when considering all that, what’s the new JPMorgan estimate? Here you go (bold by me):

While the dust has not fully settled, the early picture that is emerging on post-pandemic potential GDP growth suggests that trend growth remains stuck in the slow lane. While we are staying with our prior estimate of 1.5%, the risks look tilted to the downside. The pandemic-related increases in efficiency (of which there appear to be many) have more likely shifted up the level of productivity, rather than increased trend productivity growth. Moreover, an increase in trend labor productivity growth is needed just to offset the slowing trend in labor supply growth. Since our last update, trend growth in effective labor supply has stepped down 0.3%-pt to just 0.1% per year. To achieve 1.5% trend growth requires total economy productivity growth of 1.4%, or nonfarm business productivity growth of 1.9% — a pace barely eclipsed in the very high productivity growth 1990s expansion.

(Interregnum: Keep in mind that the drivers of economic growth are (a) the growth of labor supply/hours worked and (b) the growth in worker productivity/output per hours worked. Because the first is so heavily influenced by long-term demographic trends, it’s easier to forecast. Productivity is more of a wild card.)

OK, so kind of a bummer, especially for loyal Faster, Please! readers. But let’s stay centered and dig into the reasons for the bank’s pessimism.

First, growth in the working-age population, those 16 to 64, has been disappointing. It’s currently about 2.5 million below pre-pandemic Census Bureau expectations. Part of the reason is health related: COVID-19 and overdose deaths.

But the most important factor is “the vast majority of the shortfall in working-age population growth appears driven by a decline in immigration to the United States, beginning during the Trump administration and continuing through the COVID pandemic.” The bank notes that immigration over the past three years has been about 2.1 million below what would have occurred if pre-2017 trends in annual inflows had continued. Extrapolating the data into 2021, “we estimate that the US population is missing about 3 million recent immigrants relative to pre-2017 trends, a large majority of whom would have been of working age.”

Looking forward, JPM is pessimistic around the rate of potential labor force growth, given the aging of the resident US population, how the pandemic accelerated retirements, and its expectation that any rebound in immigration is likely to be, at best, a “slow process.”

Second, with such weak growth in the labor force — maybe just 0.1 percent annually — generating overall fast economic growth will require a vastly more productive economy. If not many more workers, then each worker needs to generate a lot more output. That really didn’t happen after the Global Financial Crisis and Great Recession, which is why we got the slow growth “new normal” economy. JPM: “Productivity in the nonfarm business sector expanded at only a 1.1% annual pace, half the 2.2% rate seen in the 1990s expansion.”

