🔮 Life in 2050, as seen by 'deep tech' venture capitalists

Also: The failure of Soviet Russia has lessons for America today

“In the annals of innovation, new ideas are only part of the equation. Execution is just as important.” - Steve Jobs

In This Issue

Micro Reads: Omicron economics, nuclear energy, basic science, and more . . .

Short Read: Life in 2050, as seen by “deep tech” venture capitalists

Long Read: The failure of Soviet Russia has lessons for America today

Micro Reads

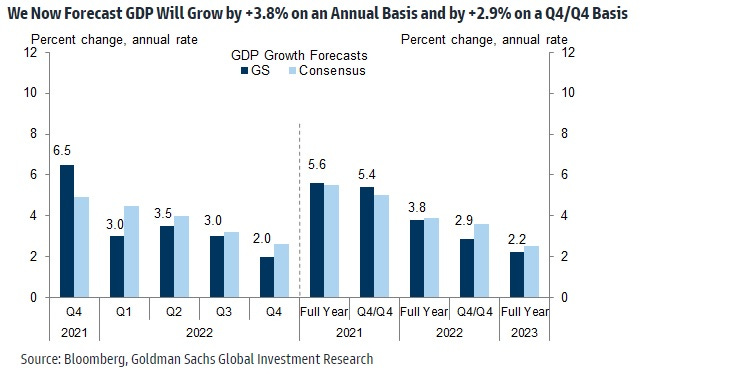

🦠 Updating Our Outlook to Incorporate Omicron - Goldman Sachs |

First, Omicron could slow economic reopening, but we expect only a modest drag on service spending because domestic virus-control policy and economic activity have become significantly less sensitive to virus spread. . . . Second, Omicron could exacerbate goods supply shortages if virus spread in other countries necessitates tight restrictions. This was a major problem during the Delta wave, but increases in vaccination rates in foreign trade partners since then should limit the scope for severe supply disruptions. . . . Third, Omicron could delay the timeline for some people feeling comfortable returning to work and cause worker shortages to linger somewhat longer. We have updated our GDP forecasts to incorporate our updated virus outlook as well as the latest GDP tracking data. . . . We now expect GDP growth of +6.5%/+3.0%/+3.5%/+3.0%/+2.0% in 2021Q4-2022Q4. This implies 2022 GDP growth of +3.8% (vs. 4.2% previously) on a full-year basis and +2.9% (vs. +3.3% previously) on a Q4/Q4 basis.

🤖 Japan's shrinking labor pool sharpens quest for productivity - Nikkei Asia | “The growing demographic skew toward seniors casts a shadow over Japan's economic outlook for the coming years. Companies are turning to technology and other avenues to cope with a labor shortage poised to worsen.” Given the country’s aging population, continued economic growth in Japan will have to rely on technology-driven productivity gains, but red tape could slow the spread of automation and artificial intelligence in its economy.

⚛ The New Nuclear Moment - Robert Zubrin, National Review | Support for nuclear power has been growing on the left. France has reversed its shift away from nuclear in the hope of reaching carbon neutrality by 2050, and many others in Europe are following suit. In the US, Democrats are waking up to the tension between environmentalists in the party and blue-collar voters: “The party was not about to abandon its core belief that carbon emissions present an existential threat to humanity, so changing its position on coal mining or fracking was out. But nuclear power is carbon-free.”

🧪 Why Basic Science Matters for Economic Growth- IMFBlog| When it comes to boosting long-term economic growth, funding for R&D is a critical investment for the future. “An implementable hybrid policy that doubles subsidies to private research (basic and applied alike) and boosts public research expenditure by a third could increase productivity growth in advanced economies by 0.2 percentage point a year.” And because basic research produces positive externalities not captured by private companies, the authors write, governments should especially support basic science.

Short Read

🔮 Life in 2050, as seen by “deep tech” venture capitalists

“Line go up” is a bit of Twitter meme mockery directed toward people who prefer it, well, when the line goes up! Maybe that line represents the S&P 500, maybe it represents real GDP growth. As regards the latter, proponents of the notion that the West is living in “late-stage capitalism” use “line go up” as a way of saying that economic growth is irrelevant. Its benefits only go to the rich, while the rest of us struggle through a dystopia of inequality.

