🧐 Imagine an America with steep billionaire taxes — and without Amazon, Pixar, SpaceX, and Tesla

Also: 5 Quick Questions for … Brookings Institution scholar Mark Muro on the changing geography of tech

Welcome! This is a free-for-everyone issue of Faster, Please! For paid subscribers: Twice a week, I write a long essay on growth/innovation/culture, collect the most interesting news and most insightful analysis on the subjects, and offer orginal short/sharp interviews with interesting thinkers.

But every subscriber, free and paid, receives a weekly “best of” issue, typically on Saturdays. This includes brief summaries of my twice-weekly essays, my favorite answers from 5 Quick Questions Q&As, and selected “micro reads.” (There will also be the occasional paywall-down issue like this one.)

In This Issue

The Essay: 🧐 Imagine an America with steep billionaire taxes — and without Amazon, Pixar, SpaceX, and Tesla

5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for … Brookings Institution scholar Mark Muro on the geography of tech

Micro Reads: humanity’s vast future, America’s green energy moment, the flywheel of progress, and more …

Nano Reads

Quote of the Issue

"The Earth is finite, and if the world economy and population is to keep expanding, space is the only way to go." - Jeff Bezos, 1982 high school valedictorian speech.

The Essay

🧐 Imagine an America with steep billionaire taxes — and without Amazon, Pixar, SpaceX, and Tesla

Item: President Joe Biden will propose a minimum 20% tax rate that would hit both the income and unrealized capital gains of U.S. households worth more than $100 million as part of his budget proposal to be released on Monday. … The administration projects that more than half of revenues for the new payment would come from the nation’s roughly 700 billionaires. (Bloomberg, March 26, 2022)

Two reasonable questions to ask about any public policy idea: First, what problem is the idea meant to solve or ameliorate? Second, what are the trade-offs? (Getting one thing typically means giving up another.) And the answers to both those questions make me queasy about ongoing efforts to “capture” more of the income and wealth of America’s richest people, especially those who got that way by starting and building great companies.

Talking (wealth and income) taxes

Let’s start with that first question. Whether we’re talking about Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax from her 2020 presidential campaign or President Joe Biden’s new billionaire tax, the main problems that these plans are supposedly attempting to address are revenue generation and tax fairness. To be sure, those are issues about which I’m also concerned. But I think it’s a mistake to not be equally concerned — perhaps even more so — about how the current tax code encourages or discourages productive economic activity. Likewise, we must consider how changes in tax policy affect business innovation and investment.

Which brings us to the second question: Might these efforts to raise revenue and reduce inequality generate wholly undesirable trade-offs and numerous unintended consequences — especially when it comes to business innovation and economy-wide productivity growth? After all, the reason I write this newsletter is because of my deep concern about decades of lagging science progress, technology invention, and business innovation.

The Elon Musk entrepreneurial empire: a case study

I think my concerns are reasonable. Take the case of the Biden administration’s version of "He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named" — or named only rarely — Elon Musk. Remember, he’s not just an uberbillionaire with dodgy Twitter behavior. He's also an immigrant who both resurrected the American space industry and grew an electric auto company that makes him, as his Time magazine Person of the Year profile puts it, “arguably the biggest private contributor to the fight against climate change.”

But would SpaceX and Tesla — combined value of an estimated $1.2 trillion — exist in a world of sharply higher investment taxes and a fat new levy on wealth? Maybe not. At least not both of them.

