⚡ AI? CRISPR? Fusion? Can we figure out if the Next Big Thing is already here?

The US economy could use a new 'general purpose technology.' A few of them, actually.

In This Issue

The Essay: Can we figure out if the Next Big Thing is already here?

5QQ: Five Quick Questions for … economist Jason Barr on making a bigger Big Apple

Micro Reads: clean energy deregulation, productivity and pay, gifted school programs

Nano Reads

Quote of the Issue

“But unless the future is marred by a major nuclear war or other disaster, almost all of humanity will be materially better off. … If all goes well, the centuries to come could well be when humanity's true history begins.” - Herman Kahn

💥 Important Update for My Wonderful Faster, Please! Readers and Subscribers

I currently intend to start offering a paid subscription option to Faster, Please! as of February 28. While I’m still working out the exact details, accessing my twice-weekly essays and Q&A interviews with top thinkers (along with some surprises) would be included in that paid subscription, but not the freebie version. I have been writing this newsletter over the past year at night and on weekends. I hope you find it valuable.

My friends: I believe we’re at the start of an amazing period of American (and world) history — the beginning of a Great Acceleration in human progress. It’s the purpose of Faster, Please! both to document these steps/leaps forward and recommend the best ideas to make sure they happen, ASAP. You know, faster, please! I look forward to taking that journey — via economics, tech, public policy, business, history, culture, and a smidgen of politics — over the next months and years with all of you. Let’s make a better world for everyone, together. Melior mundus

The Essay

⚡ Can we figure out if the Next Big Thing is already here?

There have been plenty of emerging technologies in the 2000s hyped as possibly the Next Big Thing. Among them: 3D printing, big data, blockchain, cloud, CRISPR, the internet-of-things, machine learning, quantum computing, and virtual reality. One group of folks doing the hyping is Gartner, the technology research consultancy. All of the previously mentioned technologies have been listed by Gartner in its annual “hype cycle” lists of emergent tech.

To that cluster of innovations, you can add some big advances over the past two years or so. There are, of course, those lifesaving mRNA vaccines. But also cheap, reusable SpaceX rockets, an AI program that can accurately predict protein structures to create new drugs and medical treatments, huge developments in nuclear fusion, and CRISPR genetic editing deployed in the human body for the first time. As I wrote a few issues ago, there’s reason for hope that we are entering a part of the technology cycle marked by drastic rather than incremental innovation.

