💣 Doomsday economics: What if someone explodes a nuclear bomb?

Also: 5 Quick Questions for . . . journalist Derek Thompson on the 'abundance agenda.'

“. . . almost all of humanity’s life lies in the future, almost everything of value lies in the future as well: almost all the flourishing; almost all the beauty; our greatest achievements; our most just societies; our most profound discoveries. We can continue our progress on prosperity, health, justice, freedom and moral thought. We can create a world of wellbeing and flourishing that challenges our capacity to imagine. And if we protect that world from catastrophe, it could last millions of centuries.” - Toby Ord, The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity

In This Issue

Long Read: Doomsday economics: What if someone explodes a nuclear bomb?

5QQ: 5 Quick Questions for . . . journalist Derek Thompson on the “abundance agenda.”

Micro Reads: FDA failures, xenotransplantation, artificial wombs, and more . . .

Nano Reads

Long Read

💣 Doomsday economics: What if someone explodes a nuclear bomb?

When I typically write about a “coming boom,” I’m referring to the prospects for a rapid acceleration in economic growth and technological progress. But the unsettling way that 2022 has started means a different kind of “boom” has been top of mind:

In The Washington Post on Monday, Jon Wolfsthal, arms control and nonproliferation specialist on President Obama’s National Security Council, warns the “risk of a nuclear conflict erupting between the United States and Russia, and increasingly between the United States and China, is dangerously high.”

Over at the Defense One, another Obama administration security official, Evelyn Farkas, earlier this month raised the “horrible possibility” that an invasion of Ukraine would mean “Americans, with our European allies, must use our military to roll back Russians — even at risk of direct combat.”

Then in the background there’s the accelerating hypersonic arms race between China, Russia, and the US. (A Financial Times “Year in word” selection for 2021 was “hypersonic: (adjective) describing a type of weapon or aircraft that flies at more than Mach 5 — or five times the speed of sound.”

And on Thursday, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists kept its “Doomsday Clock at a mere 100 seconds to midnight, “the most dangerous situation that humanity has ever faced.” That analysis, while taking into account nuclear issues, also factors other risks such as climate change and “disruptive” technologies such as AI, cyber attacks, and genetic editing.

So, yes, I’ve been thinking a bit lately about nuclear war. And for the purpose of this newsletter, I’ve especially been pondering the economic impact of such an escalation. Now because I’m weird, the first thing that pops into my head is that much-discussed question of whether Americans are better off today than, say, the 1970s or 1980s. It’s an issue I’ve spent considerable time exploring over the years. (Much of the debate revolves around how one selects and defines variables such as wages, compensation, income, mobility, and inflation. Especially inflation.)

And while I think the economic evidence overwhelming suggests a “yes” answer, the dispositive bit of proof has nothing to do with economics: The odds of a catastrophic nuclear war are almost certainly a lot lower today than back during the Cold War. Nuclear arsenals are smaller and less potent. According to the Federation of American Scientists, the number of warheads declined from a peak of 70,000 in 1986 to about 9,500 currently in the military stockpiles for operational use by missiles, aircraft, ships, and submarines. And with the ratcheting down of Cold War tension — and improvement in command-and-control systems — we’ve stopped hearing about all the scary near-misses.

But let’s assume the Doomsday Clock is closer to the truth than my cheery assessment, especially given recent events. Back to economics: What would be the economic impact of a nuclear conflict? Well, so bad that even the mere contemplation of the possibility produces negative economic results. In the 1989 paper “Interest Rates in the Reagan Years,” Patric H. Hendershott (Ohio State University) and Joe Peek (Boston College) note evidence that heightened tensions between the US and USSR during President Reagan’s first term “contributed marginally (about a half percentage point) to the high real rates by increasing the feat of nuclear war and thus reducing the private propensity to save.” If the world of the “day after” is one of radiation and nuclear winter, then saving for retirement is less of a priority.

Cold War fears also seem to have suppressed a propensity to highly value stocks. In a 2019 Bloomberg column, Stephen Gandel highlights the work of Nobel laureate economist Robert Shiller in noting that from 1871 through 1990, the average P/E of the stock market was 13.6 and rarely rose above 18. Then something changed. Starting in 1991, the market’s P/E multiple took off. Since then, Gandel continues, it has rarely been below 18, averaging 23 in the 1990s and 19.5 in the 2000s. It’s currently at 25.