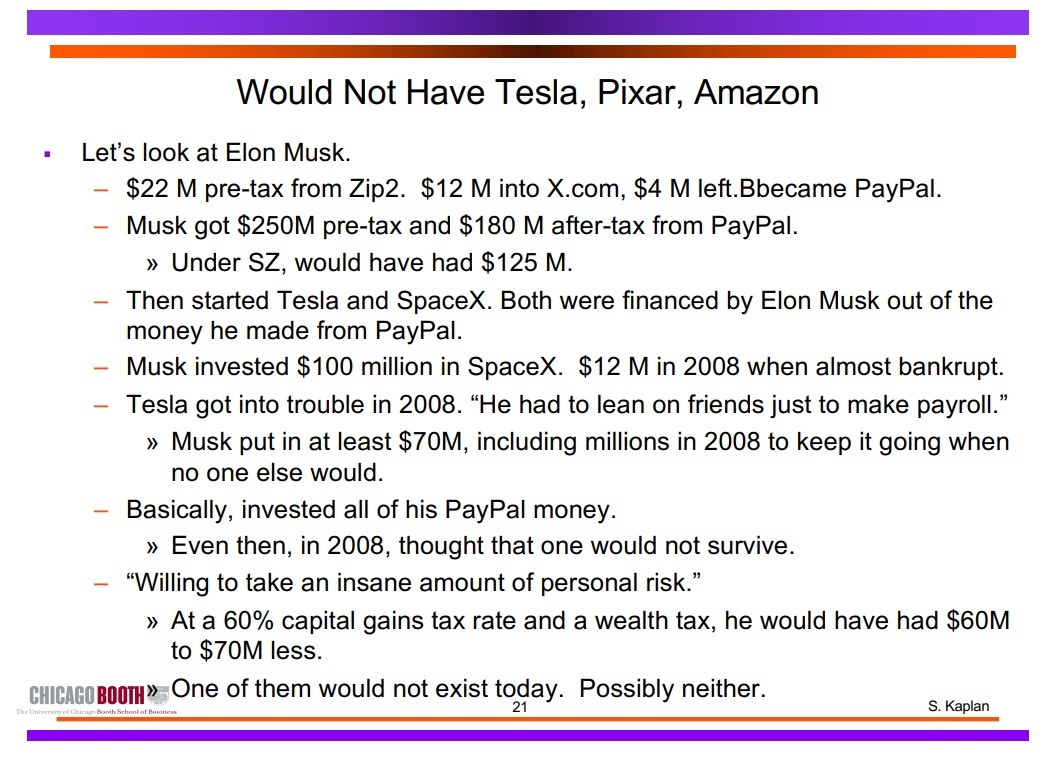

University of Chicago economist Steven Kaplan has run the numbers. To begin: Musk was one of the “PayPal Mafia,” the founders and early employees of the financial technology company. When PayPal was bought by eBay in 2002, Musk, the largest shareholder, walked away with $250 million before taxes, leaving him with $180 million after taxes.

What did Musk do with that cash? Well, he didn’t buy some monstrous Bel-Air mansion or pricey Picasso painting. Instead, he started SpaceX in 2002, putting in $100 million, and Tesla in 2003, putting in $80 million. Musk: “I thought the probability of success was so low that I provided all of the money. All of the money just came from me personally. I didn't want to ask people, other investors for money if I thought we were going to die because I thought we were.”

Of course, it’s hardly been a smooth ride getting from there to here. In 2008, during the Global Financial Crisis, both companies almost went bankrupt. Musk calls it “definitely the worst year of my life.” Tesla closed a financing round on Christmas Eve 2008. “It was the last hour of the last day that it was possible,” he recalled in 2015. “Even then, we only narrowly survived.”

As for SpaceX, here’s a bit from a December 2021 podcast chat I had with Eric Berger, senior space editor at Ars Technica and the author of Liftoff: Elon Musk and the Desperate Early Days That Launched SpaceX:

By far, the most desperate moment for SpaceX was after the third flight of the Falcon 1 rocket where pretty much everyone assumed they were going to be successful. They were already running out of money. And then that rocket went up and failed. That was the summer when Elon Musk was getting divorced, where Tesla was hemorrhaging money. And now SpaceX had just failed for the third time. [SpaceX President] Gwynne Shotwell said they had payroll for maybe six or eight more weeks, then the company was going to go bust.

And so that was a desperate period when they were leading up to the launch and they had one more rocket, the fourth rocket they were going to launch, and they were flying it out to [the Kwajalein Atoll launch site in the Marshall Islands]. ... And as they were flying that first stage toward Kwajalein, it starts imploding on the C-17 aircraft. And so this was their last piece of hardware. So that was probably the most desperate moment when everyone on that plane thought they might die due to that imploding rocket. And then they were also concerned about losing the hardware. They were able, obviously, to salvage it.