Yet economic growth powered by technological progress and higher innovation-driven productivity will be as valuable going forward as it has been in the past. We have a lot of problems to solve, and having more and better resources to solve them is essential. That said, it’s always helpful to have a positive image of the future toward which to strive. What, for instance, might growth and progress bring us by the year 2050?

One possible answer comes from Prime Movers Lab, a venture capital firm that focuses on “breakthrough scientific startups . . . reinventing energy, transportation, infrastructure, manufacturing, human augmentation, and agriculture.” It’s put together a roadmap of sorts about how the next three decades might play out if the line keeps going up:

Energy. “By 2050, humanity will have the technology it needs to halt all or virtually all carbon emissions from energy while ending energy poverty. Policy choices and the conviction of consumers, citizens, and businesses will be required in order to deploy these technologies at the speed needed.” Examples: first commercial nuclear fusion power plant in the 2030s, direct air capture of CO2 below $100 a ton by 2040, battery energy density 5x that of 2020 by 2050.

Infrastructure. “By 2050, we’ll have the tools to provide us better, more efficient, and healthier buildings; to produce abundant, clean water for billions; to move the clean energy humanity will be generating to where it’s needed; and to augment the information exchange and collaboration that drive human innovation and discovery.” Examples: cheap, efficient desalination by the 2030s; floating cities & towns emerge in the 2040s, wireless bandwidth increases to 90,000 Gbps per device by 2050.

Transportation. “By 2050, new technologies will give us the tools to revolutionize transportation. Advances in autonomy will make transportation cheaper, safer, cleaner, and easier than ever before for goods to reach people around the world, and for humans to connect with one another.” Examples: commercial hypersonic aviation in the 2030s, near-Earth asteroid mining in the 2040s, lunar helium-3 mining for fusion energy by 2050.

Manufacturing. “By 2050, we’ll have the tools to manufacture better products to satisfy the physical needs of billions, while doing so at lower cost, in a more distributed fashion, with less human labor, and a lower environmental footprint.” Examples: robots automate construction in the 2030s, domestic robots become commonplace by 2040, optical computers by 2050.

Human augmentation. “By 2050, humanity will have better tools than ever before to improve human health, overcome disease and disability, address the ravages and causes of human aging, and fundamentally improve human cognition and human mental well-being.” Examples: brain repair and reversal of neurodegenerative diseases in the 2030s, lab-grown organs replace organ donation by 2040, slowing and partial reversal of human aging by 2050.

Agriculture. “By 2050, scientific breakthroughs will have given us the tools to dramatically increase our food production while sparing land, forests, water, and animal suffering. Global food demand will still be rising, and the transition to sustainable food production will not be complete, but our tools will be better than ever before and offer us the possibility — if we choose it — to begin to restore nature, even as we increase access to safe, healthy, and nutritious food to levels never before seen in human history.” Examples: self-fertilizing crops reduce the need for synthetic fertilizer in the 2030s, next-generation crops for higher yield in the 2040s, genetic technologies restore lost species and ecosystems by 2050.

And, yes, the roadmap does contain links to all those possible advances and many more. Now, not all of them may happen on this exact timeline — or at all. Then again, there might be others that happen more quickly, and still others that we’re not even thinking about right now. If the dystopians and de-growthers can paint dire futures based on imprecise computer modeling — if even that — then certainly optimists can present a more uplifting vision of tomorrow based on technologies that companies are currently working on. As futurist Frederik Polak wrote decades ago, “Any culture which finds itself in the condition of our present culture, turning aside from its own heritage of positive visions of the future, or actively at work in changing these positive visions into negative ones, has no future.”

Long Read

📉 The failure of Soviet Russia has lessons for America today

Please keep in mind, for a few moments, this recent Twitter exchange between a venture capitalist and a US senator:

The Soviet Union was economically inefficient — but, on the other hand, it was able to cause massive human suffering and death. Those, basically, are the findings from a burst of Russia scholarship over the past decade or so, which has added considerable detail to a fairly obvious conclusion. Much of this research is reviewed in the new paper “New Russian Economic History” by Ekaterina Zhuravskay (Paris School of Economics), Sergei Guriev (Sciences Po), and Andrei Markevich (New Economic School), or ZGM from here forward. (Thanks to Branko Milanovic for the pointer.)

