⤴ From Web3 to the space economy, we should avoid knee-jerk skepticism about emerging tech

Also: 5 Quick Questions for … economist Trevon Logan on the economics of American slavery

In This Issue

The Essay: From Web3 to the space economy, we should avoid knee-jerk skepticism about emerging technology sectors

5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for … economist Trevon Logan on the economics of American slavery

Micro Reads: AI powering growth, environmental regulation, global supercomputing, and more

Quote of the Issue

“We believe that a market free enough to communicate useful information through prices, and to utilize that information through decisions made by highly motivated and knowledgeable people (at least at the margin), is likely to operate relatively effectively and smoothly. This concept has been dimmed by a flood of anti-growth, anti-business, anti-middle class, and elitist attitudes.” - Herman Kahn

The Essay

⤴ From Web3 to the space economy, we should avoid knee-jerk skepticism about emerging technology sectors

Nearly 30 years ago, Fast Company magazine called 1995 “The Year That Changed Everything.” And the World Wide Web was a big reason for that claim. Thanks to the emergence of the web, the internet had come to the broad American public. The number of web servers exploded, Netscape went public, and companies rushed to set up websites. As The New York Times put it in December of that year, “By now, the World Wide Web is a full-fledged media star, hailed and hyped, part technology and part fashion accessory.”

Yet it still wasn’t obvious to everyone that the webernet was the Next Big Thing. Almost certainly bigger than interactive television, sure, but maybe not as big as DVDs, scheduled to hit the US consumer market later in 1996. It was in a 1995 issue of Newsweek that technologist and author Clifford Stoll wrote an infamous howler of an essay, “The Internet? Bah!,” in which he dismissed many possible web use cases that turned out to be popular and profitable. “Even if there were a trustworthy way to send money over the Internet — which there isn’t — the network is missing a most essential ingredient of capitalism: salespeople,” Stoll wrote back then.

(By the way, global e-commerce is expected to total some $5.6 trillion this year.)

Now given that my professional career mostly overlaps with the rise (and then explosion) of the internet and web, these technologies have greatly affected how I view emerging tech more broadly. I don’t rush toward knee-jerk skepticism and hand-waving dismissal. Recently, for instance, former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke had little good to say about Bitcoin in a recent CNBC appearance.

My problem with this is not so much with Bernanke’s remarks as with those who took his words as a blanket and comprehensive dismissal of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology in general. What will be the massively important market manifestations of blockchain, crypto, and NFTs, core technologies of Web3? It’s still pretty early. If many tech analysts are right, it’s about as early for Web3 now as it was for Web Classic in 1995.

What’s the big deal about Web3?

The Web3 enthusiasts at venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, or a16z, also agree it’s early, but add that there are plenty of reasons to be optimistic about the future even if no one really understands exactly what that future will look like. How early is it? According to the firm’s inaugural “State of Crypto Report,” published last month, “there are somewhere between seven million and 50 million active Ethereum users today … Analogizing to the early commercial internet, that puts us somewhere circa 1995 in terms of development.”

It took another decade to hit a billion web users “right around the time web2 started taking shape amid the founding of future giants such as Facebook and YouTube.” Even so, a16z points to various fledgling firms doing things that suggest the sector’s potential beyond creator payouts and pure crypto speculation:

Who will be the big Web3 winners in the early 2030s? Maybe some of the above firms. Maybe none of the above firms. It’s still the age of experimentation in products and business models. And it would be wise for Washington to think hard about that reality when considering regulation.

What’s the big deal about a space economy?

Now I’ll be honest, I’m far more interested — at least here in June 2022 — in the emerging space economy than the emerging Web3, but I see a relevant commonality. Conversation about either leads to a demand to know its “killer app.” What are we going to do in space? Float around and look at the stars?