Indeed, they did. That historic fourth flight on September 28, 2008 made the Falcon 1 the first privately built liquid-fueled booster to reach orbit. It saved the company. But would that launch have happened if Musk had left PayPal with $60 million less? Would Tesla have muddled into 2009 and beyond? Kaplan doesn’t think so. “Either SpaceX or Tesla would not exist — and I don’t think anyone else would have done it,” he said in a 2020 debate with University of California, Berkeley, economist Emmanuel Saez, a wealth tax proponent.

Interregnum: Kaplan’s analysis here is of a plan by Saez and Gabriel Zucman that was the basis of the Warren wealth tax. I would note, however, that the Biden plan is also a significant tax, estimated to raise some $360 billion over a decade. It might also require some wealthy entrepreneurs to sell lots of stock. As The Washington Post explains: “The White House tax plan would dramatically change what some of the wealthiest Americans pay in taxes. Tesla chief executive Elon Musk would pay an additional $50 billion, while Amazon founder Jeff Bezos would pay an additional $35 billion, according to calculations by Zucman, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley.”

Update: Elon agrees:

No Amazon Prime, no Woody and Buzz

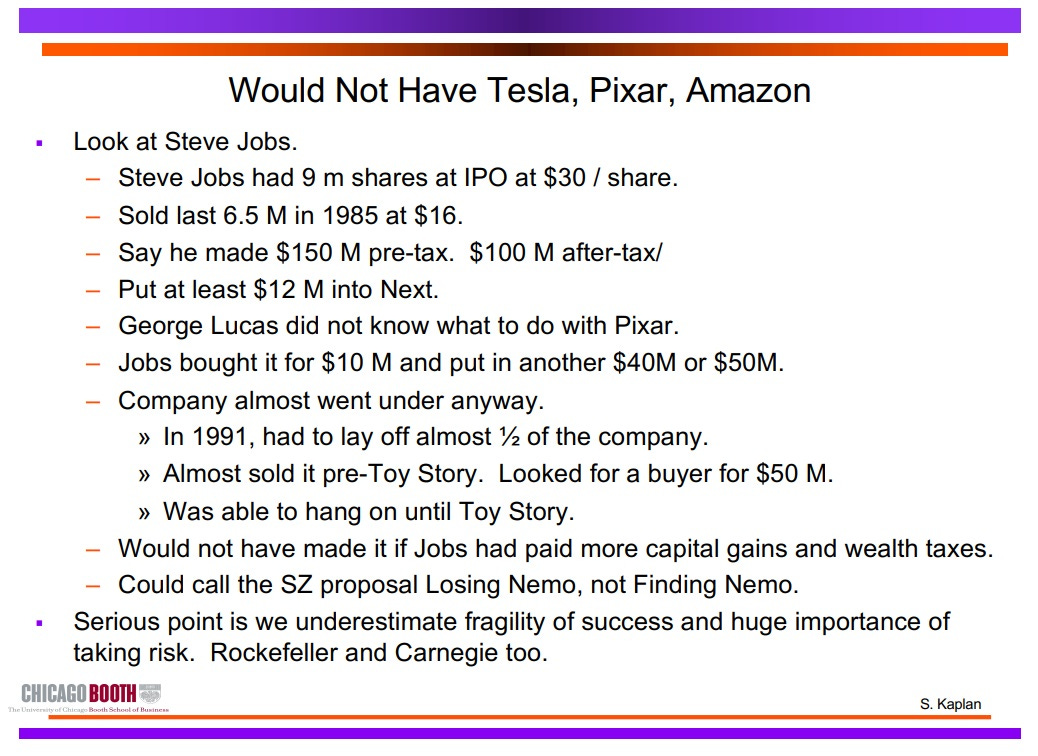

What’s more, much the same case can be made for Amazon and Pixar as for Tesla/SpaceX. Kaplan:

Steve Jobs got his money from Apple, he left Apple, and he put a big chunk of it into Pixar. It also almost went bankrupt, it didn’t, and if you had taxed him more, he would have had to have sold Pixar. It wouldn’t have been Pixar. So you know what I would say there is that you would have “Losing Nemo” instead of “Finding Nemo.”