Let’s start with the economics:

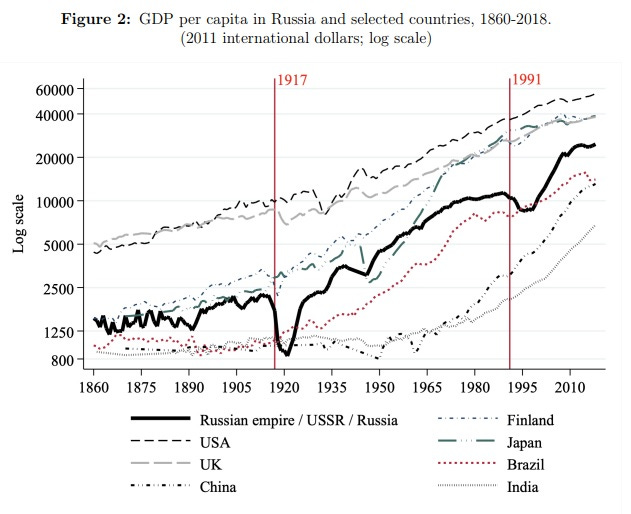

Overall, the new data confirm the Russian Empire’s relative economic backwardness. They also show that the Russian revolution was an economic disaster. The new studies also help documenting that, despite the acceleration of the Soviet economy during the Big Push industrialization, the gap with the advanced economies had remained large, and it increased over time as the Soviet economy slowed down. The recent research also shows that even during the period of the intensified growth of the Stalin’s industrialization, the Soviet Union did not outperform the counterfactuals based on the extrapolation of the Tsarist trends under various reasonable scenarios.

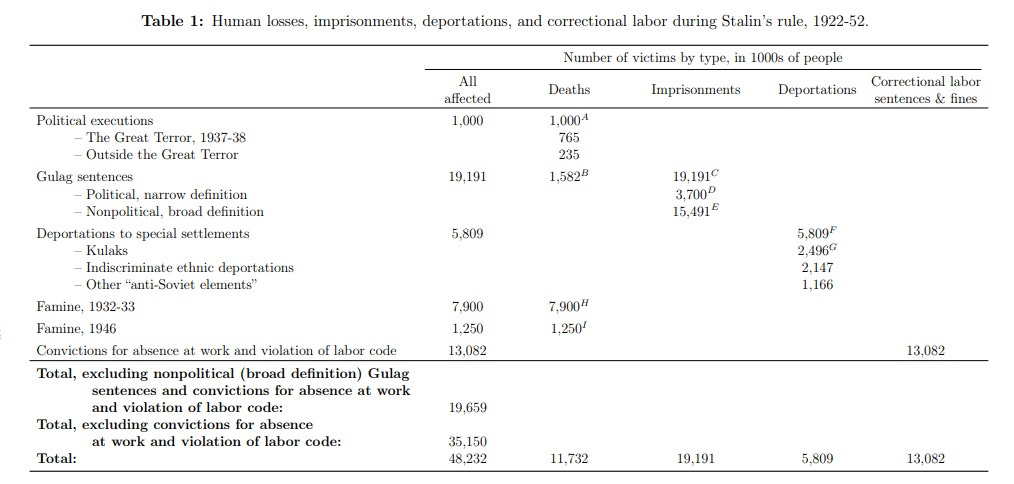

And I think this graphic sums up the human cost of Communism:

ZGM: “Overall, during the Stalin’s rule, about 19.7 million people became the victims of political executions, political imprisonments, deportations, and famines. Another 15.5 million were convicted to Gulag on criminal charges and another 13 million were subjected to forced correctional labor and fines on the charges of violating the labor code.”

I’m writing about this paper for two reasons. First, it’s always good to remind ourselves of the comprehensive and deep failure, along all human dimensions, of this great socialist experiment. There was no silver lining to that suffering, such a rapid industrialization. Again, from the paper: “Stalin’s industrialization did not do better economically than the extrapolation of the imperial trend or comparator market economies, despite the industrialization’s enormous human costs.”

