🚀 Faster, Please!: Week in Review+ #2

Talking to NASA's chief economist, “The Limits to Growth” at 50, Russia's anti-futurism, and much, much more ...

My free and paid subscribers: welcome to Faster, Please!: Week in Review+. As usual, I covered a wide range of subjects in the essays, Q&As, and micro reads on Monday and Thursday.

But this weekend issue isn’t just a punchy recap for everyone. (Although it is that, too. See below.) There’s also beautiful fresh content. I recently did a fun podcast chat with Alex MacDonald, NASA’s chief economist and author of The Long Space Age: The Economic Origins of Space Exploration from Colonial America to the Cold War. After our recorded conversation, I asked Alex Five Quick Questions just for my Faster, Please! subscribers. Good stuff. Enjoy!

Melior Mundus

In This Issue

Weekend 5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for … Alex MacDonald, NASA’s chief economist and author of The Long Space Age: The Economic Origins of Space Exploration from Colonial America to the Cold War

Essay Highlights: The Limits to Growth at 50: Still saving the Earth at the expense of humanity; A country without a positive vision of the future has no future. Just look at Russia.

Best of 5QQ: MIT scientist Andrew McAfee, author of More From Less: How We Finally Learned to Prosper Using Fewer Resources — and What Happens Next; Northwestern University economic historian Joel Mokyr, author of The Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy

Best of Micro Reads

5QQ — Weekend Edition

Alex MacDonald is NASA’s chief economist and author of The Long Space Age: The Economic Origins of Space Exploration from Colonial America to the Cold War. I had a few questions for him the other day, five to be exact.

1/ My first question is about the twin revolutions in space economics. First, we now have the public sector and the private sector. Second, we have a change in the economics of space, a huge decline in launch costs. Tell me why these two twin revolutions are significant.

The change in launch costs allows for more missions for the same price when paid for by government customers, but also commercial customers. This is allowing us to do more missions to the Moon than we ever have done before robotically. This is allowing for us to do new types of low-cost Earth science missions and low-cost missions to the outer planets.

The trend of who is paying for space is, I think, important because it allows for entirely new types of activities to happen in space. The Inspiration4 mission is a great example of that. The Inspiration4 mission happened on a vehicle, the commercial crew Dragon vehicle, that had been developed for a NASA program, but it wasn't a NASA mission. It was a private mission that allowed for that set of space travelers to tell their story in a fundamentally new way. I think we're just at the beginning of that type of transition. When private individuals can pay for their own missions, entirely new types of missions are possible.

2/ This is a question that comes up a lot when I do panels. People will ask, "What is the killer app of us being in space?" Particularly with the space economy, they'll say, "Well, is it tourism? Is it orbital factories? Is it something just we don't know?" I was curious what your thoughts are.

It is a perennial question. I'll give you two answers. If you look at the current commercial space economy, by far the majority of commercial space activity is communication satellites. The current investment in tens of thousands of unit satellite constellations for space internet tells you that is not looking like it's going to decrease as a share of the total commercial space economy. Right now, the killer app for space, as successfully predicted by Arthur C. Clarke in the first half of the 20th century, is communication satellites.

However, I would also say that the other killer app for space is humans. We continue to launch humans into space because of all of the different things that both humans are able to do in space, but also that humans in space inspires [us]. … There's often been a question as to why we launch humans into space, amongst people who don't find that particular field of astronautics as exciting. Yet I would argue that we go into space in large part because there are enough of us on this planet who are sufficiently inspired by the concept of human spaceflight that we continue to organize our resources to make it happen. That idea of humans traveling out into space, of potentially living in space permanently one day, I would say that that story itself is one of the killer apps.

3/ One of my favorite shows is For All Mankind. The scenario there is the Soviets win the space race, and because of this, we just keep racing with the Soviets. We don't downgrade; we just keep pushing forward. Do you ever think about where we would be if we had made some different choices in the 1970s?

Well, I don't engage in counterfactual thinking too often. I have enough challenges deciphering what's happening in the world today. I love For All Mankind as well. I think they've done a great job of laying out that counterfactual. I also think that show points to a really important aspect of space flight and space exploration that we need to very seriously think about and consider: the likelihood that we won't be the only nation out in space, and that given the human history of conflict, that it's very possible that that conflict could extend to space. I think For All Mankind shows why that would be such a tragic, and potentially cataclysmic, outcome. I think it is helpful to go through these counterfactuals to show us some of the risks that might lie ahead. I think anyone who makes it all the way through season two of For All Mankind can do exactly that.

4/ People today view the involvement of rich guys in the space program as something very novel, but your research shows it's not novel at all. What's the history there?