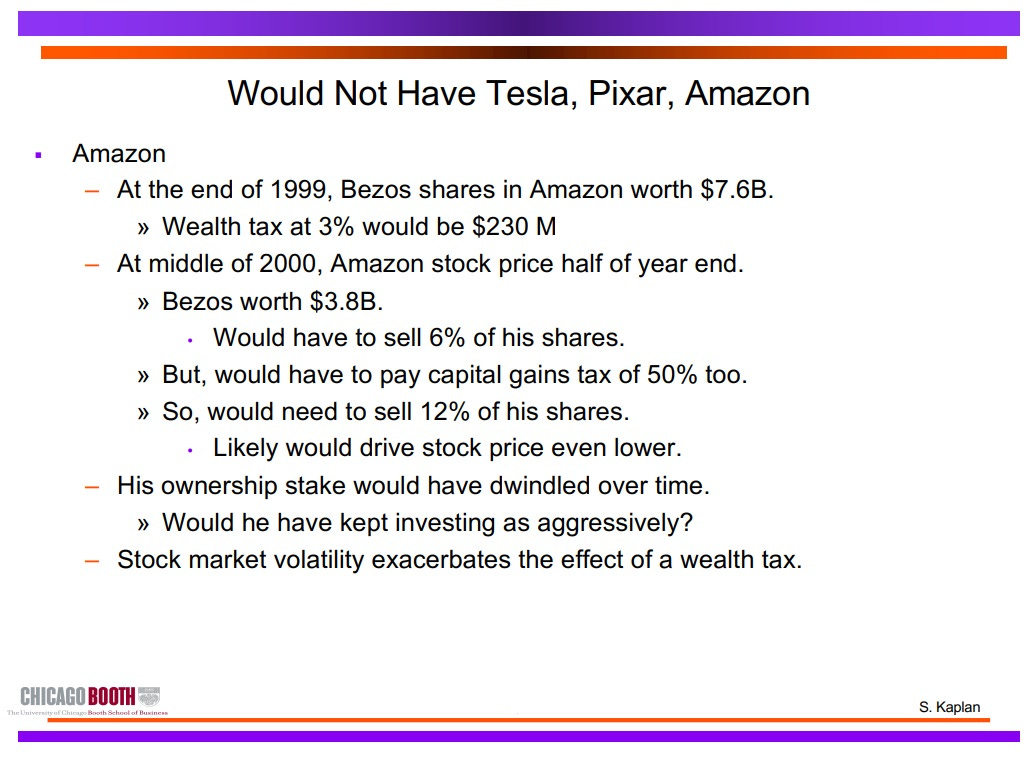

Jeff Bezos was worth $4.7 billion or $5 billion in 2000. At the peak of the dotcom bubble, Amazon hadn’t really succeeded then. And if you imposed a 5 percent wealth tax on him when it was 5 billion, that’s a $250 million tax. By the time he would probably get around to paying it, which would be June [of 2000], his shares were worth 2.5 billion [due to the plunging stock market]. So now he’s got to sell. To get the 250 million – he would have to sell 10 percent of his shares. But then we [also] have a 50 percent capital gains tax. Got to sell 20 percent of [the] shares. So in six months, under this plan, he would have to sell 20 percent of Amazon in that situation. Which would probably – what would that do to the stock price? Probably drive it down further. So maybe 25 percent of Amazon. Do you want Jeff Bezos to be selling 25% of Amazon? In 2000?

No such a thing as a free lunch or free Amazon Prime

So, trade-offs. And if you are a labor activist who doesn’t like Amazon, an astronomer who doesn’t like SpaceX and all the satellites it puts in the night sky, or an old-school cartoon buff who loves the traditional 2-D animation that Pixar killed, maybe a world without those companies is a better world. That lunch is a great bargain!

As for me, however, I like a world that includes those companies and the valuable products and services (and toons) they provide. But understanding the potential trade-offs is necessary no matter where one stands.