A legit variant of that question came up in a recent chat I had with my fellow AEI scholar (and author/columnist) Jonah Goldberg on his The Remnant podcast. After I mentioned that Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin rocket company has joined with several other companies in plans to build their own space station, Goldberg replied: “I did not know that we’re 10, 15, 20 years out from having big industrial office parks in space. … What is the ROI on that? ‘We’ve got to get these office parks up there to do X.’ Is it to build way stations to go to Mars? Can we make better ball bearings?”

My somewhat rambling (as is my style) answer:

The big answer to that is, they’re not entirely sure. Ideally, they would like to have very large — and this is what Jeff Bezos has talked about — industrial parks up there to make things that we don’t want to make on Earth. Environmentally dirty things. More to the point, at least in the near term, there’s been talk about different kinds of fiber optic cables which would be much more efficient than what you can make on Earth. There are ideas for drugs that would be much easier to make in space because of the lack of gravity. But I don’t think they know. When I talk to people who are building these, they’re like, “Well, you know, a lot of what we do on the internet today was not completely obvious to people in 1995.” And I think that’s the attitude that you have to take. It would be helpful if you wanted to build space-based solar power where you can have huge reflectors in space, you can beam the energy down to Earth. That’s a possibility. I think the true answer is that we don’t know yet what the killer app is, but I’m eager to find out.

If you’re looking for a better answer, more broadly, you can check out my recent essay (from which the below image comes) “America is starting a New Space Age. And it's a problem that many Americans don't know about it.” that explored a recent Citigroup report on the space economy. I would also recommend a March 2022 Rand Corporation report, “Future Uses of Space Out to 2050.” Taken together, they give a pretty substantive overview of what we can reasonably speculate today regarding the economic potential of space.

The shape of space things to come

Let’s focus on what we can do in orbit that’s mostly to the direct benefit of people back on Earth. Let’s set aside the potential benefits of moon and asteroid mining, how Solar System colonization reduces existential risk to humanity, and the gains to the upstream companies enabling a space economy.

Energy. There’s no reason humanity should have an energy-constrained civilization. Rand: “Solar power represents a key space-based energy source given the relative lack of sunlight filtering through Earth’s atmosphere, and potential for continuous line of sight with the sun depending on the orbit used. … [Future] possibilities include establishing large orbital collectors to generate solar power in space and transmit it to terrestrial grids wirelessly through use of microwave transmitters or laser emitters. First proposed in 1968 by engineer Peter Glaser, technological advances could make this concept a reality by 2050.”

Manufacturing. Again, it’s early, but we already know of several products where experiments have shown better outcomes in microgravity environments, such as exotic fiber optic cable, silicon carbide wafers to power electronics and LED lights (90 percent less power losses than Earth-produced wafers), and high-performance alloys with a more uniform internal structure. Then there’s the Bezos dream of space factories allowing the deindustrialization of Earth.

Biotechnology and medicine. A microgravity environment “could potentially help companies conduct better and cheaper research to discover new proteins and drug treatments. Another area that is a focus for biotech companies is 3D-printing artificial organs in a microgravity environment. In the absence of gravitational forces, lower-viscosity bioinks can be used, improving the printability of bioinks and the viability of cells. This allows the creation of more complex tissue structures.”

Back to the internet and the 1990s: One of the all-time great decisions by the US government came during the 1990s with moves that favored a lightly regulated, commercialized internet. As former FCC chairman William Kennard said in 1999, “I want to create an oasis from regulation in the broadband world, so that any company, using any technology, will have incentives to deploy broadband in an unregulated or significantly deregulated environment.” That’s the initial attitude modern regulators and legislators should take when approaching emerging tech.

Finally, the skepticism and lack of imagination that sometimes surrounded the rise of the internet and web — apart from 1990s stock market performance — should make us cautious about dismissing or avoiding ambitious tech speculation, whether it's about new energy sources, radical health treatments, or new ways of getting from here to there (even at hypersonic speeds.) Indeed, too often such speculation overly focuses on potential costs rather than benefits. This plays into what I call the Down Wing Doom Loop: Bad ideas and bad stories lead to bad policy, bad policy leads to bad growth, and bad growth cements bad ideas and encourages more bad stories. Rinse, repeat, and retreat. The point of this newsletter is to help America permanently escape that cycle of stagnation.