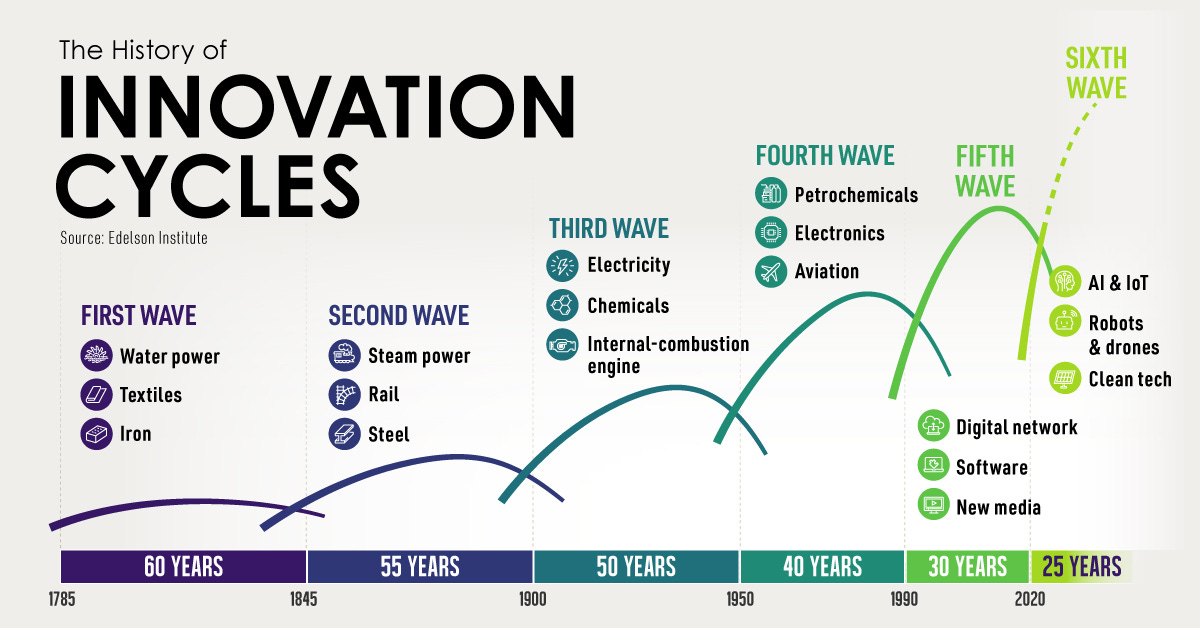

But what qualifies a technology as a Next Big Thing, or NBT? For the purposes of this newsletter, a true NBT is a GPT, or general purpose technology. These are the game-changers, what Northwestern University economist Robert Gordon calls the Great Inventions. Commonly identified GPTs include the steam engine, electrification, the combustion engine, computers, and the internet.

In their 1995 paper “General Purpose Technologies ‘Engines of Growth?,’" economists Timothy F. Bresnahan (Stanford University) and Manuel Trajtenberg (Tel Aviv University) describe GPTs as being characterized by “pervasiveness,” meaning that they’re used as productivity-enhancing inputs in downstream sectors where further innovation in the GPT occurs. “Thus, as GPTs improve, they spread throughout the economy, bringing about generalized productivity gains,” Bresnahan and Trajtenberg write. That last bit of the “innovation loop” is important because discovery and innovation must lead to commercialization that boosts productivity.

Consider the powerful GPT of electrification. The early use case was street lighting and streetcars, but eventually came the downstream application and development of washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and refrigerators. Electrification also led to the reorganization of factories. Well, eventually led to their reorganization. As Stanford economist Paul David explained in his classic 1990 paper “The Dynamo and the Computer,” it took decades for factories to move beyond merely replacing the waterwheels or steam engines driving large groups of machines through systems of pulleys and belts with new electric motors doing much the same thing. Big productivity gains occurred in the 1920s when new factories were built with individual electric motors in each machine.

But here’s the thing: As electrification was happening, it didn’t really look like a GPT, although wildy obvious in retrospect. Wouldn’t it be great if there were a more real-time way of determining if an emerging technology was a GPT? Certainly such information would be valuable for business executives and policymakers. Making productive use of GPTs, economist Erik Byrnjolfsson has explained, requires organizations to “invest time and effort creating intangible assets like new business processes, new skills, new goods and new services.” This is why it can take years for a GPT to show up in productivity statistics. That was the case with the dynamo, the computer, and now AI.

Making that GPT evaluation is exactly the problem tackled by Avi Goldfarb (Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto), Bledi Taska (Emsi Burning Glass), and Florenta Teodoridis (University of Southern California) in their new NBER working paper “Could Machine Learning be a General Purpose Technology?: A Comparison of Emerging Technologies Using Data from Online Job Postings.” From that paper:

GPTs are different from other technologies. They hold potential for substantial economic impact, but the impact is not guaranteed. Economic actors need to engage in appropriate strategies that solve the canonical GPT problem; the large productivity gains from GPTs occur when there is a coordinated positive feedback loop in innovation between producing and application industries. … Furthermore, these processes take time, are costly, and the productivity benefits may require several years to appear. … It is then beneficial to have an early sense if a technology is GPT. When new technologies appear, it is not unusual to find claims that these technologies are general purpose. The speculations are generally informed by observed widespread engagement with the emerging technologies. Although this is just one characteristic of GPTs, the speculations emerge because a more comprehensive evaluation of GPT-ness is generally available with a lag, after the benefits of the technology have been realized.