And for my readers who might like to still sock it to the billionaires, one final point: According to estimates by Nobel laureate economist William Nordhaus, innovators captured only 2 percent of the value they created between 1948 and 2001. He found that “only a miniscule fraction of the social returns from technological advances” accrued to innovators and concluded that “most of the benefits of technological change are passed on to consumers.” I would guess an update analysis would be similar. Indeed, I wrote last April about how most of the value created by Bezos and Amazon doesn’t go to Bezos.

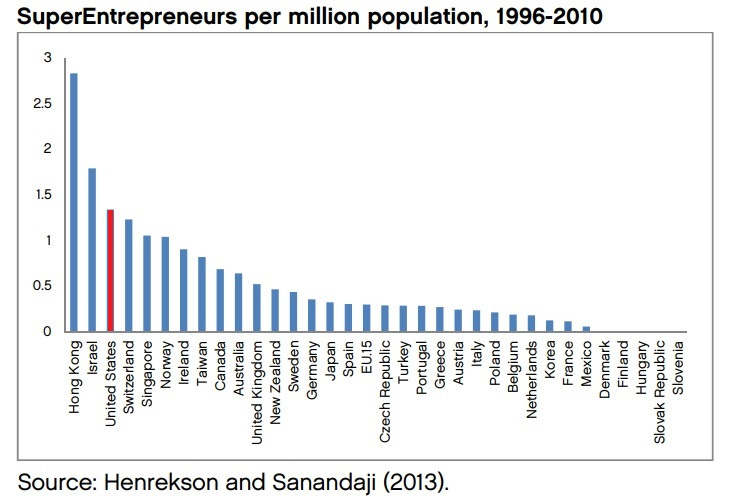

A 2019 Economist piece speculated that an understanding of Nordhaus’s point is why “billionaires are tolerated even by countries with impeccable social-democratic credentials: Sweden and Norway have more billionaires per person than America does.” If only more American policymakers possessed similar insight.

5QQ

❓❓❓❓❓ 5 Quick Questions for … Brookings Institution scholar Mark Muro on the geography of tech

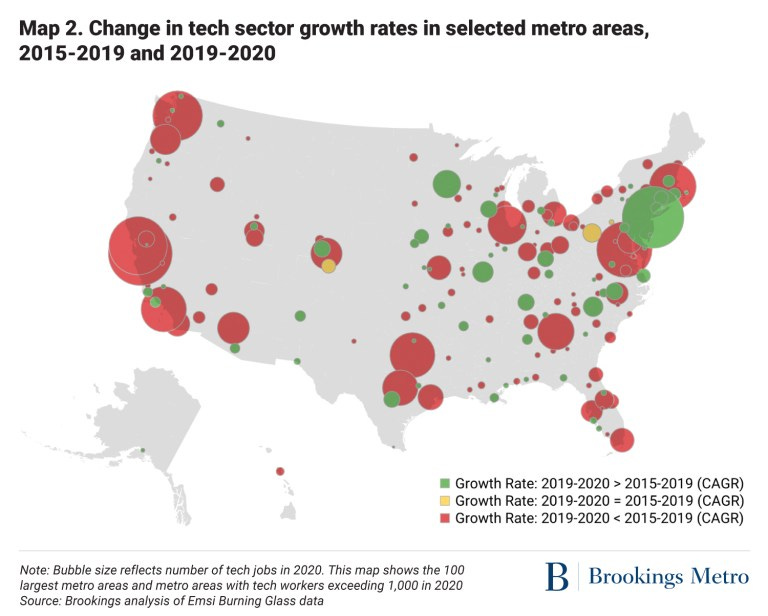

Mark Muro is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, a think tank in Washington, DC, and the policy director of Brookings Metro. Muro and Yang You recently authored “Superstars, rising stars, and the rest: Pandemic trends and shifts in the geography of tech” for Brookings.

1/ How has the geographic distribution of the tech sector changed since the outbreak of COVID-19 versus pre-pandemic?