So what might have changed to prompt that financial rethink? Gandel (bold by me)

Many factors probably contributed to the market’s valuation shift, but one of the most frequently cited is the so-called peace dividend. The Berlin Wall fell, the Soviet Union collapsed in late 1991, and stocks took off. It’s hard to quantify just how much of a boost came from the downfall of a military superpower and the reduced threat of nuclear war. Interest rates also generally fell to new lows during the period; technology and productivity took off; and 401(k)s blossomed along with many Americans’ attachment to the stock market. But a big lift undoubtedly came from a reshuffling of the world order with the United States firmly on top.

Sidenote: I recall reading a book as a Soviet Politics major in college where the opening vignette imagined traders buying and selling on the floor of a commodities exchange. Suddenly breaking news: The Soviet Union has launched a massive nuclear attack. Markets start to collapse. What should the traders do? Go long, of course. If it’s a false alarm, markets will quickly rally. And if it’s not a false alarm? Then no one is going to care about their portfolios. Instead of buy, buy, buy, it will be bye, bye, bye.

But let’s set aside the notion of a full-scale, “the missiles are flying, hallelujah, hallelujah” global nuclear war. (Fun fact: The world’s nuclear stockpiles aren’t nearly big or powerful enough to lethally irradiate every last bit of the planet. So that’s something, I guess.) Let’s even dismiss the possibility of a far more limited conflict, such as a 100-warhead exchange between India and Pakistan. (About nuclear winter: Computer modeling apparently differs on whether a war of nature could radically alter the climate. It really depends on how much soot gets thrown up into the atmosphere, and there’s a wide range of estimates.)

What would be the impact of even a single nuclear explosion, the first since World War Two? Yes, maybe real interest rates would start rising. (So, too, defense spending.) And stocks falling. But also more than that. From the 2012 paper “The Economic and Policy Consequences of Catastrophes” by Robert S. Pindyck (MIT Sloan School of Management) and Neng Wang (Columbia Business School):

Various studies have assessed the likelihood and impact of the detonation of one or several nuclear weapons (with the yield of the Hiroshima bomb) in major cities. At the high end, Allison (2004) put the probability of this occurring in the next ten years at about 50%! Others put the probability for the next ten years at 1 to 5%. . . . What would be the impact? Possibly a million or more deaths. But the main shock to the capital stock and GDP would be a reduction in trade and economic activity worldwide, as vast resources would have to be devoted to averting further events.

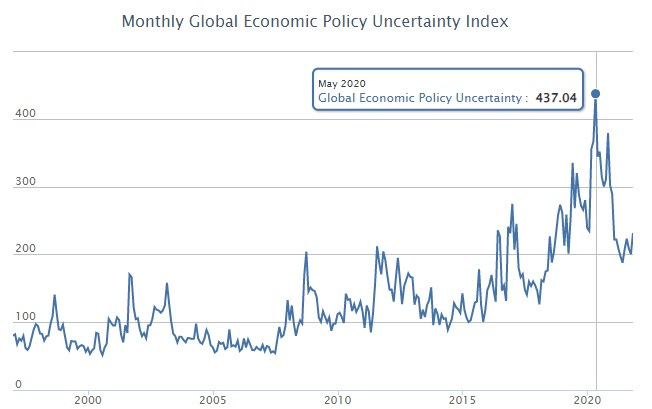

One wonders if an updated version of that study would incorporate what we’ve learned about global supply chains during the pandemic. In addition, there would be massive policy uncertainty, which has been shown to be a real economic drag. Looking at spikes in such uncertainty — including tight presidential elections, the Gulf Wars, the Iraq War, the 9-11 attacks, the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the 2011 debt-ceiling dispute — as measured in part by analyzing newspaper articles, economists Scott R. Baker (Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University), Nicholas Bloom (Stanford University), and Steven J. Davis (Booth School of Business UChicago) wrote in 2015:

Using firm-level data, we find that policy uncertainty raises stock price volatility and reduces investment and employment in policy-sensitive sectors like defense, healthcare, and infrastructure construction. At the macro level, policy uncertainty innovations foreshadow declines in investment, output, and employment in the United States and, in a panel VAR setting, for 12 major economies.