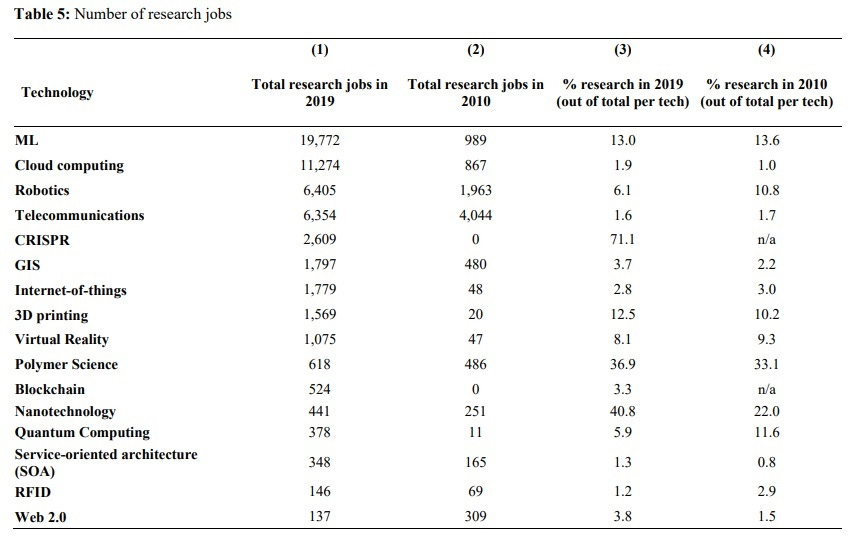

Basically, the researchers try to assess the GPT likelihood of emerging technologies by using data from some 200 million electronic job postings in the US from 2010 through 2019 collected by Burning Glass Technologies, a provider of real-time labor market data products and analysis. Goldfarb, Taska, and Teodoridis looked at all the technologies listed in the Gartner “hype cycle” list from 1995 to 2019 and identified the subset of technologies that are also listed as research skills in the Burning Glass job posting data for a total of 21 technologies.

Identifying pervasiveness is the goal here. The team determines to what extent over the past decade do various technologies appear in research job postings as measured by the number of research job postings “with skills that map onto the technology” and the fraction of such postings that are research-focused. They then they examine the sectoral breadth of the listings, according to government industrial classifications codes. (The researchers also benchmark their approach against prevailing GPT methods that use patent data, finding a strong correlation.) Their conclusion:

Our results suggest that a suite of data-focused technologies (BI, big data, data mining, data science, and [natural language processing])—often represented by [machine learning] —are relatively likely to be a GPT. Cloud computing and robotics also display some characteristics of GPTs. … Our results also show that several technologies are unlikely to be general purpose. For some of these technologies, this is unsurprising; both scholars and practitioners did not engage in speculations about the general purpose likelihood of these technologies. … For other technologies, the results suggest that some claims of technologies being general purpose seem unlikely in their current stage; notably for 3D printing, nanotechnology, IoT, and blockchain.

Sidenote: Tech analyst Benedict Evans gives one of favorite ML definition defintions/explanations: “Machine learning lets us find patterns or structures in data that are implicit and probabilistic (hence ‘inferred’) rather than explicit, that previously only people and not computers could find. They address a class of questions that were previously ‘hard for computers and easy for people’, or, perhaps more usefully, ‘hard for people to describe to computers.’”

Now just because a particular technology doesn’t currently qualify as a GPT doesn’t mean it’s a bust. So no angry comments, please, blockchain enthusiasts! As the researchers also note: “The application also does not capture technologies in very early stages. For example, quantum computing may someday become a GPT, given that it represents the next generation of computational devices, but the technology is not yet sufficiently developed.” And watching job postings is one way to see how that development is proceeding across the economy.