One thing that’s interesting, first, is what’s NOT changed. Contrary to hot takes promising they would become ghost towns, tech’s big coastal superstars — places like San Francisco, Seattle, and New York — aren’t going anywhere. They in fact slightly increased their share of the national sector.

But beyond that, numerous new and different places have seen upticks in tech employment growth. One group of growers has been what we call the “rising stars” — dynamic up-and-coming metro areas like Atlanta, Dallas, Denver, Orlando. These often Sun Belt places have been adding tech jobs rapidly. Likewise, we see dozens of smaller quality-of-life meccas and college towns that saw their tech employment accelerate in the pandemic. It may be right to call these “Zoom towns” given that remote work has likely supported their growth.

2/ Do you think the pandemic change in tech geography is temporary or a permanent shift? Why?

So this could be a temporary shift, given the remarkable persistence of the big guys, and the fact that remote work could fade or be subsumed by “hybrid” work with more techies tethered to offices.

With that said, maybe this is an inflection point. Tech is maturing, and mature industries tend to spread out more. What’s more, Big Tech’s urgent search for talent — especially diverse talent — could well alter the sector’s future geography. Hiring associated with new satellite offices in new places such as the Southeast could alone make a difference.

3/ Is there an innovation/productivity case for trying to promote further or faster decentralization of tech? Why would we want to do this?

There are several reasons to favor greater decentralization of the tech sector. To be clear, no one should be talking about erasing the unique innovation power of the great “superstar” concentrations. Powerful “agglomeration” economies in the big tech hubs are critical assets of U.S. vitality and competitiveness. Yet it is clear the US tech map has grown too narrow. Too much tech in too few places has driven spiraling housing costs there and likely driven groupthink. Likewise, too little tech in most places has depressed the number large dynamic ecosystems, left most communities remote from our greatest source of economic mobility, and likely limited tech’s work on key use cases in the “rest” of the country. So there are clear economic reasons to seek more diffusion of tech in the US. Quite frankly, the US needs more sizable tech hubs.

4/ What sorts of policies would promote further or faster decentralization of tech?

Fortunately we know some of what works, from growth stories like Seattle, the Research Triangle, or even New York. Major research universities, plentiful research money, and abundant STEM and digital workforce training are proven inputs. Meanwhile, quality place-making is increasingly being recognized as an essential attractor of talent and facilitator of connections. States can do some of this, but it will take federal investments to disrupt the current path dependency of hyper-concentration.

5/ Is there a US case of government policy intentionally and successfully building a tech hub? Silicon Valley certainly benefited from government but there was no top-down plan there.

“Top-down” plans don’t work and really aren’t what anyone is calling for. What is needed, by contrast, are major federal investments surged into promising regions to catalyze and support bottom-up, public-private strategic partnerships. In many cases that is the only somewhat intentional effect of federal R&D flows into university complexes as in Madison, St. Louis, or Austin. Among these the growth of the Research Triangle in North Carolina probably has been the most intentional and successful. But I think we’re seeing more intentional efforts.

Micro Reads

🔮 The Future is Vast: Longtermism’s perspective on humanity’s past, present, and future - Max Roser, Our World in Data | Why should you personally care about the future, especially if you aren’t going to be around in 2050 or 2075? Society, as conservative statesman and political theorist Edmund Burke wrote in 1790, “is a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” Great stuff. This from Roser is pretty good, too: “A catastrophe that ends human history would destroy the vast future that humanity would otherwise have. And it would be horrific for those who will be alive at that time. The people who live then will be just as real as you or me. They will exist, they just don’t exist yet. They will feel the sun on their skin and they will enjoy a swim in the sea. They will have the same hopes, they will feel the same pain.”

⚡ American energy innovation’s big moment- Lexington, The Economist | Russia's invasion of Ukraine may provide the US with an unexpected opportunity to take serious action toward a green energy future. And while the Department of Energy is already working on research projects to pull carbon out of the atmosphere and reduce grid storage and hydrogen production costs, deploying such innovations is another task. On the demand side, climate policy can raise the cost of carbon pollution to make green tech more appealing, and a national industrial policy could help to boost supply. So as the world considers the geopolitical necessity of moving beyond oil and gas, America has a chance to lead the energy transition. “The question is whether at least a little of the spirit will arise in Congress. Don’t hold your breath. But don’t count it out, either. The politics of national security, supply chains, energy and climate are in flux, deeply interconnected and capable of inspiring surprising coalitions even there.”