By the way, the uncertainty spike in 2020 was wild:

Now for you ultra-longtermists out there, here’s a positive ending note — and this is supposed to be an optimistic Substack, after all — from The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity by Toby Ord (which also provides the quote leading off this issue of Faster, Please!):

“ … nuclear winter appears unlikely to lead to our extinction. No current researchers on nuclear winter are on record saying that it would and many have explicitly said that it is unlikely. Existential catastrophe via a global unrecoverable collapse of civilization also seems unlikely, especially if we consider somewhere like New Zealand (or the southeast of Australia) which is unlikely to be directly targeted and will avoid the worst effects of nuclear winter by being coastal. It is hard to see why they wouldn’t make it through with most of their technology (and institutions) intact. … My mentor, Derek Parfit, asked us to imagine a devastating nuclear war killing 99 percent of the world’s people. A war that would leave behind a dark age lasting centuries, before the survivors could eventually rebuild civilization to its former heights; humbled, scarred— but undefeated.

5QQ

❓❓❓❓❓ 5 Quick Questions for . . . journalist Derek Thompson on the “abundance agenda.”

Derek Thompson is a staff writer at The Atlantic and the author of the excellent Work in Progress newsletter. He is also the author of the book Hit Makers and the host of the podcast Plain English. A recent Atlantic piece, “A Simple Plan to Solve All of America’s Problems,” examines why scarcity — from rapid tests to masks to supply chain interruptions —seems to be the new norm in the United States. (I also recommend his new piece, “Silicon Valley’s New Obsession: A group of tech founders, crypto billionaires, and star scientists is launching a fleet of science labs.”)

1/ What is the Abundance Agenda thesis?

Throughout the pandemic, the U.S. has dealt with crises of scarcity. We were told to not wear masks in early 2020, because there weren’t enough. We were told not to get booster shots, because there weren’t enough. We were told not to waste rapid tests, because there weren’t enough. Scarcity is the story of the decade. We don’t have enough housing, immigration, semiconductor chips, or clean energy deployment. Scarcity is a policy choice. We should make the opposite choice. The abundance agenda is about identifying what we want more of and making more of it. Sometimes that means spending more money. But sometimes, to get more, you only have to subtract. We can subtract stupid regulations and subtract constrictive immigration policy. That alone would give us an abundance of energy and brilliant people without affecting spending.

2/ Why have we been operating under a Scarcity Agenda for so long?

I don’t know for sure. I’ll give you a few theories. One theory from the left is that the fault is corporate consolidation and plutocracy. Rich companies and individuals want to preserve their wealth and so they’re against increasing the supply of anything that dilutes it. Theory two, from the center-libertarian movement, is that rich modern societies choose to become meta-NIMBYs. We build vetocracies that empower special interests and make it impossible to build as easily as we used to.

3/ How do the current politics of the Democratic and Republican parties fit with an Abundance Agenda?

What I say in the piece is that I want to borrow the best of the left, center, and right with this agenda. I want to build on Ezra Klein’s brilliant formulation of a supply-side progressivism and, in his words, “take innovation as seriously as it takes affordability.” I want to tip my hat to libertarians, who are right to recognize that we can have more with less — more energy, for example, with fewer restrictions on building green tech projects. But I also hold out what might be a silly hope that I can get some conservative Republicans on board. Trumpists talk about national greatness, but what makes a nation truly great is clean and safe spaces, excellent government services, fantastic living conditions, and broadly shared wealth. Let’s make those things abundant.

4/ Does this agenda require a new political party?

I’m optimistic by nature, but I’m pessimistic about the prospects of a successful third political party for all sorts of reasons relating to the rules and construction of the U.S. electoral system. I’ve never voted Republican, so I’m predisposed to say that this is a platform for the Democratic Party. But successful movements really do transcend partisan divides. Gay marriage used to be controversial; then it was arguably coded as a liberal cause; and now I know several gay Republicans. That is nothing if not a moral triumph. The issue of gay marriage moved from outer realm of controversy into the inner realm of obviousness. The abundance agenda can triumph, too, if its goals moves from the outer solar system of American politics into the inner-realm of obviousness.

5/ What are the most important Abundance Agenda policies?

Pass pandemic preparedness legislation that would accelerate vaccine production for the next variant or the next virus. In health care, pass laws to increase the number of U.S. physicians. In housing, more states and cities should follow the example of California in banning single-family zoning. In clean energy, as I wrote, we need a total rethink: way more high-skill immigration to let in the founders of the next great green tech firms; more R&D; more purposeful deployment of solar technology; more regulatory reform to allow for the construction of more solar and wind farms; and a rational approach to nuclear energy that encourages the construction of more plants.