5QQ

❓❓❓❓❓ Five Quick Questions for … economist Jason Barr on making a bigger Big Apple

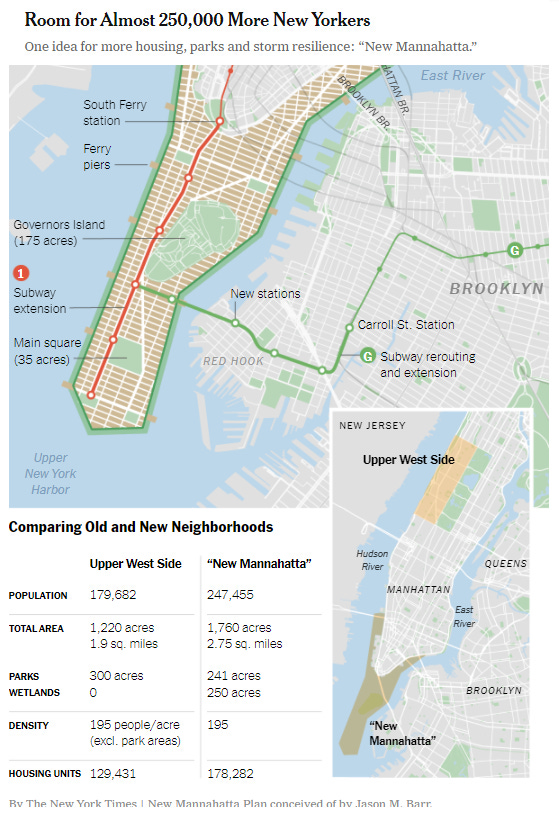

Jason M. Barr, a Rutgers University-Newark economist, is the author of Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers and The Skynomics Blog. He recently wrote a buzzy op-ed for The New York Times in which he proposed reshaping the southern part of the Manhattan shoreline by extending the island into New York Harbor by 1,760 acres — creating “New Mannahatta.” Barr: “This new proposal offers significant protection against surges while also creating new housing.” I had some question about the idea, which I asked him.

1/ You write that New York was once a city of big projects. What happened? Have we become more averse to building than we once were?

Yes, we have become more averse to big projects. Some of it comes from the fact that older cities in general are denser and it’s more disruptive and expensive to do things, as compared to when cities still had a lot of underdeveloped territory. However, we have erected political, legal, and bureaucratic barriers because of the mistakes of the last era of “big projects” after World War II. In New York, Robert Moses is still used as a boogeyman for why we are not allowed to think about big projects.

2/ Wouldn't reforming zoning restrictions be an easier fix to the housing shortage in New York?

My short answer is: perhaps. The zoning codes that New York City currently has were enacted in 1961. Since then, there’s been a lot of tinkering but no real reform. So, if we can’t reform the codes in six decades then what’s the chance that we could do that any time soon? You can see this today, Governor Hochul is proposing legalizing ADUs and the NIMBYists are fighting back.

Plus, just loosening the zoning rules may not fix the problem without policies related to reducing high construction and land acquisition costs and eliminating other hurdles preventing widescale housing construction (not to mention policies for improvements in the transportation infrastructure).

3/ Wouldn't this proposal put housing in a new flood-prone area to protect areas like the Financial District (where people don't live) from flooding?

[See #1] I would also add that the population of the of Lower Manhattan (CD101) is about 165,000. The area around Wall Street has some 60,000 residents. So there’s more than just a working daytime population. Plus, with office vacancies remaining high for the foreseeable future, and housing affordability remaining a problem, the resident population will likely increase as more office buildings are converted to residential.

4/ What do you say to the idea that just building wetlands would offer much better flood protection at a fraction of the cost?

This is probably true in a direct sense, but, if judicially executed, my plan allows the city to leverage its incredibly high real estate values for the greater good. Today, it’s reasonable to assume an average Manhattan real estate market price of $1500 per square foot and building construction costs at $500 square foot. This $1000 “profit” could more than pay for the cost of the new land and infrastructure and provide billions to the city coffers for more climate change mitigation and environmental improvements. Plus, the new real estate gets put on tax rolls, potentially adding billions for the city’s operating expenses.

5/ Expanding New York by infilling the rivers is an old idea that we've executed before. Why does it feel so pie in the sky and challenging today despite our technological advancements?