Second, the paper helps provide comparative lessons for other nations on the factors important for creating a flourishing and prosperous society. It helpfully references the work of science historian Loren Graham of both MIT and Harvard. In Graham’s 2013 book, Lonely Ideas: Can Russia Compete?, he investigates Russia’s long history of backwardness despite an equally long history of creativity, and not just in the arts. The Russians are an inventive people with numerous technological firsts, Graham notes, from transmitting radio waves before Guglielmo Marconi to pioneering the development of transistors and diodes to building the first electronic computer in continental Europe. Space and nuclear, too. And yet, the historian asks, “Where is the Russian Thomas Edison, Bill Gates, or Steve Jobs? Actually, they exist, but you have never heard of them because they fell flat on their faces when they tried to commercialize their inventions in Russia.” Invention must lead to diffused innovation for an economy to advance. And there are things societies do that both help and hinder that advance. Graham:

The person who develops an idea with commercial potential needs a variety of sustaining societal factors if he or she is to be successful. These factors are attitudinal, economic, legal, organizational, and political. Society needs to value inventiveness and practicality; the economic system needs to provide investment opportunities; the legal system must protect intellectual property and reward inventors; and the political system must not fear technological innovations or successful businesspeople but promote them. Stifling bureaucracies and corruption need to be restrained. Many people in Western societies and, increasingly, Asian ones take these requirements for granted. Just how difficult sometimes they are to fulfill is illustrated by Russian history and by Russia today.

And while the above problems, at minimum, intensified during the Soviet era, they predate Communism and linger on today. But I want to focus on just one for the remainder of this essay, the bit about embracing entrepreneurs and businesspeople. Graham notes that from 2005 through 2013, he visited dozens of universities and research institutes across Russia, all the while comparing the attitudes of engineers, students, and scientists there to those at MIT. Back home, he frequently heard science and engineering students talk about being the next Bill Gates or Steve Jobs, or at least starting a company, selling for a high price, and then starting a new one.

Graham: “I can truthfully say I have never heard such an answer from a Russian student. Russian students — and working scientists and engineers — just do not think that way.” He goes on to cite a 2010 survey of Russian scientists and engineers on their attitudes toward their work. These two responses were hardly atypical:

There are no models in the consciousness of [Russian] people of a successful scientist-entrepreneur. We look upon a scientist as a disinterested person who does everything for the good of humankind. An entrepreneur is a member of the bourgeoisie who takes advantage of other people.

We do not have an innovation culture — no experience, no traditions. Our scientists, they are all still Soviet in their attitudes, for them business is something dirty. Our scientific culture is practically untouched by the business entrepreneurial spirit.

As Graham goes on to explain, this anti-business attitude predates the Soviet Union, though the Communist experience may have hardened it. Graham:

In the nineteenth century, throughout the Soviet period, and still today, biznes, or “business,” has often been seen by Russians as a disreputable activity. Intellectuals (intelligenty) in particular saw (and often still see) commerce as below their dignity. In recent post-Soviet years the connection of successful businesspeople, especially the oligarchs, with corruption has only deepened suspicion of business operations.”

All of which might sound familiar to readers familiar with the work of economist Deirdre McCloskey. She argues that the key to the Scientific Revolution creating an Industrial Revolution was a change in attitude about commercial life. Western European society came to accept the value of disruptive innovation and entrepreneurship, or at least stopped trying to block it. Society accepted what McCloskey calls the “Bourgeois Deal,” which she describes this way:

Allow me, in the first act, to have a go at innovating in how people travel or buy groceries or do open‐heart surgery, and allow me to reap the rewards from my commercial venturing, or absorb the losses (darn it: isn’t there something the government can do about that?). I agree, reluctantly, to accept that in the second and third acts my supernormal profits will dissipate, because my lovely successes from innovating the department store or devising the laptop will attract imitators and competitors. (Those pesky imitators and competitors. Hmm. Maybe I can get the government to stop my competition.) By the end of the third act, I will have gotten rich, thank you very much, but only by making you, the customers, very rich indeed.

Russia has never accepted this deal. The same goes for some in the United States, specifically those “billionaires are a policy error” folks. Rather than just criticizing uberbillionaire entrepreneurs for this or that business practice, they attack them for their wealth — even though most of the value they create goes to us, not them. If the efforts of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos play a huge role in creating a Green Economy here on Earth and a Space Economy above it, is their wealth really the main issue? Or if the backers of nuclear fusion turn into the next wave of mega-wealthy?

Now, maybe China will create its own deal. Graham concedes that its rise is “the greatest challenge to the basic thesis of this book, that technology is most creative and successful in a democratic, law-governed society.” But I’ll take my chances with an America that sticks with the Bourgeois Deal of allowing and rewarding disruptive entrepreneurship (along with great government funding of science).