In the 19th century, the majority of large astronomical observatories in the United States were funded by wealthy individuals or by groups of wealthy individuals. Some of the individuals were Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, as well as folks who are slightly more obscure but actually spent more money, like James Lick. That continued into the 20th century with the Guggenheim family becoming the patrons of the first entrepreneur of spaceflight rocketry, Robert Goddard, in the 1920s. So wealthy individuals funding space exploration activities is actually, arguably, the origins of space exploration in this country rather than an anomaly.

5/ Someone in your job in the 2060s, 100th anniversary of Apollo, if they're going to tell the story of American space history and economic history, what might that story look like over the next 40 years or so? What will it be a story of?

Back when I was in charge of a program called the Emerging Space Office, I did, with my colleagues, lay the story out to 2044. So folks can look at the Emerging Space report and see how far that takes us to that point. We talked about there being a multiplicity of commercial space stations in low-Earth orbit, about there being a wide variety of activities on the lunar surface, publicly funded activities, international activities, and some privately funded activities as well, as we start to develop a more permanent presence on the lunar surface.

When we wrote the report in 2014 or so, we had talked about 2044 as just being around the time of a first landing on Mars, and of course, also about us starting to assay and begin to work with asteroids in ways that might prepare us for either planetary defense, or potentially one day using those asteroid resources for economic purposes. I think those are the big trends, as well as there being a significant enmeshment of the Earth in an increasing number of communication satellites, as well as Earth observation satellites that do everything from intelligence to greenhouse gas monitoring and verification.

I think that roughly is the state in 2069 as well, except more of all of the above. But I would also say that by then we will probably have significantly identified "nearby" exoplanets with potentially significant biosignatures. By nearby, I mean out to 100 light-years. Although I don't think we will be anywhere near warp drives, I think that those discoveries which will happen over the next 40 years or so will inspire new stories about how we may ultimately be able to explore nearby star systems as well.

Essay Highlights

🌎 The Limits to Growth at 50: Still saving the Earth at the expense of humanity

“It is hardly surprising that dead rabbits are pulled out of the hat when nothing but dead bunnies have been put in” is how Nobel laureate economist William Nordhaus once described the inherently gloomy scientific modeling of The Limits to Growth. That alarming and alarmingly influential 1972 environmental report debuted 50 years ago last week. It told a story of shocking future scarcity, of a world running out of everything and then running down. Oh, and then collapsing at some point in the 21st century. Too much consumption by too many people.

Yet today the world is richer and less hungry. And commodity prices suggest we aren’t running out of everything. (Between 1980 and 2017, the real price of a broad basket of commodities decreased by 36.3 percent.) Many economists were unimpressed by LtG back then and still today. They tend to think that technological progress and market mechanisms can prevent scarcity of natural resources from becoming a hard limit to growth. The Shale Revolution does not compute, nor do potential breakthroughs in advanced nuclear, nuclear fusion, and advanced geothermal (much less, you know, asteroid mining). It’s up to us and our actions, not math or models, to determine our destiny as a species.

😞 A country without a positive vision of the future has no future. Just look at Russia.

As Dutch futurist Frederick Polak famously put it, any culture “turning aside from its own heritage of positive visions of the future, or actively at work in changing these positive visions into negative ones, has no future.” Russia seems to qualify, at least according to the 2019 study “The Image of the Future of Contemporary Russia” published in the Journal of Future Studies by researchers Inga Zheltikova and Elena Khokhlova of Russia’s Orel State University. Zheltikova and Khokhlova examined film, fashion, government projects, literature, scientific forecasts, and surveys “as sources of transmission” of contemporary Russian images of the future. And what they found was a Volga of pessimism about the future winding its way through Russian society. (“Literary images of the future of Russia as a whole are rather pessimistic.”)

Russia also scores abysmally as a future-oriented culture — a trait correlated with higher GDP, innovativeness, and happiness — when asked to assign importance to such questions as “More people should live for the present than for the future.” In a 2019 Moscow Times column, Vladislav Inozemtsev, director of the Center for Post-Industrial Studies in Moscow, put it this way:

I believe that change is unlikely. Mostly because the Russian ruling elites have no ideology that could join them and force them to act in a forward-looking way. Today, ordinary people survive on their own and bureaucrats also act on their own, enriching themselves as much as they can. Neither the lower social strata nor the elites have any vision of the future. The absence of such a vision generates a deficit of historical optimism, pushing the system towards a debacle.

America isn’t Russia, of course. But perhaps there is an applicable lesson for America about the importance and interaction of an economy that generates opportunity and mobilityv and a culture that supports a creative imagining of a future worth living in.

Best of Five Quick Questions

🌼 Andrew McAfee is co-director of the Initiative on the Digital Economy and a principal research scientist at the MIT Sloan School of Management. His most recent book More From Less: How We Finally Learned to Prosper Using Fewer Resources — and What Happens Next was published in 2019. From the March 7, 2022 issue of Faster, Please!:

Pethokoukis: Do you ever wonder what the world would be like if we had built upon the optimism of the immediate postwar decades — while still dealing with pollution — and not (to me at least) having overcorrected by devaluing the benefits of growth?