Micro Reads

💉 What America Lost by Delaying the Vaccine Rollout - Brendan Borrell, The Atlantic | As Election Day neared in the fall of 2020, Pfizer expected to deliver Phase 3 clinical trial results by the end of October as part of Operation Warp Speed efforts to fast-track a COVID-19 vaccine. "Then the FDA applied the brakes, telling Pfizer and Moderna that it wanted additional safety data. More specifically, it wanted the companies to have tracked the health of at least half of their clinical-trial subjects for 60 days following the second dose." The FDA's decision delayed vaccine rollout at the most by about two or three weeks, costing 6,000 to 10,000 lives, estimates Claus Kadelka, an Iowa State University mathematician who modeled the counterfactual. The delay may also have been critical for building public confidence in the vaccine's safety. Still, the question remains why the FDA didn't use its compassionate use protocol to innoculate nursing home residents while the vaccines were still pending emergency use authorization.

🧬 Kidneys From a Genetically Altered Pig Are Implanted in a Brain-Dead Patient - Roni Caryn Rabin, The New York Times | A dozen people in the United States die daily waiting for a kidney transplant. Xenotransplantation — transplanting an animal organ into a human patient — could be the solution to the kidney shortage. This announcement comes on the heels of a successful transplant of a heart taken from a pig whose genome had undergone numerous genetic alterations. While xenotransplantation remains experimental, the early results are cause for optimism about a future where patients no longer die waiting for a donor organ. “Kidney failure is refractory, severe and impactful, and we think it needs a radical solution,” said the lead surgeon who “hopes to be able to offer pig kidney transplants to her patients within five years.”

💲 Fed releases long-awaited study on a digital dollar but doesn’t take a position yet on creating one - Jeff Cox, CNBC | The Federal Reserve on Thursday released its long-awaited study of a digital dollar, exploring the pros and cons of the much-debated issue and soliciting public comment. Billed as “the first step in a public discussion between the Federal Reserve and stakeholders about central bank digital currencies,” the 40-page paper shies away from any conclusions about a central bank digital currency, or CBDC. In a report titled “Don't hold your breath waiting for Fedcoin,” JPMorgan “noted that the Fed would only issue a CBDC with ‘clear support from the executive branch and from Congress, ideally in the form of a specific authorizing law.’ In the current political environment, that seems like a long shot.”

⚡ The EV revolution needs an energy surge - John Thornhill, FT | With government subsidies hastening the pace of adoption for electric vehicles, charging demand is set to skyrocket. So a serious buildup of charging infrastructure is needed: more than 200 million electric vehicle charging stations globally by 2030 in order to meet emissions goals. The need for charging investment on a mass scale raises the question of whether markets alone can deliver the necessary infrastructure or if governments have a clear role in regulating and guiding the coming proliferation of EV charging stations.

👶 Womb for improvement - Aria Babu, Works in progress | Artificial wombs could make it possible for “women who cannot give birth [to] still have children if they want to” and ‘save prematurely-born infants as well.” This piece runs through the current challenges, from technology to taboos. Also quite the kicker: “The Book of Genesis was right — the price we pay for the knowledge of good and evil is sorrow when we bring forth children. It is a testament to our capacity for love that most mothers choose to have children despite this, but not all get that choice.”

🧠 Curing Alzheimer’s by Investing in Aging Research - Eli Dourado and Joanne Peng | Researchers are looking for cures and treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, but a broader approach that tackles a deeper understanding of aging itself could deliver medical insights to tackle a host of chronic diseases, according to the authors. If Congress would allow the National Institute on Aging to use funds earmarked for Alzheimer’s research to investigate the broader biology of aging, the NIA could focus on the most promising research opportunities to target aging, improving lives for the elderly and aiding the effort to cure or treat Alzheimer’s. "Promising areas that the NIA could invest in include building tools for understanding molecular mechanisms of aging, establishing and validating aging biomarkers, and funding more early-stage clinical trials for promising drugs."

Nano Reads

☀ The sci-fi genre offering radical hope for living better - David Robson, BBC |

👍 The YIMBYs are starting to win a few - Noah Smith, Noahpinion |

🌐 The Brain Drain That Is Killing America's Economy - Parag Khanna, Time |

📉 Are discoveries and inventions in decline? My long-read Q&A with Didier Sornette - James Pethokoukis, AEI |

🕹 The lies that powered the invention of Pong - Tekla S. Perry, IEEE Spectrum |

🔋 The US Inches Toward Building EV Batteries at Home - Gregory Barber, Wired |

🧬 A $3bn bet on finding the fountain of youth - The Economist |

🤖 Why ‘home robots’ are a lot further away than you think - Tristan Greene, The Next Web |