⤴ Flywheels of progress - Jason Crawford, Roots of Progress | Like a flywheel, progress isn't easy to get started (see: all of human history until just a few centuries ago) but once it gets going, it has a lot of momentum. Progress begets more progress in self-reinforcing cycles: New technologies give us the toolkit to create further technological advances; economic growth creates the wealth necessary to fund new research that drives further growth; improvements in agriculture and medicine give rise to larger populations of innovators who pioneer further improvements; and "the more progress we make, the more people believe it is possible and desirable," among other feedback loops at work in the economy.

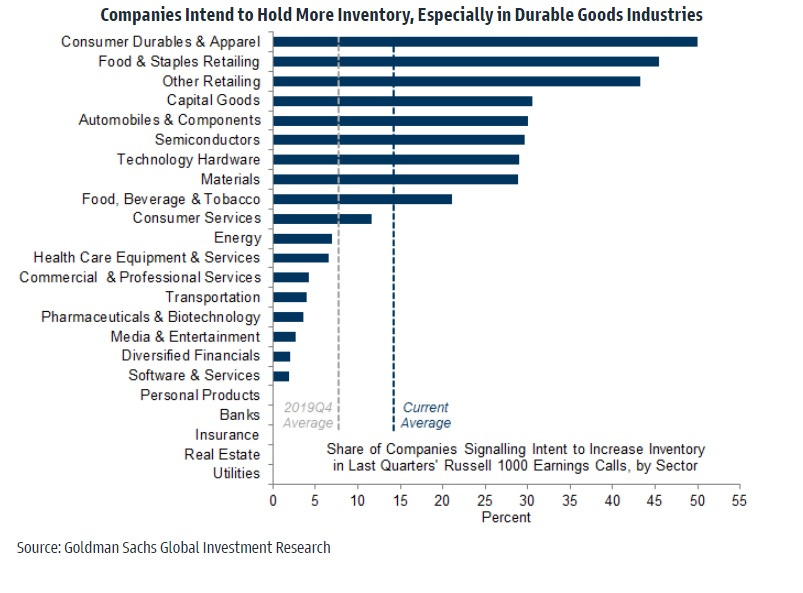

⛓ Strengthening Supply Chain Resilience: Reshoring, Diversification, and Inventory Overstocking - David Mericle, Goldman Sachs | One of the most insightful pieces of Wall Street research that I’ve seen in some time. It addresses how business is attempting to make itself more resilient in a post-pandemic world where the potential for military conflict seems to be growing. For companies, enhanced resilience could take three forms, according to GS: reshoring foreign production to the US, diversifying supply chains, and overstocking inventories. Of the three, inventory overstocking is the approach that’s furthest along. GS:

Earnings call transcripts show that the share of companies that report plans to target a permanently high level of inventory has increased sharply, especially in durable goods sectors. Our manufacturing sector analysts corroborate this and report that companies in their coverage are targeting inventory-to-sales ratios roughly 5% higher than before the pandemic on average.

Nano Reads

▶ Electric Planes Are Coming Sooner Than You Think - Elissa Garay, AFAR |

▶ First ever gene therapy gel corrects rare genetic skin condition - Alice Klein, New Scientist |

▶ Why Universal High-Speed Internet Access Could Be Worth Trillions - Chicago Booth Review |

▶ COVID-19 vaccines: A shot in the arm for the economy - Niels-Jakob Hansen, Rui C. Mano, VoxEU |

▶ The war that put Silicon Valley in its place - Janan Ganesh, FT |

▶ Vetocracy, the costs of vetoes and inaction - Will Rinehart, CGO |

▶ Why We Have To Give Up On Endless Economic Growth - Dominic Boyer, Noema |

▶ Thinking through the unthinkable - Bryan Walsh |