5QQ

💡 5 Quick Questions for … economist Trevon Logan on the economics of American slavery

One recent essay on American economic history that caught my eye was “Slavery Was Never an American Economic Engine” by Ohio State University economist Trevon Logan. To find out more about Logan’s work — including the upcoming “The Great American Productivity Gain: Emancipation and Aggregate Productivity Growth” paper he’s writing with the University of Chicago’s Richard Hornbeck that informs this chat — I connected with him to ask a few questions.

1/ You’ve written that we need to revisit "the idea that slavery in the U.S., while morally wrong, was nonetheless an 'economically productive' practice that helped form the foundation of American capitalism." What is the basis of this idea and why does it seem to be a commonly held belief currently?

This erroneous belief is based on thinking about enslavement from the perspective of the enslaver only. That is, if enslaved people are providing their labor, you need to consider the cost of enslavement to them and not to the enslaver. It basically boils down to not considering the value of freedom to the people who are freed.

2/ You write that "emancipation actually delivered the largest positive productivity shock in U.S. history," constituting 10–20 percent of GDP. How did you go about determining that?

Aggregate productivity increased after emancipation because the economic value produced through the institution of slavery came at immensely large costs imposed upon enslaved people that reduced aggregate productivity (or the total value of output minus total costs incurred). Given that there were 4 million enslaved people in the United States on the eve of the Civil War, or 13 percent of the total population, the aggregate productivity gains from emancipation were likely substantial. While output declined substantially in the South after emancipation, total input costs declined so substantially that emancipation represents by far the largest annual increase in aggregate productivity in American history.

3/ Why is it important to set the record straight on the economic inefficiency of America's chattel slavery system? Why does this matter in 2022?

Characterizations of slavery as efficient and productive reflect the perspective of enslavers: the benefits and costs for slave owners and market transactions oriented around extracting value from enslaved people. I’m emphasizing that slavery was deeply inefficient because there was a massive externality: enslavers considered only the private marginal benefits and private marginal costs of slave labor when making production decisions in the antebellum era, but did not internalize the further costs of slavery imposed on enslaved people. Even if enslaved people had received 100% of their marginal product, I would expect that compensation to be less than the costs of slavery incurred by enslaved people. Indeed, that is the “inefficiency'“ of slavery: enslaved people were coerced to work under conditions with immense costs to themselves, which exceeded the value of output they produced. Further, living under enslavement imposed further costs on enslaved people even beyond time spent working and the intensity of that work as enslavement is not analogous to voluntary labor markets. Viewing enslavement as a labor status obscures the fact that it was an assigned identity which alters the way that we should think about productivity. It maters today because we are still, in 2022, not thinking about the enslaved.

4/ Some may assume your piece is meant to rebut The 1619 Project, but you've said otherwise. What are they missing?

The 1619 Project is about the central role that enslavement (and its deeply related process of racialization) played in the founding of the nation down to this day. We know that slavery was quite profitable for enslavers, for Northern financiers, for insurance companies, for land speculators, etc. It’s critical to understand that the political power of the planter class was only temporarily halted during Reconstruction. Slavery is an enduring arc, and for whatever reason we want to treat it as an aberration. My piece is about correctly noting the economic losses we are willing to sustain in order to keep these systems afloat. Profit for some (the master class, the top 1% today) does not imply that the system is economically efficient. Enslavement was a gross misallocation of resources. Even today, economists have noted that discrimination leads to misallocation. That is the point I’m making.

5/ Surveying the economic history of slavery in America and its legacy, what are the biggest questions that remain open?