It feels pie-in-the-sky for two reasons. First, we remain unaware of how many other cities around the world are using infill to both protect their shorelines and expand their cities for badly needed housing and to improve the quality of urban life more broadly. Second, the infill projects of the past were done when there was little concern for the environment and the ecosystems. Decades of fighting to clean up the Hudson River estuary have meant that it has become, let’s say just, impolite, to suggest that we reconsider economic development in and around it. While I’m completely mindful of the environmental issues, we ultimately have to consider the big picture: how do we best help Gotham remain successful while also minimizing the unintended consequences.

⭐ Bonus: New York City struggles to expand the subway. What makes you think something like this could actually be built?

First, I think comparing the subway problem to my plan is a bit of an apples-to-oranges comparison. The subway system has its own history, its own bureaucratic problems, and is unable to be organized in way that generates sufficient revenue to allow it to expand (for a better model of mass transit profitability see Hong Kong). My plan would create a new development corporation and would have fewer of the historical burdens that plague the subway.

Having said that, my plan would face similar immense legal and bureaucratic challenges, which would ultimately doom it without widescale mass support. However, if judiciously executed, my proposal could generate enormous sums of income for the city to use for things like improving the subway, cleaning up the river, and mitigating against climate change.

Micro Reads

☀ For a Clean-Energy Future, We Need Deregulation - Ted Nordhaus, WSJ | One of the key theses of this newsletter is that there’s been a regulatory overcorrection in dealing with environmental problems of sorts. And that’s harmful for not just technological progress and economic growth, but also for the environment. Nordhaus writes, “Across the country, foundational laws established in the 1960s and ‘70s to protect the environment are today a major obstacle to efforts to build the infrastructure and energy systems that we need to safeguard public health and save the climate.” One of the many examples cited: “In Nevada’s Black Rock Desert, local environmentalists and devotees of the Burning Man festival are using the National Environmental Policy Act to oppose a geothermal energy plant.”

📈 Productivity and pay: A comparison of the US and Canada - Jacob Greenspon, Anna Stansbury, and Lawrence H. Summers, VoxEU | This study makes for a great companion piece to my recent essay, “The productivity-pay 'gap': a pernicious economic myth.” From the analysis: ‘Overall, our findings support the hypothesis that productivity growth still matters for middle-class income growth. Measures to boost productivity growth are important for raising pay for the average and typical worker – and conversely, a continued productivity slowdown will reduce the likelihood of increased real compensation.”

🎁 Gifted Children Programs’ Short and Long-Term Impact: Higher Education, Earnings, and the Knowledge-Economy - Victor Lavy and Yoav Goldstein, NBER | Too bad I didn’t have this study handy before my previous essay, “The War on Gifted Education.” This finding really pops out: “In the long-term, we find no effects of GCP on the rate students gain B.A. degrees, as almost all (98 percent) treated and comparison gifted children achieve this degree. Still, we find a positive and relatively large impact on graduating with a double major and gaining Ph.D. degrees (driven by an increase in Ph.D. degrees from Elite Universities). We also find that GCP affect the choice of field of study, increasing academic degrees in math, computer science, and physical sciences and sharply reducing degrees in engineering programs.”

Nano Reads

Against Meta - Michael Brendan Dougherty, NRO |

A radical new technique lets AI learn with practically no data - Karen Hao, MIT Tech Review |

Elon Musk's Boring Company has submitted a proposal for a 6.2-mile underground transit system in Miami - Kate Duffy, Business Insider |

The Making of a New Government-Funded Moonshot Model - Philip Aldrick, Bloomberg Businessweek |

The Elusive Hunt for a Robot That Can Pick a Ripe Strawberry - Khari Johnson, Wired |

Don’t Cede the Space Race to China and the Billionaires - Jess Sheshol, NYT |

Life on ‘Mars’: the strangers pretending to colonize the planet – in Utah - J. Oliver Conroy, Guardian |

Live Under the Sea? Not for Me. - Jason Gay, WSJ |

Electric Flying Cars Are Just Dirty Old Helicopters, Rebranded - David Fickling, Bloomberg |

Midwestern states want to become “hard-tech” hubs - The Economist |