McAfee: The thought makes me weep. If we had taken seriously Eisenhower's idea of "atoms for peace" starting in the 50s, how much poverty, malnutrition, and misery would we have avoided? How many fewer deaths from fossil fuel pollution? How much less global warming? It's easily our biggest missed opportunity as a species.

📈 In his fantastic 2018 book A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy, Joel Mokyr, an economic historian at Northwestern University, contends that a culture of growth in early modern Europe and the European Enlightenment laid the foundations for the Industrial Revolution and the Great Enrichment. From the March 10, 2022 issue:

Pethokoukis: You’ve written about the “culture of growth” that led to the Industrial Revolution. Do America and the West currently display the beliefs, values, and preferences necessary to sustain or accelerate technological progress — given the inevitable disruption it will cause?

McAfee: Yes, they do. There was always disruption due to technological progress, and there always will be. A healthy and rational society provides cushions and safety nets to losers and then moves ahead. Damn the torpedoes, full steam ahead. The concern is that some obsessed single-issue lobby can block certain necessary avenues of progress like nuclear power and stem-cell research.

Best of Micro Reads

🌐 The Economic Impact of Cyberattacks - Goldman Sachs | It’s never good when military analysis starts creeping into Wall research. And not surprisingly, I’m seeing a lot of that sort of thing right now given the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Malicious cyberattacks do about $1tn in damage globally per year. While no individual cyberattack has had a major macroeconomic impact in the US, cyberattacks have imposed large costs on other countries. The most destructive individual cyberattack to date, the 2017 NotPetya attack directed at Ukraine, is estimated to have inflicted over $10bn in damages—just over 10% of Ukraine’s GDP at the time. .. Past cyberattacks carried out by state actors have mostly been used for information gathering, not for destruction of equipment or data. This makes it difficult to estimate the potential impact of a cyberwar between governments. A few studies have attempted to model the potential economic costs of improbable but technologically possible cyberattacks on US critical infrastructure. A study from the NY Fed estimates that a successful attack on one of the largest US banks could interrupt 5%-35% of daily payments, and a study from Lloyds estimates that an extreme attack on the Northeast US’s power grid could cause $250bn-$1tn in economic damages.

This chart is both worrisome and encouraging:

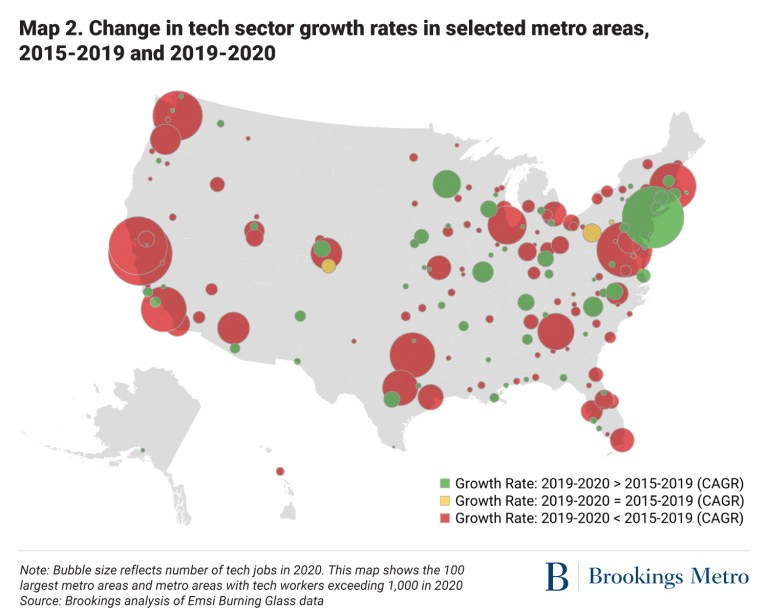

💡 Superstars, rising stars, and the rest: Pandemic trends and shifts in the geography of tech - Mark Muro and Yang Yui, Brookings | The success of "superstar" cities like San Francisco has had America's heartland itching to create the next Silicon Valley for decades, yet technology companies have remained geographically concentrated. But with the rise of remote work during the pandemic, is tech beginning to spread across the country? While the tech sector was further concentrating before the COVID-19 outbreak, the last two years have seen some decentralization. The data show that "employment growth slowed in some of the biggest tech 'superstars' and increased in other midsized and smaller markets, including smaller quality-of-life meccas and college towns."

![The Long Space Age: The Economic Origins of Space Exploration from Colonial America to the Cold War by [Alexander MacDonald] The Long Space Age: The Economic Origins of Space Exploration from Colonial America to the Cold War by [Alexander MacDonald]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Ikgi!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd1e68e84-233d-470e-8e56-fdf8d2be774c_331x500.jpeg)