I think there are several open questions, and most are at the nexus of economic history and narrative history. One question is, what do we learn about the economics of slavery by extending back from 1860? That is, how much of what we think about the institution is formed by looking at the “winners” in 1860? Is there more/less variability in 1850? Another question is the role of slavery in the financial independence of White women. Stephanie E. Jones-Rodgers has convinced me that coverture was one institution that was partially overcome in the antebellum South, and White women were very active in all aspects of enslavement. This raises two questions: [First,] why have we accepted a narrative of passive White women in the institution? [Second], were White women making similar or different decisions about enslavement relative to White men? The last set of questions has to do with the development of large plantations. How did the institution change after the Panic of 1837? How did the Jacksonian policy undermine the small yeoman farmers he claimed to champion?

Micro Reads

▶ Huge “foundation models” are turbo-charging AI progress - The Economist | . “‘AI models used to be very speculative and artisanal, but now they have become predictable to develop,’ explains Jack Clark, a co-founder of Anthropic, an ai startup, and author of a widely read newsletter. ‘AI is moving into its industrial age.’ The analogy suggests potentially huge economic impacts. In the 1990s economic historians started talking about ‘general-purpose technologies’ as key factors driving long-term productivity growth. Key attributes of these GPTs were held to include rapid improvement in the core technology, broad applicability across sectors and spillover—the stimulation of new innovations in associated products, services and business practices. Think printing presses, steam engines and electric motors. The new models’ achievements have made AI look a lot more like a GPT than it used to. Mr Etzioni estimates that more than 80% of AI research is now focused on foundation models—which is the same as the share of his time that Kevin Scott, Microsoft’s chief technology officer, says he devotes to them.”

▶ E.P.A., Reversing Trump, Will Restore States’ Power to Block Pipelines - Lisa Friedman, NYT | “The Biden administration’s proposed changes essentially would restore the conditions that existed before the Trump presidency. They come as Mr. Biden is calling on the oil and gas industry to step up production to relieve high prices at the pump. Energy trade groups said they were concerned the new regulation could block infrastructure they believe is needed to meet demand. .. Republicans criticized the Biden administration’s plans as adding needless red tape while allowing fossil fuel opponents to create barriers for oil and gas projects.”

▶ NASA audit reveals massive overruns in SLS mobile launch platform - Jeff Foust, Space News |

▶ Flying taxis, delivery drones and more are finally taking off - Joann Muller, Axios |

▶ Why wasn't the Steam Engine Invented Earlier? Part I - Anton Howes, Age of Invention |

▶ Lasers could cut lifespan of nuclear waste from “a million years to 30 minutes,” says Nobel laureate - Robby Berman, Free Think |

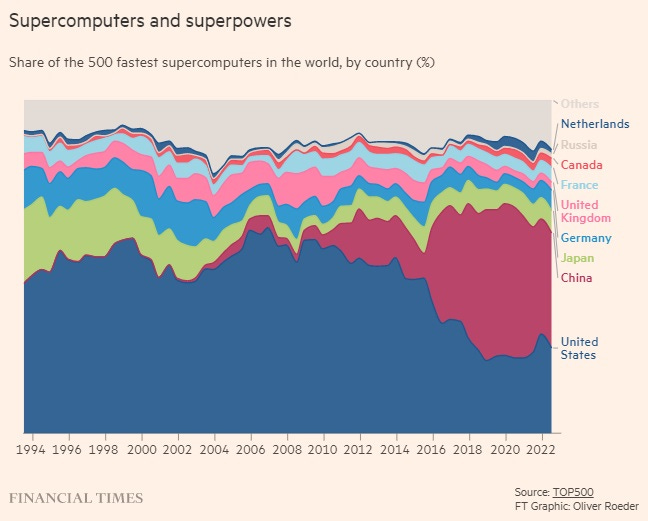

▶ The global race for supercomputing power - Oliver Roeder, FT | “The most powerful supercomputer ever to exist sits on the leafy campus of Oak Ridge National Laboratory, a US Department of Energy facility in Tennessee. The $600mn machine, called Frontier, consists of 74 cabinets, each as heavy as a truck, cooled by 6,000 gallons of water a minute and strung together with 90 miles of networking cable. It is also the first recorded supercomputer capable of an exaflop per second — a billion billion operations. We’ve reached exascale, long a holy grail of computing. “