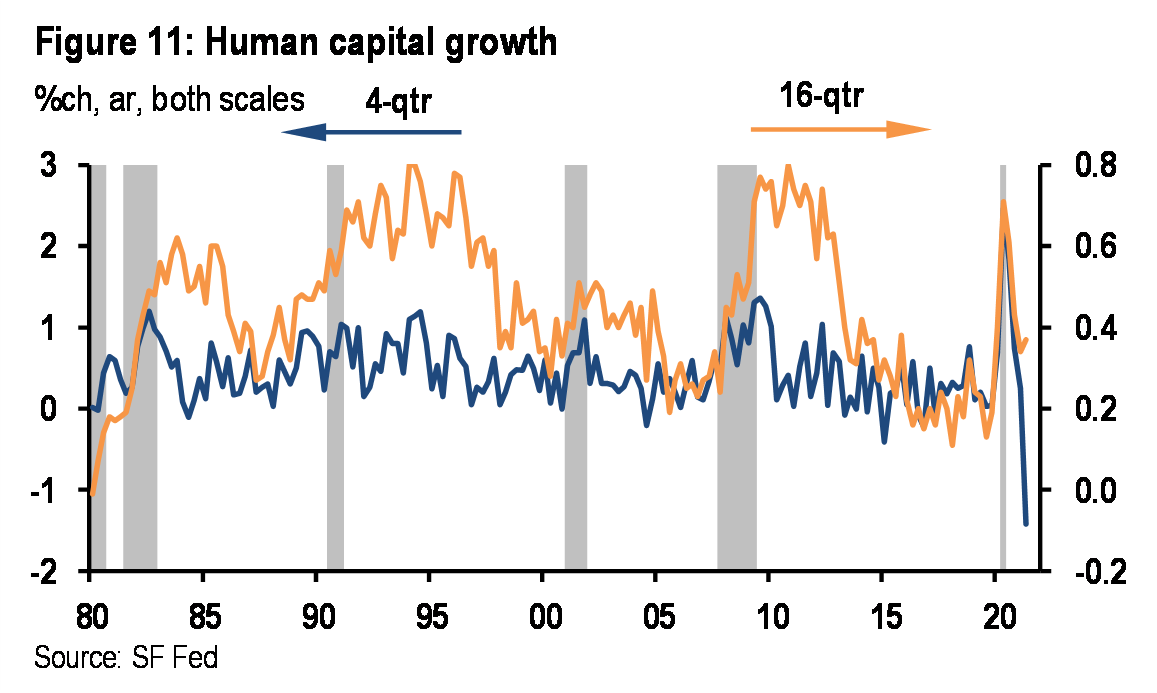

Will productivity growth be faster during this expansion? Pre-pandemic trends in both business investment (which would give workers more machines) and human capital investment (giving workers more skills through education and training) give JPM little reason for optimism. Nor does it think the pro-productivity aspects of the pandemic, particularly work-from-home, will result in a sustained productivity boost. JPM notes that that “the industries with the greatest use of WFH arrangements are finance and professional & business services. The industry-level productivity data released so far do not point to these industries leading the way since the pandemic.”

If workers gaining more physical and human capital won’t kick productivity into overdrive, then maybe technological progress and innovation will. The common measure of that is total factor productivity, or productivity not accounted for by those two previously mentioned factors of physical and human capital. Again, the recent trend isn’t encouraging. JPM: “After a brief pop toward the end of the last expansion, TFP growth (adjusted for utilization) during and since the pandemic appears to have returned to the slow pace that prevailed during most of the last expansion.”

But what about all the cool science and tech advances you’ve been reading about, including in Faster, Please!? Again, JPM (bold by me):

This dive into the economic drivers of productivity — capital deepening, skills growth, etc. — will likely appear somewhat divorced from discussions that focus on specific technological stories, such as AI, robotics, or autonomous vehicles. There are a few reasons why economists tend to focus on the former set of drivers. For one, many of these technologies have been around for a while. For example, robots were first used in auto production in the US in 1961. Predicting when these technologies will become commercially viable is tricky; predictions of the commercial roll-out of fully autonomous vehicles have been notoriously unreliable. But in almost all cases making a technology economically viable requires investment, not only in R&D but also in the new equipment that usually embodies the newer vintages of technology. Productivity booms tend to coincide with investment booms. Until business investment steps up more meaningfully, the odds remain low that productivity growth will shift higher.

A few additional thoughts here:

The JPM econ team has, over the years, been notably cautious about forecasting any sort of innovation-driven productivity boom. So this doesn’t surprise me. And so far, to be fair, their caution has been proven correct.

JPM is also correct in its view that for technological advances to translate into private sector productivity growth there needs to be complementary investments. For example: It took decades for complementary innovations to happen so that electrification and computers could be effectively integrated into business. As economist Erik Brynjolfsson told me back in early 2020: “It’s not that the technology is unimpressive. It’s that we aren’t translating them. . . . It just takes time for companies to reinvent their business processes, their organizations, and the way they do business. That is something we need to work on. The bottleneck is in there, not in the core technologies. . . . Those are as fundamental as anything we’ve ever seen — maybe more fundamental in terms of the breakthroughs.”

Finally, and this is my repetitive refrain, policymakers should assume the pessimists and skeptics are correct. Pro-growth policies should be a priority. Certainly, the one that screams in the JPM report is the need to boost immigration. It’s pretty tough to call yourself “pro-economic growth” if you want to restrict the strivers and the talented from coming to America.